|

| Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell in Macao |

Cast: Robert Mitchum, Jane Russell, William Bendix, Thomas Gomez, Gloria Grahame, Brad Dexter, Edward Ashley, Philip Ahn, Vladimir Sokoloff, Don Zelaya.

Screenplay: Bernard C. Schoenfeld, Stanley Rubin, Robert Creighton Williams.

Cinematography: Harry J. Wild.

Art direction: Ralph Berger, Albert S. D'Agostino.

Film editing: Samuel E. Beetley, Robert Golden.

Music: Anthony Collins.

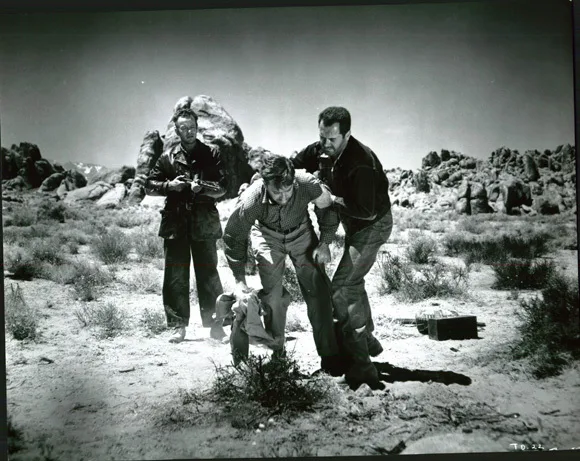

Macao has the makings of a much better movie: two enormously potent and well-matched stars, a solid supporting cast, a legendary director, an exotic setting, and a twisty, noirish plot. What it doesn't have is dialogue worthy of speaking. The actors give the right twists to their lines, but too often they fall flat. "You don't want that junk," Brad Dexter's Halloran says to his mistress, Margie (Gloria Grahame), about the jewel she's flashing. "Diamonds would only cheapen you." "Yeah," she replies, "but what a way to be cheapened." At another point, Robert Mitchum's Nick Cochran tells Margie, "You know, you remind me of an old Egyptian girlfriend of mine: the Sphinx." She retorts, "Are you partial to females made of stone?" This is tin-eared repartee at best, delivered by the actors as if they were the witty work of better screenwriters like Jules Furthman or Ben Hecht. Still, the opportunity to see Mitchum paired with Jane Russell, one of the few actresses capable of putting him in his place, is irresistible. She plays Julie Benson, an itinerant night club singer who meets Cochran on board the ship on which they're making their way from Hong Kong to Macao. He's a soldier of fortune, on the lam from some sort of misdeed in New York. She picks his pocket, keeps the dough, and tosses his wallet, which contains his passport, overboard. They cross paths again in Macao, where she goes to work for club owner Halloran, who has his own problems with the police. He knows that a detective is coming to Macao to try to nab him, and when Cochran shows up to try to get his money back from Julie, Halloran mistakes him for the detective. In fact, the detective turns out to be in disguise as a traveling salesman called Lawrence C. Trumble (William Bendix), whom Julie and Cochran met earlier on the ship. What follows is much ado about a diamond necklace that Halloran left in a safe deposit box in Hong Kong which Trumble is using to try to lure Halloran across the three-mile limit outside Macao so the police can arrest him. Some double-crosses and chase scenes and a few murders ensue before Cochran and Julie can embrace in the final scene. There's enough good stuff to overcome the misfired dialogue, despite the film's reputation as a troubled shoot in which the actors fought constantly with Sternberg, then at the end of his career. Nicholas Ray completed the film after Sternberg left the shoot, which started in 1950 -- RKO owner Howard Hughes held it from release as he tried to build Russell's career, which he had launched with hype and controversy over

The Outlaw (1943). The delay also explains why Gloria Grahame feels miscast in such a small role in

Macao: Her career had taken off while the film was on the shelf.