A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, January 12, 2025

Ten Cents a Dance (Lionel Barrymore, 1931)

Cast: Barbara Stanwyck, Ricardo Cortez, Monroe Owsley, Sally Blane, Blanche Friderici, Phyllis Crane, Victor Potel, Al Hill, Jack Byron, Pat Harmon, Martha Sleeper, David Newell, Sidney Bracey. Screenplay: Jo Swerling, Dorothy Howell. Cinematography: Ernest Haller, Gilbert Warrenton. Art direction: Edward C. Jewell. Film editing: Arthur Huffsmith.

Saturday, December 28, 2024

Shopworn (Nick Grinde, 1932)

Wednesday, December 11, 2024

Forbidden (Frank Capra, 1932)

|

| Adolphe Menjou and Barbara Stanwyck in Forbidden |

Cast: Barbara Stanwyck, Adolphe Menjou, Ralph Bellamy, Dorothy Peterson, Thomas Jefferson, Myrna Fresholt, Charlotte Henry, Oliver Eckhardt. Screenplay: Frank Capra, Jo Swerling. Cinematography: Joseph Walker. Film editing: Maurice Wright.

If you can bring yourself to believe that Barbara Stanwyck's character would spend her life devoted to Adolphe Menjou's, you might like Forbidden. Its writer and director, Frank Capra, didn't, almost apologizing for it in his memoirs. Menjou was a fine character actor with a film career that stretched from 1916 to 1960, but he was no leading man. He was the guy you called on for suave but starchy, not for a lifetime of illicit passion. In Forbidden he's a lawyer and aspiring politician who meets Stanwyck's Lulu on a cruise to Havana. She's a librarian longing for romance, so she spends all her savings on that fateful cruise. They meet cute, of course: He's a little drunk and somehow mistakes her room, No. 66, for his, No. 99. Unfortunately, he's married (she doesn't know this till later) and unwilling to divorce his wife because she was seriously injured in an automobile accident he caused. But they keep seeing each other after they return to the States, she gets pregnant, and through a preposterous series of events winds up letting him and his wife adopt the child she gives birth to. Meanwhile, his political career takes off, although he has made an enemy of a newspaper editor (Ralph Bellamy), who just happens to be Lulu's boss and who wants to marry her. This elaborate contraption of a plot creaks and groans its way to a denouement that's as improbable as the rest of ir. If anything redeems the movie, it's Stanwyck's professionalism, her commitment to creating a character that's almost credible while you're watching her, but really doesn't when you think about it afterward. Capra also directs as if his story makes sense, which is no small feat.

Tuesday, December 10, 2024

Ladies of Leisure (Frank Capra, 1930)

.jpg) |

| Ralph Graves and Barbara Stanwyck in Ladies of Leisure |

Thursday, April 25, 2024

The File on Thelma Jordon (Robert Siodmak, 1950)

|

| Wendell Corey and Barbara Stanwyck in The File on Thelma Jordon |

Cast: Barbara Stanwyck, Wendell Corey, Paul Kelly, Joan Tetzel, Stanley Willis, Richard Rober, Minor Watson, Barry Kelley, Gertrude Hoffman. Screenplay: Ketti Frings, Marty Holland. Cinematography: George Barnes. Art direction: Hans Dreier, A. Earl Hedrick. Film editing: Warren Low. Music: Victor Young.

The chief problem with The File on Thelma Jordon is casting. Barbara Stanwyck's performance is terrific, of course, Robert Siodmak keeps a complex plot from snarling, and George Barnes's lights and shadows are eloquent. But Stanwyck is paired once again with Wendell Corey, who was her ineffective leading man in Anthony Mann's otherwise splendid The Furies, also made in 1950. Corey has no charisma and no depth. The screenplay may be at fault in not letting us see why Cleve Marshall's antagonism to his father-in-law is driving him to drink -- and into the arms of Stanwyck's scheming Thelma Jordon -- but Corey's hangdog manner doesn't help. Nor does he bring much visible intelligence to Marshall's scheming to undermine his own defense of Thelma when she's brought to trial for killing her aunt -- a murder he helped her cover up. The ending is also a bit of a muddle, largely because the Production Code meant that Thelma's crime had to be punished. What could have been a classic film noir ends up only a passable one.

Monday, February 26, 2024

The Bitter Tea of General Yen (Frank Capra, 1932)

|

| Nils Asther and Barbara Stanwyck in The Bitter Tea of General Yen |

Maybe the best way to approach a movie like The Bitter Tea of General Yen today is to think of it as science fiction: a story taking place on a distant planet called t'Chaï-nah. Think of the heroine, Megan Davis (Barbara Stanwyck) as coming from Earth to a planet torn by civil war, seeking out her fiancé, an astronaut tasked with bringing a message of peace. Captured by the forces supporting General Yen (Nils Asther), she discovers all manner of intrigue involving the beautiful Mah-Li (Toshia Mori), one of the general's servants, and Mah-Li's lover, Captain Li (Richard Loo), as well as some exploitative dealing by her fellow Earthling, a man named Jones (Walter Connolly), the general's financial adviser. Megan finds herself strangely drawn to the alien general, despite the prohibition against interplanetary sexual relations. That way we might be able to set aside our objections to the ethnic stereotypes, the yellowface makeup of the Swedish actor playing the title role, the chop suey chinoiserie of its design and costumes, and the nonsensical taboo against "miscegenation." Because Frank Capra's film has a core of good sense and solid drama to it that almost, but not quite, overcomes the routinely racist attitudes of the time when it was made. It has good performances by its leads, some lively action scenes, and a leavening of sardonic humor provided by Connolly's Jones, who admits that he's "what's known in the dime novels as a renegade. And a darn good one at that." It also demonstrates that Capra was a pretty good director when he wasn't indulging in the sentimental populism that his most famous movies bog down in.

Monday, June 8, 2020

Baby Face (Alfred E. Green, 1933)

|

| Theresa Harris and Barbara Stanwyck in Baby Face |

Baby Face has a reputation as the raunchy film that helped bring about the stifling Production Code in 1934, the year after it was released. But even in its original version -- for years only the expurgated film could be seen -- it doesn't exhibit much that would bring a blush to today's maiden cheeks. To be sure, its heroine, Lily Powers (Barbara Stanwyck), sleeps around in her determination to get somewhere, which in her case is marriage to a bank president. But this moral deviance, the film suggests, is the result of having been pimped out by her bootlegger father from the age of 14. So when he's blown up by the explosion of one of his stills, what else can she do but head for the big city and try to better herself? She has, after all, only the guidance of a middle-aged German, a customer of her father's speakeasy, who quotes Nietzsche at her. Her will to power involves the only capital she has: her body. So she sleeps her way up the flowchart of a New York bank until she's the kept woman of a vice-president, and when that ends in his being murdered by an ex-lover who also commits suicide in what the newspapers call a "love nest," she gets paid off -- to prevent her selling her diary to the newspapers -- with a job at the bank's Paris branch. And then she goes straight, fending off the attentions of various men, and making a success of the bank's travel bureau division. It can't end there, however, because when the bank's young president, Courtland Trenholme (George Brent), comes to Paris on a visit, they fall in love and get married, causing a scandal that leads to the bank's closing and Trenholme's indictment for some kind of corporate malfeasance. When he asks Lily to help him out financially -- she has accumulated half a million dollars in gifts from him, and presumably from her former lover -- she refuses, reverting to the ruthless, hard-edged Lily. But just as she's about to leave him she has a change of heart, only to find that the desperate Trenholme has tried to commit suicide. He's not mortally wounded, however, and in the ambulance on the way to the hospital she confesses that she really loves him and he gazes gratefully at her. Fade out. Censors in states like New York bridled at the apparent rewarding of sin and forced Warner Bros. to cut some of the more scandalous scenes and to change the ending so that Lily does penance by returning to her old home town to live a chastened life. But even in its long-lost uncensored version, there's something a little off about Baby Face, a feeling that it wants to be more than just a story about sex and upward mobility. The men in the film, including the young John Wayne, are an unmemorable series of himbos and sugar daddies, easy pushovers for the likes of an ambitious and unscrupulous young woman. The last-minute change of heart and the squishy happy ending feel unearned. What coherence the film has comes not from the script but from Barbara Stanwyck's performance, from her tough likability.

Sunday, April 5, 2020

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (Lewis Milestone, 1946)

|

| Lizabeth Scott, Barbara Stanwyck, and Van Heflin in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers |

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers doubles up on Lorenz Hart's line about "the double-crossing of a pair of heels" to give us a quartet of duplicity. There are no really good guys in the movie, though it tries to persuade us that tough guy Sam Masterson (Van Heflin) and lost girl Toni Marachek (Lizabeth Scott) are more to be admired than ruthless Martha Ivers O'Neil (Barbara Stanwyck) and her weakling alcoholic husband, Walter (Kirk Douglas). After all, teenage Martha (Janis Wilson) did kill her imperious aunt (Judith Anderson) and, with the connivance of young Walter (Mickey Kuhn) and his father (Roman Bohnen), not only cover up the murder but also frame someone else for the job. So when Sam returns to Iverstown after 18 years, Martha and Walter naturally think that he witnessed the murder and is there to blackmail them. Actually, young Sam (Darryl Hickman) beat it out the door before the aunt was conked on the head and fell downstairs, so he's ignorant -- until well into the film -- of their crime. It's not exactly clear why Sam, who makes a living by gambling, has drifted back in town, but he's not there long before he hooks up with Toni, fresh out of prison for a theft she didn't really commit, and the two of them get dragged unwittingly into the machinations of Martha and Walter. The movie was Douglas's film debut, so he receives fourth billing after Scott. He feels a little miscast as the manipulated Walter. For one thing, he was nine years younger than Stanwyck, but he also had, even then, a stronger hold on the screen than Heflin. This is, I think, a movie that doesn't have the courage of its own nastiness, trying to make us think that Sam and Toni really deserve a happy ending when it's more likely that they will eat each other alive. Trivia note: The sailor in the car with Sam when he has his accident is played by future writer-producer-director Blake Edwards.

Friday, April 3, 2020

Executive Suite (Robert Wise, 1954)

|

| William Holden and June Allyson in Executive Suite |

It has been called "Grand Hotel in the boardroom" more than a few times, because what it has in common with Edmund Goulding's 1932 best picture winner is that it was made by MGM and features an all-star cast. Executive Suite doesn't have much else in common with the earlier film, which was an entertaining stew of intrigue among the glamorous guests of a Berlin hotel. This is a story about power plays in a Pennsylvania furniture manufacturing company, which is about as glamorous as it sounds. The company's president has died without leaving a designated successor. We even see him die -- or rather, we die with him, as the film opens with a subjective camera as Avery Bullard leaves his Manhattan office to take a plane to Pennsylvania for a meeting with his vice-presidents. Through his eyes we see employees greet him as he leaves his office, the elevator doors closing on him, and finally the sidewalk as he collapses from a stroke. A passerby filches the wallet he drops, empties it of cash, and tosses it in a trashcan, thereby postponing the identification of his body. So much for any real action in the movie: The rest is talk, as the company's vice-presidents gather for the meeting and then gradually learn of his death. But one person knew of Bullard's death before them: George Caswell (Louis Calhern), a member of the company's board of directors who from his office window saw Bullard's body taken away by an ambulance and now uses this knowledge to try to pull a fast one with the company's stock. Eventually, there will be a struggle among the vice-presidents to take over Bullard's job as president. It will pit Loren Shaw (Fredric March), the bean-counting company controller, against Don Walling (William Holden), the v.p. for development who is excited about a new manufacturing technique he and his staff have been working on. And that's about as dramatic as it sounds. We all know that Walling will triumph over Shaw, probably because Walling has a nice, faithful wife played by June Allyson and a son who plays Little League baseball, and Shaw doesn't. It looks for a long time like Shaw will win, partly because he is in cahoots with Caswell, promising to make his stock deal work in exchange for his vote. Walling has to win over the other members of the board, who include old-timer Fred Alderson (Walter Pidgeon), who is on his side from the start; Walter Dudley (Paul Douglas), the v.p. for sales who is carrying on an affair with his secretary (Shelley Winters), making him susceptible to blackmail by Shaw; and most crucially of all, the daughter of the company's founder, Julia Tredway (Barbara Stanwyck), who had been involved in a frustrating love affair with Bullard and now threatens to dump her stock in the company. In the end, Walling triumphs with a big speech about the company's ideals and how they're being undermined by Shaw's insistence that the only thing that matters is the stockholders' return on investment, which has led to the construction of cheap and shoddy products. It's a sentimental fable about the "good capitalist" that mercifully doesn't indulge in the red-baiting that might have been expected in a film of the 1950s but ultimately rings false. Ernest Lehman's screenplay does what it can with Cameron Hawley's novel, Robert Wise directs as if it were a better film than it is, and Nina Foch won an Oscar for her role as the company's capable executive secretary, the only woman in the film who isn't completely under the thumb of the men. A trivia note: The narrator and the off-screen voice of Tredway is future NBC newman Chet Huntley.

Wednesday, October 9, 2019

Gambling Lady (Archie Mayo, 1934)

Gambling Lady (Archie Mayo, 1934)

Cast: Barbara Stanwyck, Joel McCrea, Pat O'Brien, C. Aubrey Smith, Claire Dodd, Robert Barrat, Arthur Vinton, Phillip Reed, Philip Faversham, Robert Elliott, Ferdinand Gottschalk, Willard Robertson, Huey White. Screenplay: Ralph Block, Doris Malloy. Cinematography: George Barnes. Art direction: Anton Grot. Film editing: Harold McLernon. Music: Bernhard Kaun. Costume design: Orry-Kelly.

Barbara Stanwyck is invariably the best reason to watch any of her movies, and never more so than in Gambling Lady. Oh, her supporting cast is just fine: Joel McCrea is her reliable leading man and Claire Dodd makes the most of her rich-bitch foe. And the story, though familiar enough in its outlines and predictable enough in its resolution, keeps your attention, partly because the Production Code hadn't yet put a choke hold on depictions of the seamier side of life. Stanwyck plays Jennifer "Lady" Lee, an honest woman in a shady milieu: She's a professional gambler who refuses to cheat. It's a familiar Stanwyck character: tough but vulnerable, and she gets many chances to show both sides throughout the film. Her best moment, perhaps, comes at the film's climax, when the rich bitch triumphs, forcing Lady to lie to save McCrea's character, the wealthy Garry Madison, whom Lady has married, from jail. So we get Stanwyck putting on a façade of cynical laughter as she pretends she has never really loved Madison but was just in it for the money. We who know the truth can see the tears welling up inside Lady, but Stanwyck successfully keeps up the front before she makes her exit and collapses in grief. This is screen acting at its best, so that even if the plotting is contrived and the situation trite, Stanwyck wins us over, making more of the scene, in fact of the whole movie, than it really deserves.

Sunday, June 23, 2019

The Mad Miss Manton (Leigh Jason, 1938)

|

| Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda in The Mad Miss Manton |

If The Mad Miss Manton seems to me a laborious misfire of a screwball comedy, it may be because I can't help comparing it to another film that also stars Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda, Preston Sturges's sublime The Lady Eve (1941). Stanwyck plays the doyenne of a gaggle of silly socialites who get involved in trying to solve a murder. They tangle with a police lieutenant played by Sam Levene and a reporter played by Fonda in the process, but Stanwyck's character and Fonda's naturally fall in love during the proceedings. It's over-frantic and under-motivated.

Monday, November 19, 2018

Clash by Night (Fritz Lang, 1952)

|

| Robert Ryan and Barbara Stanwyck in Clash by Night |

Jerry D'Amato: Paul Douglas

Earl Pfeiffer: Robert Ryan

Peggy: Marilyn Monroe

Joe Doyle: Keith Andes

Uncle Vince: J. Carrol Naish

Papa D'Amato: Silvio Minciotti

Director: Fritz Lang

Screenplay: Alfred Hayes

Based on a play by Clifford Odets

Cinematography: Nicholas Musuraca

Art direction: Carroll Clark, Albert S. D'Agostino

Film editing: George Amy

Music: Roy Webb

There's a wonderful directorial touch in the middle of Fritz Lang's Clash by Night that almost makes up for the talky melodrama of the rest of the film: Stealing from the romantic gesture executed by Paul Henreid in Now, Voyager (Irving Rapper, 1942), Lang has Robert Ryan light two cigarettes at once and hand one of them to Barbara Stanwyck. She looks at it with distaste for a moment, then tosses it over her shoulder, takes out her own pack of cigarettes, and lights one herself. It's possible that the moment is spelled out in Alfred Hayes's screenplay, or in the play by Clifford Odets on which it's based, but I like to think of it as Lang's own employment of Stanwyck's great gift for playing women in charge. In fact, Stanwyck's character, Mae Doyle, is hardly ever fully in charge -- she can't control her life because of the men in it, which she describes as either "all little and nervous like sparrows or big and worried like sick bears." The problem with Clash by Night is not the cast, which is uniformly watchable, or the direction, which does what it can with the material, particularly by exploiting the film's setting -- Monterey, the bay, the fishing fleet, and Cannery Row -- but the screenplay. It's full of Odets characters who can't resolve their internal conflicts but also can't stop talking about them. Even the secondary characters, like Jerry D'Amato's father and uncle, can't help putting in their two cents, often in florid Odetsian metaphor. The title of the film comes from Matthew Arnold's "Dover Beach," in which the speaker laments the loss of faith in a world that has "neither joy, nor love, nor light, / Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain." It's a place where "ignorant armies clash by night." That bleak Victorian pessimism, however, doesn't translate very well to a story in which the clashing armies are men and women, a battle of the sexes that's a little too conventional in concept. Mae returns to her family home in Monterey, and immediately starts making a mess of things by attracting not only the good-hearted Jerry but also his cynical burnt-out friend Earl. Since Jerry is played by the somewhat schlubby Paul Douglas and Earl by the handsome Robert Ryan, we can see immediately where this is going to go, and the wait for it to get there gets a little tedious. There's also a rather pointless secondary plot involving Mae's brother, Joe, and his girlfriend, Peggy, who are played by Keith Andes and Marilyn Monroe. The backstories that stars and their personae bring to the roles they play are often valuable. Here, however, Marilyn's presence in the cast has unbalanced our subsequent reaction to the film, which can never be watched without the irrelevant knowledge of the actress's skyrocketing career, troubled relationship with her directors (including Lang, who terrified her so much that she vomited before performing a scene), and pitiable demise. Peggy is a small role, and she plays it well, but it was never meant to be the principal reason many people watch Clash by Night.

Thursday, September 20, 2018

Stella Dallas (King Vidor, 1937)

|

| Barbara O'Neil and Barbara Stanwyck in Stella Dallas |

Stephen Dallas: John Boles

Laurel Dallas: Anne Shirley

Helen Morrison: Barbara O'Neil

Ed Munn: Alan Hale

Mrs. Martin: Marjorie Main

Charlie Martin: George Walcott

Miss Phillibrown: Ann Shoemaker

Richard Grosvenor: Tim Holt

Director: King Vidor

Screenplay: Sarah Y. Mason, Victor Heerman

Based on a novel by Olive Higgins Prouty and its dramatization by Harry Wagstaff Gribble and Gertrude Purcell

Cinematography: Rudolph Maté

Art direction: Richard Day

Film editing: Sherman Todd

Costume design: Omar Kiam

Music: Alfred Newman

I'm bothered by an inconsistency in the title character of King Vidor's Stella Dallas. When Stella's estranged husband, Stephen, shows up unexpectedly at Christmastime bearing gifts for her and their daughter, Laurel, Stella makes a determined effort to look "respectable": She rummages through her closet, rejecting all the flowery, overtrimmed dresses she usually favors, and chooses a black dress, removing most of its trimmings, and even goes so far as to wipe off the lipstick she has just applied. But later, when she takes Laurel to a snooty resort, she's a blowsy horror again, swaggering vulgarly through the amused upperclass crowd -- and thereby precipitating the final separation between her and Laurel. What happened to the self-aware Stella who knew how to present herself as a suitable mate for Stephen Dallas? But the thing about this inconsistency, and other little melodramatic clichés that infest the film, is that it doesn't matter: Stella Dallas triumphs because Barbara Stanwyck believes in her and because King Vidor knows how to manipulate our responses to the characters. Stella's appearance at the resort is played as simultaneously comic -- who doesn't laugh at the way she's dressed, swanning around with a white fox fur? -- and tragic -- Stella's insistence on being herself is her fatal flaw. Similarly, when Ed Munn shows up drunk, wagging around a large turkey he has brought for Stella and Laurel's Christmas and stuffing it head, feet, and all into the oven, the scene is hilarious -- Alan Hale is wonderful here -- until it isn't, until we realize the damage it is going to do to Stella and her daughter. And the celebrated final scene, of Stella watching Laurel's wedding through the window, is beautifully performed by Stanwyck, chewing on her handkerchief, and magisterially staged by Vidor. Tears are flowing in the audience as Stella strides across the street, but she's beaming, having accomplished her chief goal: to see Laurel happy. Critiques of the movie's treatment of maternal self-sacrifice, or of marriage as the consummation of a woman's happiness, are many and cogent. But let's just take a moment to reflect on the skill with which these ideas and attitudes, retrograde as we may find them, have been presented on film.

Friday, May 25, 2018

Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks, 1941)

|

| Henry Travers, Aubrey Mather, Oskar Homolka, Leonid Kinskey, Gary Cooper, S.Z. Sakall, Tully Marshall, Barbara Stanwyck, and Richard Haydn in Ball of Fire |

Sugarpuss O'Shea: Barbara Stanwyck

Prof. Oddly: Richard Haydn

Prof. Gurkakoff: Oskar Homolka

Prof. Jerome: Henry Travers

Prof. Magenbruch: S.Z. Sakall

Prof. Robinson: Tully Marshall

Prof. Quintana: Leonid Kinskey

Prof. Peagram: Aubrey Mather

Joe Lilac: Dana Andrews

Garbage Man: Allen Jenkins

Duke Pastrami: Dan Duryea

Asthma Anderson: Ralph Peters

Miss Bragg: Kathleen Howard

Miss Totten: Mary Field

Larsen: Charles Lane

Waiter: Elisha Cook Jr.

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder, Thomas Monroe

Cinematography: Gregg Toland

Art direction: Perry Ferguson

Film editing: Daniel Mandell

Music: Alfred Newman

If this intersection of the talents of Billy Wilder and Howard Hawks doesn't feel much like a typical film from either, lacking some of Wilder's acerbity and Hawks's ebullience, it's perhaps because it was made under the watchful eye of producer Samuel Goldwyn. In fact, it's surprising to find Hawks working for Goldwyn at all after the brouhaha over Come and Get It (1936) that led to Hawks's being fired and replaced with William Wyler. But Goldwyn wanted the writing team of Wilder and Charles Brackett to work for him, and Wilder wanted to work with Hawks. Like everyone else in Hollywood, Wilder wanted to direct, and he wound up shadowing Hawks on the set of Ball of Fire, learning from the best. Wilder later called the picture "silly," and so it is -- not that there's anything wrong with that: Some of the greatest pictures both Wilder and Hawks made were silly, viz. Some Like It Hot (Wilder, 1959) and Bringing Up Baby (Hawks, 1938). Ball of Fire never quite reaches the heights of either of those movies, partly because it's encumbered by plot and cast. The "seven dwarfs" of Ball of Fire are all marvelous character actors, but there are too many of them so the film sometimes feels overbusy. The gangster plot feels cooked-up, which it is. The musical numbers featuring Gene Krupa and his orchestra bring the movie to a standstill -- a pleasant one, but it saps some of the momentum of the comedy. Still, Barbara Stanwyck is dazzling as Sugarpuss O'Shea, performing a comic twofer in 1941 with her appearance in Preston Sturges's The Lady Eve, in which she enthralls Henry Fonda's character as efficiently as she does Gary Cooper's in Ball of Fire. There are those who think Cooper is miscast, but I think he's brilliant -- he knows the role is nonsense but he gives it his all.

Sunday, August 14, 2016

The Lady Eve (Preston Sturges, 1941)

Monday, February 1, 2016

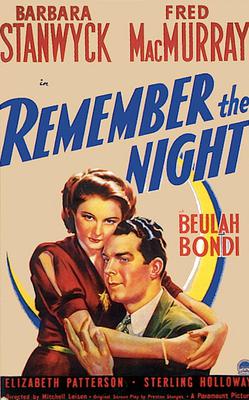

Remember the Night (Mitchell Leisen, 1940)

Sunday, January 31, 2016

Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Meet John Doe (Frank Capra, 1941)

|

| Walter Brennan, Gary Cooper, Irving Bacon, Barbara Stanwyck, and James Gleason in Meet John Doe |

Ann Mitchell: Barbara Stanwyck

D.B. Norton: Edward Arnold

The "Colonel": Walter Brennan

Mrs. Mitchell: Spring Byington

Henry Connell: James Gleason

Mayor Lovett: Gene Lockhart

Ted Sheldon: Rod LaRocque

Beany: Irving Bacon

Bert: Regis Toomey

Director: Frank Capra

Screenplay: Robert Riskin

Based on a story by Richard Connell and Robert Presnell Sr.

Cinematography: George Barnes

Art direction: Stephen Goosson

Film editing: Daniel Mandell

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Meet John Doe opens with reporters and editors at a newspaper being fired because the owner wants it to be, as the paper's new slogan says, "streamlined ... for a streamlined age." And the plot involves a very wealthy man who uses a phony populist approach to try to get himself elected president. Who says a 74-year-old movie isn't relevant today? But the movie eventually falls apart because Frank Capra can't get his story to make sense. I never watch a Capra film without wanting to throw something at the screen, and that includes the beloved It's a Wonderful Life (1946), which makes me faintly nauseated. Meet John Doe has a few wonderful things going for it, principally the opportunity to see Barbara Stanwyck and Gary Cooper at their starry prime. (Though they were much better in a movie they made together in the same year, Howard Hawks's Ball of Fire.) Experience tells, and by 1941 Stanwyck had been making movies for more than a decade, and Cooper had been in films since the mid-1920s. They had the kind of easy, spontaneous, natural manner on screen that could steady even the most wobbly vehicle. Meet John Doe starts to wobble about halfway through, when it becomes apparent that there is no easy way Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin can resolve the director's muddled populist sentiments: Capra always wants to celebrate the "common man" in his movies, but it was clear to anyone on the brink of the entry of the United States into World War II that the common man was a dangerous force to work with. So what we have in the film is an odd mix of sentimentality and cynicism. Stanwyck's character, Ann Mitchell, starts as a cynic, concocting a sob story about a "John Doe" who threatens to commit suicide because he's fed up with a corrupt society. She does it to save her job at the newspaper, and the equally cynical managing editor Henry Connell decides to run with it. That's when they find a homeless man (Cooper) to pretend to be the real John Doe. When he turns out to be an inspiration to the "common man" of Capra's fantasies, bringing about peace and harmony across the land, the sentimentality takes over, converting Ann and Connell, but also playing into the hands of the paper's owner, D.B. Norton, who tries to use John Doe's followers for political gain. And when John Doe is exposed as a fake, the adoring millions suddenly turn into a raging mob. If Capra weren't so invested in making things turn out all right, he could have created a powerful satire, but he couldn't find an ending to the film that would satisfy both his Hollywood-nurtured sentimentality and the logic of the plot.