|

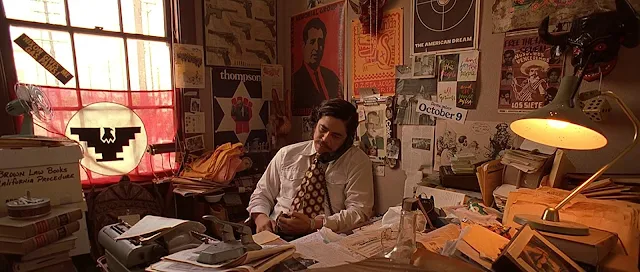

| Jeff Bridges and Gary Busey in The Last American Hero |

Cast: Jeff Bridges, Valerie Perrine, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Gary Busey, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Ned Beatty, Art Lund, Ed Lauter, William Smith, Gregory Walcott, Tom Ligon, Ernie F. Orsatti, Erica Hagen, Jimmy Murphy, Lane Smith. Screenplay: William Roberts, based on articles by Tom Wolfe. Cinematography: George Silano. Art direction: Laurence G. Paull. Film editing: Robbie Roberts, Tom Rolf. Music: Charles Fox.

All good actors act with their eyes, but I don't know anyone who is better at acting with the lower half of their face than Jeff Bridges. Which is to the good in The Last American Hero, because a lot of the film consists of Bridges as Junior Jackson behind the wheel of a race car, his eyes covered with goggles and only the thin slit of his mouth and the determined jut of his jaw visible. But Bridges is also called on to suggest desire (mouth softened, jaw less firmly set), defiance (mouth tense, jaw forward), and defeat (mouth downturned, jaw in retreat). This is not to say that the eyes as well as the voice don't come into play. Bridges has a tour de force scene in the middle of the picture when Junior steps into a record-your-voice booth (a fixture made obsolete by, among other things, the cell phone) to compose an oral letter home to his family, each person -- his disapproving mother (Geraldine Fitzgerald), his supportive brother (Gary Busey), and his incarcerated father (Art Lund) -- receiving an appropriate message as the play of emotions is reflected on his face. There's also a lovely aw-shucks moment when Junior, the hillbilly in the flatlands, deals with the desk clerk in a hotel; Bridges never lapses into caricature in the scene. This also seems to say that Bridges dominates the film, which isn't quite true, since the ensemble consists of not only such skilled character players as Fitzgerald, Busey, and Lund, but also Valerie Perrine as Marge, the racing groupie who adds Junior to her list of racing stars she has bedded, Ned Beatty as Junior's first promoter, and Ed Lauter as the promoter who tries to milk Junior of all the cash he can earn. The film's title comes from the profile of racer Junior Johnson that Tom Wolfe wrote for Esquire in 1965, but it feels a bit misleading. There's nothing particularly heroic about Junior Jackson. (The name and many of the biographical details in Wolfe's article were changed, though Johnson himself served as a consultant and technical advisor on the film.) It's less a biopic than an entertaining dip into an American subculture, somewhat glossy in presentation and memorable mostly for its performances.