|

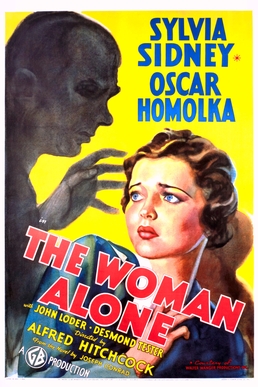

| Diana Wynyard and Anton Walbrook in Gaslight |

Bella Mallen: Diana Wynyard

Rough: Frank Pettingell

Nancy: Cathleen Cordell

Ullswater: Robert Newton

Cobb: Jimmy Hanley

Elizabeth: Minnie Rayner

Director: Thorold Dickinson

Screenplay: A.R. Rawlinson, Bridget Boland

Based on a play by Patrick Hamilton

Cinematography: Bernard Knowles

Music: Richard Addinsell

One of the more famous crimes of MGM was its attempt to destroy the negative and all existing prints of Thorold Dickinson's 1940 version of Gaslight in order to avoid any comparisons between it and the 1944 remake directed by George Cukor. It failed somehow, and the two versions can now be seen back to back. The 1944 film is superb entertainment, winning an Oscar for Ingrid Bergman and showcasing Charles Boyer to very good effect. By its side, Dickinson's version can feel a little undernourished -- or is it just that the later version is overfed, fattened up by Hollywood largesse? I feel very kindly toward the earlier film, which doesn't attempt to disguise the fact that it's sheer melodrama with backstories that try to add psychological realism. All we really need to do is accept the film's Victorian subtext and to know is that Paul Mallen is a foreigner and that his wife, Bella, grew up breathing the pure air of the English countryside to see whose side the film is on. Just the way the Viennese-born Anton Walbrook smooths his mustache is enough to let us know he's a rotter. And was anyone more born to play the gaslighted victim than Diana Wynyard who, with her slight strabismus and her habit of staring into the distance, seems to be seeing things that no one else can? The 84-minute run time sets everything up efficiently and moves steadily through some truly suspenseful moments to its tables-turned conclusion. The 1944 remake runs half an hour longer and while its performances may be more elaborate (and in the case of the teenage Angela Lansbury's conniving maid, superior), Thorold's version keeps us nicely tantalized. The casting of Robert Newton as Bella's cousin is amusing, considering that Newton would go on to make his name as an actor with the terrifying Bill Sikes in David Lean's Oliver Twist (1948). Those of us who saw that film first may suspect that he's up to no good in Gaslight, but we'd be wrong.

Turner Classic Movies