A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Edmond Richard. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Edmond Richard. Show all posts

Thursday, July 23, 2020

The Phantom of Liberty (Luis Buñuel, 1974)

Cast: Adriana Asti, Julien Bertheau, Jean-Claude Brialy, Adolfo Celi, Paul Frankeur, Michael Lonsdale, Pierre Maguelon, François Maistre, Hélène Perdrière, Michel Piccoli, Claude Piéplu, Jean Rochefort, Bernard Verley, Monica Vitti, Milena Vukotic. Screenplay: Luis Buñuel, Jean-Claude Carrière. Cinematography: Edmond Richard. Production design: Pierre Guffroy. Film editing: Hélène Plemiannikov.

The most famous, or notorious, scene in The Phantom of Liberty is the one above, in which a group of well-dressed people sit down at a table on flush toilets, and begin to discuss scatological matters. Eventually, one man excuses himself to go to the "dining room," a small private place where he can eat in privacy, an act that evidently would be disgusting if done in public. The film is a kind of tag-team of episodes, in which a secondary character in one scene becomes the central character of the next, all proceeding though dreamlike situations. In movies, dreams are typically not much like our real dreams; they're usually soft-focus and full of portentous events. But Luis Buñuel and his co-scenarist Jean-Claude Carrière know better: Real dreams seem to proceed with the kind of groundedness of daily life, but with logical inconsistencies that we don't question as we're dreaming them. For me, the most dreamlike sequence in The Phantom of Liberty is the one in which the Legendres (Jean Rochefort and Pascale Audret) rush to their daughter's school because she's been reported as having disappeared. When they get there, the little girl is present, but everyone behaves as if she has really disappeared. When they go to the police to report her disappearance, the girl accompanies them and even supplies information about her age, height, and weight to the police, who thank her and the parents and proceed to investigate the case. This is perhaps the most playful of Buñuel's films, though it contains his usual keen satire of bourgeois manners and mannerisms, and is chock-full of ideas about how we conform to conventions and rules that are at base arbitrary and irrational.

Monday, March 23, 2020

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Luis Buñuel, 1972)

|

| Bulle Ogier, Delphine Seyrig, Fernando Rey, Paul Frankeur, Stéphane Audran, and Jean-Pierre Cassel in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie |

The frustration of the bourgeoises in Luis Buñuel's The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie at having their various attempts to sit down at a table and have something like a meal never reaches the furious breaking point that it does for the characters who try to escape from a house party in his The Exterminating Angel (1962), but not because the director had mellowed in the decade between the two films. He had grown more sly and subtle, I think. The world of The Discreet Charm is liminal; the characters are trapped somewhere between dream and reality, between past and future, in a place they're determined to enjoy come what may. In the celebrated dream-within-a-dream, in which one character dreams what another character is dreaming, namely that they're on stage in a play without knowing what their lines are, even then they seem determined to make a go of it, just as the Sénéchals are determined to have sex even though they know their guests have just arrived for luncheon. There's a "keep calm and carry on" quality to these characters that's almost admirable, even when they're faced with the most absurd situations, like a corpse in the next room of the bistro, or a restaurant that has run out of tea and coffee. Not everything in the movie works, I think: The character of the priest/gardener who listens to an old man's confession that he murdered the priest's parents, gives him absolution, then blows him away with a shotgun, seems to me gratuitous -- Buñuel determined to exhibit his contempt for the clergy come what may. But on the other hand, it stayed with me even when I couldn't quite fit it into my overall experience of the film, which is a mad masterpiece.

Wednesday, June 28, 2017

That Obscure Object of Desire (Luis Buñuel, 1977)

|

| Fernando Rey in That Obscure Object of Desire |

Conchita: Carole Bouquet, Ángela Molina

Édouard: Julien Bertheau

Martin: André Weber

Encarnación (Conchita's mother): María Asquerino

The Psychologist: Piéral

Director: Luis Buñuel

Screenplay: Luis Buñuel in collaboration with Jean-Claude Carrière

Based on a novel by Pierre Louÿs

Cinematography: Edmond Richard

Production design: Pierre Guffroy

Fernando Rey's voice dubbed by Michel Piccoli

In my comments on Luis Buñuel's Belle de Jour (1967) I expressed my attitude toward solving what some people think of as that film's riddles as "like concentrating on the threads at the expense of seeing the tapestry." And I'll stick with that. I'm not particularly interested in why Buñuel cast two actresses in the role of Conchita in That Obscure Object of Desire, or why Mathieu occasionally carries around a burlap sack, or even why the central story, of Mathieu's efforts to consummate his desire for Conchita, plays out against a background of terrorist attacks. I know that Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière toyed with the idea of multiple casting even before the film began with a single actress, Maria Schneider, in the role, and that Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina got the part after Buñuel had difficulties working with Schneider. I know, too, that the theory has been advanced that Conchita is a terrorist and that she finally sleeps with Mathieu after he agrees to become one, too -- hence the bomb that explodes at the end of the film. (A theory that reduces a masterwork to the level of hack thriller-filmmaking.) I'm sure that someone has come up with an explanation for the burlap sack, too, along with the fly in Mathieu's drink and the mouse caught in a trap and any other incidental detail that sticks in viewers' minds and can be fitted into an elaborately reductive network of symbolism. But my ultimate response to all of these enigmatic details is delight that they are there, that they popped up in Buñuel's mind as he made the film and that he could and did get away with them. They are what keeps me coming back to Buñuel's films with renewed interest and revived delight, viewing after viewing.

Watched on Filmstruck

Friday, April 22, 2016

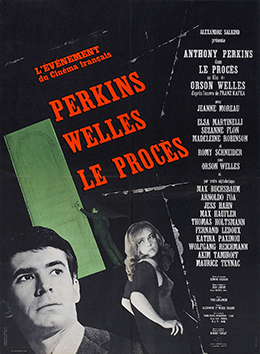

The Trial (Orson Welles, 1962)

There may be sensibilities more different from each other than those of an exiled Midwestern bon vivant and a consumptive Middle European Jew, but they rarely come together in a work of art the way they did in Orson Welles's version of Franz Kafka's The Trial. It was made in that fertile middle period of Welles's career that also saw the creation of Touch of Evil (1958) and Chimes at Midnight (1965), and it holds its own against those two landmarks in the Welles oeuvre. In the end, of course, the Wellesian sensibility dominates, the American tendency to affirmation overcoming (barely) Kafka's pessimism: Welles's Josef K. (Anthony Perkins) is rather more assertive than Kafka's protagonist. He doesn't succumb "Like a dog!" to his assailants but defies them. That said, Perkins, now carrying the indelible stamp of Norman Bates into all his roles, is superlative casting: We can believe that he's guilty -- even if we never find out what his supposed crime is -- while at the same time we sympathize with his plight. The real triumph of the film is in finding the settings in which to stage K.'s ordeal, ranging from K.'s stark, low-ceilinged apartment to bleak modern high-rise apartment and office buildings, to ornate beaux arts exteriors, to the labyrinthine courts of the law. The film was shot in the former Yugoslavia, in Italy, and in the abandoned Gare d'Orsay in Paris. Welles chose a novice, Edmond Richard, who had never shot a feature film, as his cinematographer. Richard went on to shoot Chimes at Midnight, too, as well as some of Luis Buñuel's best films, including The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). The cast includes Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Elsa Martinelli, and Akim Tamiroff, with Welles himself playing the role of Hastler, K.'s attorney, after failing to persuade Jackie Gleason or Charles Laughton to take the part. The Trial is probably longer and slower than it needs to be, and there is some inconsistency of style: The scenes involving Hastler, his mistress (Schneider), and K. are shot with more extreme closeups than the rest of the film, where the sets tend to overwhelm the human figures. And the ending, with its explosion followed by a rather wispy mushroom cloud, is a little too obviously an attempt to bring a story written during World War I into the atomic era. Some think it's a masterpiece, but I would just rank it as essential Welles -- which may or may not be the same thing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)