A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Sylvia Sidney. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sylvia Sidney. Show all posts

Thursday, January 9, 2025

Thirty Day Princess (Marion Gering, 1934)

Cast: Sylvia Sidney, Cary Grant, Edward Arnold, Henry Stephenson, Vince Barnett, Edgar Norton, Ray Walker, Lucien Littlefield, Robert McWade, George Baxter, Marguerite Namara. Screenplay: Preston Sturges, Frank Partos, Sam Hellman, Edwin Justus Mayer, based on a story by Clarence Budington Kelland. Cinematography: Leon Shamroy. Art direction: Hans Dreier, Wiard Ihnen. Film editing: Jane Loring. Music: Howard Jackson, John Leipold.

Thursday, October 4, 2018

Street Scene (King Vidor, 1931)

|

| Estelle Taylor, Beulah Bondi, and Eleanor Wesselhoeft in Street Scene |

Sam Kaplan: William Collier Jr.

Anna Maurrant: Estelle Taylor

Emma Jones: Beulah Bondi

Frank Maurrant: David Landau

Vincent Jones: Frank McHugh

Steve Sankey: Russell Hopton

Mae Jones: Greta Granstedt

Greta Fiorentino: Eleanor Wesselhoeft

Bert Easter: Walter Miller

Abe Kaplan: Max Montor

Shirley Kaplan: Ann Kostant

Dick McGann: Allen Fox

Karl Olsen: John Qualen

Willie Maurrant: Lambert Rogers

Filippo Fiorentino: George Humbert

Laura Hildebrand: Helen Lovett

Alice Simpson: Nora Cecil

Director: King Vidor

Screenplay: Elmer Rice

Based on a play by Elmer Rice

Cinematography: George Barnes

Production design: Richard Day

Film editing: Hugh Bennett

Music: Alfred Newman

Eighty-seven years later, King Vidor's Street Scene remains one of the best translations ever made of a stage play into a movie. I think it's largely because Vidor and screenwriter Elmer Rice, adapting his Pulitzer Prize-winning play, avoided the temptation to "open out" the play. The focus of both play and film has to be the façade of the tenement house in which the characters live. Director and writer resist the temptation to go inside, even to show the double murder that forms the climax of the drama. Vidor does give the setting a little more context, with shots of the street and the city rooftops, and there's a scene inside a taxicab arriving at the brownstone, as well as a swish-pan montage of faces popping into windows along the street as people hear the gunshots. But virtually all of the action takes place where it should: on the front steps and in the flanking and upper-story windows of the tenement. What keeps Street Scene from bogging down as one-set films tend to do is the constant mobility of the camera, seeking out a variety of angles on the characters as they come and go. Several of the actors, including Beulah Bondi, John Qualen, Eleanor Wesselhoeft, George Humbert, and Ann Kostant, had performed their roles on Broadway, so they were already keyed into the kind of ensemble playing that Street Scene demands. This was Bondi's film debut, and she's a standout in the key role of the malicious gossip Emma Jones, a hypocrite whose son is a bully and whose daughter behaves like what Emma would call a tramp if she were someone else's daughter. The newcomers to the play also handle themselves admirably, especially Sylvia Sidney and Estelle Taylor as Rose Maurrant and her mother, Anna. The weak link in the cast is William Collier Jr. as Sam Kaplan, who comes across as something of a wuss, unable to defend himself against the bullying Vincent Jones, and a sap in his love scenes with Sidney's Rose, making us wonder what she sees in him. Street Scene also trades a little heavily in stereotypes: the Italians who love music, the Irishman who's a drunk, the Jews who are somewhat isolated from the rest of the tenants, and even the Swede with a comic accent -- one of John Qualen's specialties. Like most of the films produced by Sam Goldwyn, Street Scene has high production values, particularly Richard Day's set, which was modeled on Jo Mielziner's Broadway set; the cinematography by George Barnes with some uncredited assistance from Gregg Toland; and Alfred Newman's score, which features a bluesy Gershwinesque theme that he would re-use in half a dozen other movies even after he left Goldwyn for 20th Century Fox.

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

Fury (Fritz Lang, 1936)

The major Hollywood films about lynching -- this one and The Ox-Bow Incident (William A. Wellman, 1943) -- had white men as the victims, when the unfortunate fact is that black men (and a few women) were statistically by far the more frequent targets of vigilante mobs. Not until Intruder in the Dust (Clarence Brown, 1949), can I think of an American film that confronted the reality of the situation. But I don't think Fritz Lang, making his first American film, was thinking about the United States at all when he made Fury. He had seen rampaging mobs in Germany, which is why he left in 1933. That's why the film reaches its full actuality in its scenes of the mob in full cry. Those scenes alone are almost enough to establish the film as a classic, although much of the rest of Fury feels a bit scattered and aimless. It starts like a conventional romantic drama, with Joe Wilson (Spencer Tracy) and Katherine Grant (Sylvia Sidney) window-shopping for furniture for the home they hope to make when they're married. There's some sidetracking into Joe's relationship with his brothers, Charlie (Frank Albertson) and Tom (George Walcott), which although it seems like it will bear fruit -- Charlie has been associating with some shady characters, to which Tom objects -- is pretty much a narrative dead end. And after Katherine leaves for California, where Joe plans to join her when he makes some money, there's an injection of cuteness when Joe adopts a small dog he names Rainbow.* But when Joe finally gets to California his reunion with Katherine is interrupted by the law, who arrest him on the basis of circumstantial evidence as a suspect in a kidnapping. Gossips immediately take up the story and a mob led by a layabout named Kirby Dawson (Bruce Cabot) storms the jail and burns it down with Joe (and Rainbow) inside. Joe escapes (Rainbow doesn't) and goes into hiding, where he plots revenge. Eventually, when a trial leads to conviction of 22 members of the mob and their sentencing to death, Joe is presented with a moral dilemma: to reveal that he's alive, thereby saving the mob members from hanging, or to stay hidden and get his revenge. This being Hollywood, the decision is pretty much a foregone conclusion. Lang's direction is not so sure-handed as it was in his German films, but it keeps Fury watchable even when you spot the holes and compromises in the screenplay he co-wrote with Bartlett Cormack based on a story by Norman Krasna. Tracy is fine, though the character seems to split into two almost discrete roles: the affable Joe of the first half of the film and the obsessive revenge-seeker of the latter part.

*An oddly prescient name: Rainbow is played by Terry, who also played Toto in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939).

*An oddly prescient name: Rainbow is played by Terry, who also played Toto in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939).

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

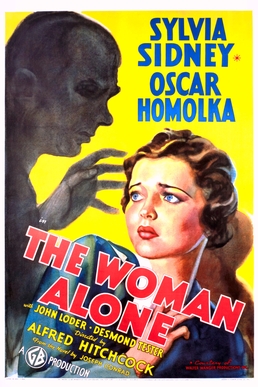

Sabotage (Alfred Hitchcock, 1936)

|

| Sabotage poster with the original title for the U.S. release |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)