A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Benicio Del Toro. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Benicio Del Toro. Show all posts

Friday, September 27, 2019

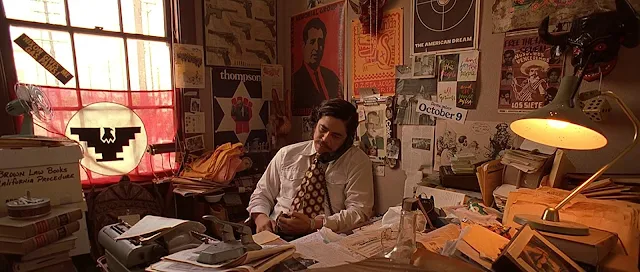

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Terry Gilliam, 1998)

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Terry Gilliam, 1998)

Cast: Johnny Depp, Benicio Del Toro, Tobey Maguire, Katherine Helmond, Craig Bierko, Mark Harmon, Laraine Newman, Verne Troyer, Penn Jillette, Cameron Diaz, Lyle Lovett, Flea, Gregory Itzin, Gary Busey, Christopher Meloni, Christina Ricci, Michael Jeter, Harry Dean Stanton, Ellen Barkin. Screenplay: Terry Gilliam, Tony Grisoni, Todd Davies, Alex Cox, based on a book by Hunter S. Thompson. Cinematography: Nicola Pecorini. Production design: Alex McDowell. Film editing: Lesley Walker. Music: Ray Cooper.

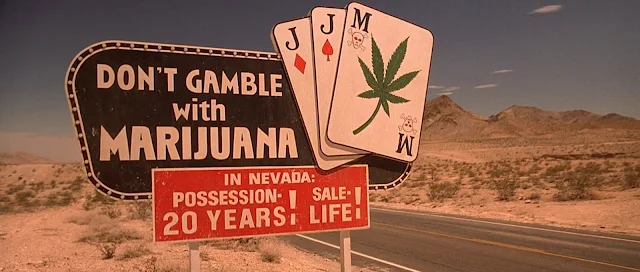

Terry Gilliam's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas invites the easy critical brush-off: What happened in Vegas should have stayed in Vegas. Many of its first-release critics, including Roger Ebert, certainly took that view. So did ticket-buyers, who stayed away. And even in hindsight it's a little hard to figure why the film was made when it was made. Hunter S. Thompson's book was published in 1971, and although there had been some earlier efforts to turn it into a movie, it was hardly fresh subject matter in 1998. But the film has developed followers over the years since, and it's now possible to appreciate the skill with which Gilliam takes on this recreation of a drug-maddened milieu, and especially the acting of Johnny Depp and Benicio Del Toro as the wildly tripping Duke and Dr. Gonzo. I will admit that Depp, 35 at the time, seems to me a little too young and fresh-faced for the dissipated Duke -- even though Thompson himself was pretty much the same age when the events he wrote about took place -- but it's one of his best performances. The film also benefits from an abundance of familiar faces in small roles, such as the underappreciated Ellen Barkin as a waitress unwilling to put up with abusive stoners. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas probably has little value except as a portrait of the Nixon era as seen from the end of the Clinton era, and it's certainly an exhausting film to watch, but it's a unique experience.

Saturday, July 27, 2019

Che: Part Two (Steven Soderbergh, 2008)

|

| Benicio Del Toro in Che: Part Two |

The continuation of Steven Soderbergh's epic portrait of Ernesto "Che" Guevara almost stands on its own as a film, focused as it is on Che's ill-fated attempt to stir revolution in Bolivia after the success in Cuba. Che: Part Two is subtitled "Guerrilla," and it deals largely with Che's illness -- he suffers from asthma -- and inability to control his troops before his final capture and execution. Soderbergh avoids an elegiac tone, concentrating instead on the details of guerrilla warfare.

Thursday, July 25, 2019

Che: Part One (Steven Soderbergh, 2008)

|

| Benicio Del Toro and Demián Bichir in Che: Part One |

Subtitled "The Argentine," the first part of Steven Soderbergh's epic portrait of Ernesto "Che" Guevara (Benicio Del Toro) covers the revolutionary's life from his first meeting with Fidel Castro (Demián Bichir) in 1955 through the success of the campaign in Cuba to Che's address to the United Nations in 1964, proclaiming a "battle to the death" against American imperialism. With a less coherent narrative line than the one in Che: Part Two, the first film feels more scattered and just a little superficial, but it has a strong feeling of actuality in any given sequence.

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

21 Grams (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2003)

|

| Melissa Leo and Benicio Del Toro in 21 Grams |

Cristina Peck: Naomi Watts

Jack Jordan: Benicio Del Toro

Mary Rivers: Charlotte Gainsbourg

Michael: Danny Huston

Marianne Jordan: Melissa Leo

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Screenplay: Guillermo Arriaga

Cinematography: Rodrigo Prieto

Music: Gustavo Santaolalla

An egg is an egg no matter how you scramble it. You can whip it into a meringue or a soufflé or an omelet, but it still retains its eggness. The same thing, I think, is true of melodrama: There's no disguising its improbabilities and coincidences, its short cuts around motive and characterization, its intent to surprise and shock. Mind you, I don't have anything against melodrama. Some of my favorite films are melodramas, just as some of our greatest plays, even some of Shakespeare's tragedies, are grounded on melodrama. It's just that you have to approach it without pretension, which is, I think, the chief failing of Alejandro González Iñárritu's 21 Grams. The melodramatic premise is this: The recipient of a heart transplant falls in love with the donor's widow, who then persuades him to try to kill the man who killed her husband. It's the stuff of which film noir was made, but Iñárritu takes screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga's premise and scrambles it, using non-linear narrative devices -- flashbacks and flashforwards -- and casting an unrelievedly dark tone over it, as well as reinforcing a pseudoscientific message in the title, which is explicated at the end of the film. In 1907, a Massachusetts physician named Duncan MacDougall tried to weigh the human soul: He devised a sort of death-bed scales, which would register any loss of weight at the moment a patient died, thereby demonstrating to his satisfaction -- if not to the medical and scientific communities -- that the weight of the soul was approximately three-quarters of an ounce, or 21 grams. I suspect that Arriaga and Iñárritu meant the allusion to this bit of nonsense metaphorically, but it doesn't come off that way. By the end of the film, we are so weighed down with the misery of its protagonists that it feels like sheer bathos. This is not to say that 21 Grams is a total loss as a film. Iñarritu is one of our most celebrated contemporary directors, with back-to-back Oscars for Birdman (2014) and The Revenant (2015) to prove it. I just don't think he's found himself yet, but has become too caught up in narrative gimmicks that prevent him from delivering a completely satisfying film. There is much in 21 Grams to admire: The performances of Sean Penn, Naomi Watts, Benicio Del Toro, and Melissa Leo are as fine as their reputations suggest they would be. The narrative tricks are done with great skill, especially with the aid of cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, who uses color to make each of the narrative segments distinct from the others, so that when the film cuts from one to another, the viewer feels better oriented. And there's no denying the emotional impact of the film as a whole. It could hardly be otherwise, given the pain suffered by the protagonists: Cristina, who lost her husband and her two little girls; Jack, the ex-con who accidentally killed them and believes that it was all because Jesus wanted it to happen; and Paul, who finds his chance at a new life marred by knowledge that it was at the expense of other people's happiness. But in the end, all of this suffering is off-loaded onto us without any compensatory feeling of having been enlightened by it.

Monday, September 26, 2016

Sicario (Denis Villeneuve, 2015)

|

| Benicio Del Toro and Emily Blunt in Sicario |

Alejandro: Benicio Del Toro

Matt Graver: Josh Brolin

Dave Jennings: Victor Garber

Ted: Jon Bernthal

Reggie Wayne: Daniel Kaluuya

Steve Foring: Jeffrey Donovan

Manuel Diaz: Bernardo Saracino

Silvio: Maximiliano Hernández

Director: Denis Villeneuve

Screenplay: Taylor Sheridan

Cinematography: Roger Deakins

Production design: Patrice Vermette

Film editing: Joe Walker

Music: Jóhann Jóhannson

Sicario is a suspenseful, well-directed, superbly acted, and finely photographed film whose chief flaw is that it can't decide between what it needs to be, an action thriller, and what it wants to be, a biting commentary on the international social and political consequences of the War on Drugs. As the latter, Sicario could almost be a postscript to Traffic (Steven Soderbergh, 2000), to the point that it casts Benicio Del Toro, who won an Oscar for the earlier film, in the key role of Alejandro, a CIA operative with a personal agenda. Emily Blunt, an actress who seems to be able to do anything (she's been cast as Mary Poppins in a forthcoming sequel), plays Kate, a young FBI agent whom we first see leading a SWAT raid on a house in Chandler, Ariz., that is suspected of being a link to a Mexican drug cartel. Not only is the house full of dozens of corpses, an outlying building explodes when agents try to open a locked trap door, killing two of them. Because of her work on the raid, Kate is offered an assignment on a special team to capture Manuel Diaz, the man responsible for the bombing. The operation is headed by Matt Graver, a jokey, casual, swaggering type whom Kate's partner, Reggie, mistrusts immediately. Kate herself gets stonewalled when she tries to get more details about their mission, and even what part of the government Graver and his mysterious, taciturn partner, Alejandro, work for. It's the CIA, of course, and Kate's presence on the mission is largely to provide an excuse for the presence of the agency on this side of the border, where it's not supposed to operate unless it's working with domestic law enforcement. Their first mission, in fact, is across the border, to Juárez, where they are to pick up an associate of Diaz's who has been captured and is being extradited. Much of this trip is seen from the air: We watch the line of SUV's, looking from above like large black beetles, that carry the members of the task force across the border, smoothly gliding around the traffic backed up at the checkpoint and into the city. It's on the return trip that they encounter a bottleneck: a staged traffic accident strands the convoy in traffic, where they are ambushed by cartel operatives trying to prevent the captured man from testifying. Having survived this encounter, Kate is naturally more determined than ever to get some answers to her questions about the real nature of the mission and the exact roles being played by Graver and Alejandro in it, but she will find that the more she knows, the more danger she is in. Intercut with Kate's story are vignettes of the life of Silvio, a Juárez cop, and his wife and young son. Director Denis Villeneuve and screenwriter Taylor Sheridan keep the significance of these scenes from us until they finally merge with the principal plotline toward the end of the film. It does not end well, of course. Kate has a disillusioning revelation about the purpose of the mission that has put her in harm's way several times, and although the downer ending of the film has an impact of its own when it comes to social and political commentary, it clashes oddly with the generic thriller medium in which it's set. But Villeneuve's direction serves both elements of the film well, Roger Deakins's cinematography received a well-deserved Oscar nomination, and Joe Walker's film editing probably deserved one.

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2014)

I haven't read the Thomas Pynchon novel on which Anderson's film is based, but I've read enough Pynchon to know that his work is founded on a kind of literary playfulness for which there's no cinematic equivalent or even substitute. What Anderson gives us is a kind of loosey-goosey spoof of the private eye genre that works as well as it does because of brilliant casting. Joaquin Phoenix is perfect as Doc Sportello, the perpetually stoned P.I. who is trying to figure out what's going on with his ex-girlfriend Shasta Fay Hepworth (Katherine Waterston) while butting heads with a police detective, "Bigfoot" Bjornsen (Josh Brolin). The time is the 1970s, with Nixon as president and Reagan as California governor, and Anderson milks the period paranoia about drugs and law and order for all it's worth. The plot is as murky as a Raymond Chandler novel, which links the movie with two distinguished predecessors, The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946) and The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973), which really were based on Chandler novels. Inherent Vice isn't as good as either of those films: It's a little too long and a little too caught up in the cleverness of its spoofery. But there's always something or someone -- the cast includes Benicio Del Toro, Owen Wilson, Reese Witherspoon, and Martin Short, among others -- to watch. Brolin is a hoot as Bigfoot: With his crew cut and perpetually clenched jaw he looks for all the world like Dick Tracy -- or maybe Al Capp's parody of Dick Tracy, Fearless Fosdick.

Sunday, September 27, 2015

Traffic (Steven Soderbergh, 2000)

Traffic hasn't held up as well as it might have over the past 15 years, and one reason for that is a bit ironic: The movie was based on a British miniseries, and since the film's debut its central theme, the paralysis of politicians and police in trying to stop the drug trade, and its multiple-track storytelling have been handled more brilliantly by an American miniseries, The Wire (2002-08). It's even possible that the film demonstrates the limits faced by movies as opposed to long-form television in handling stories of complexity and sweep. (Imagine, for example, Game of Thrones or Mad Men or Breaking Bad stuffed into the confines of a two-or-three-hour movie.) Traffic still holds your interest, of course, thanks to some brilliant performances, especially the Oscar-winning one by Benicio Del Toro, as well as the ones by Don Cheadle and Catherine Zeta-Jones. (It's also fun to spot Viola Davis making a solid impression in a tiny part as a social worker.) And Soderbergh's direction deservedly won the Oscar, along with Steven Gaghan's screenplay and Stephen Mirrione's film editing. I would, however, fault Gaghan for the sentimental and melodramatic resolution to the story centering on Michael Douglas as Robert Wakefield, the newly appointed czar of the War on Drugs: It stretches credulity to have Wakefield break down in the middle of his acceptance speech and abandon his post, and the scene in which Wakefield and his wife (Amy Irving) beamingly support their drug-addicted daughter (Erika Christensen) at a twelve-step-program meeting is pure schmaltz. The film also pulls its punches a bit where the wasteful War on Drugs crusade is concerned, even to the point of featuring cameos by real-life politicians William Weld (a Reagan-administration appointee who supervised the Drug Enforcement Administration) and Senators Barbara Boxer, Orrin Hatch, Chuck Grassley, and a surprisingly young-looking Harry Reid as themselves.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)