A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Jean-Claude Brialy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jean-Claude Brialy. Show all posts

Thursday, July 23, 2020

The Phantom of Liberty (Luis Buñuel, 1974)

Cast: Adriana Asti, Julien Bertheau, Jean-Claude Brialy, Adolfo Celi, Paul Frankeur, Michael Lonsdale, Pierre Maguelon, François Maistre, Hélène Perdrière, Michel Piccoli, Claude Piéplu, Jean Rochefort, Bernard Verley, Monica Vitti, Milena Vukotic. Screenplay: Luis Buñuel, Jean-Claude Carrière. Cinematography: Edmond Richard. Production design: Pierre Guffroy. Film editing: Hélène Plemiannikov.

The most famous, or notorious, scene in The Phantom of Liberty is the one above, in which a group of well-dressed people sit down at a table on flush toilets, and begin to discuss scatological matters. Eventually, one man excuses himself to go to the "dining room," a small private place where he can eat in privacy, an act that evidently would be disgusting if done in public. The film is a kind of tag-team of episodes, in which a secondary character in one scene becomes the central character of the next, all proceeding though dreamlike situations. In movies, dreams are typically not much like our real dreams; they're usually soft-focus and full of portentous events. But Luis Buñuel and his co-scenarist Jean-Claude Carrière know better: Real dreams seem to proceed with the kind of groundedness of daily life, but with logical inconsistencies that we don't question as we're dreaming them. For me, the most dreamlike sequence in The Phantom of Liberty is the one in which the Legendres (Jean Rochefort and Pascale Audret) rush to their daughter's school because she's been reported as having disappeared. When they get there, the little girl is present, but everyone behaves as if she has really disappeared. When they go to the police to report her disappearance, the girl accompanies them and even supplies information about her age, height, and weight to the police, who thank her and the parents and proceed to investigate the case. This is perhaps the most playful of Buñuel's films, though it contains his usual keen satire of bourgeois manners and mannerisms, and is chock-full of ideas about how we conform to conventions and rules that are at base arbitrary and irrational.

Saturday, April 20, 2019

I Knew Her Well (Antonio Pietrangeli, 1965)

I Knew Her Well (Antonio Pietrangeli, 1965)

Cast: Stefania Sandrelli, Mario Adorf, Jean-Claude Brialy, Joachim Fuchsberger, Nino Manfredi, Enrico Maria Salerno, Ugo Tognazzi, Karin Dor, Franco Fabrizi, Franco Nero, Robert Hoffmann. Screenplay: Antonio Pietrangeli, Ruggiero Maccari, Ettore Scola. Cinematography: Armando Nannuzzi. Production design: Maurizio Chiari. Film editing: Franco Fraticelli. Music: Piero Piccioni, Benedetto Ghilia.

Tuesday, June 19, 2018

Claire's Knee (Éric Rohmer, 1970)

|

| Aurora Cornu and Jean-Claude Brialy in Claire's Knee |

Aurora: Aurora Cornu

Laura: Béatrice Romand

Claire: Laurence de Monaghan

Mme. Walter: Michèle Montel

Gilles: Gérard Falconetti

Vincent: Fabrice Luchini

Director: Éric Rohmer

Screenplay: Éric Rohmer

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Film editing: Cécile Decugis

Call me naïve, but I never realized before how much Claire's Knee is a kinder, gentler version of Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Éric Rohmer's characters exist to talk, not to act, so that physical seduction recedes in the face of verbal dalliance. The novelist Aurora in Claire's Knee is not, like the Marquise de Merteuil of Pierre Choderlos de Laclos's novel and its many adaptations, out to deflower the innocent, using Jerome, her equivalent of Valmont, as her instrument. For her, the dalliance of older man and teenager is an intellectual exercise, one that might result in a novel for her and only incidentally in pleasure for him. So it's also of importance that of the two jeunes filles en fleurs of the film, it's the more intellectual Laura who truly attracts Jerome, while the strikingly pretty but vapid Claire may be dismissed along with the brief erotic thrill he gets from caressing her titular joint. But has a film ever been sexier without actual nudity and copulation? Add to that the taboos about underage sex, and we get a film taut with suspense yet essentially light-hearted and full of wisdom about the complexities of love.

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Le Beau Serge (Claude Chabrol, 1958)

Le Beau Serge has been called the first film of the French New Wave because it was made before the first features by Claude Chabrol's fellow Cahiers du Cinéma critics, François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960). The two later films were bigger successes internationally, but the influence of Chabrol's debut on the look, the narrative, and the technique of film continued to be felt, and his next movie, Les Cousins (1959), established Chabrol's reputation. Like Truffaut and Godard, who made international stars of Jean-Pierre Léaud and Jean-Paul Belmondo with their features, Chabrol launched the careers of Gérard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy, who appeared in his first two films. In Le Beau Serge, Blain plays the title role, a young man who, by staying in his provincial village (Chabrol's own home town of Sardent), becomes an alcoholic layabout, trapped in an unhappy marriage. Brialy plays François, an old friend of Serge's, who left Sardent and became a success, but now returns home after a long absence to recuperate from a lung ailment. The roles are striking in both the similarity to and the differences from the ones Blain and Brialy play in Les Cousins, which takes place in Paris, where Blain is the strait-laced provincial and Brialy is his dissipated cousin. Le Beau Serge follows François's somewhat misguided attempt to help Serge clean up his life, which is complicated when François begins an affair with Serge's sister-in-law, Marie (Bernadette Lafont). In the climax of the film, Serge's wife, Yvonne (Michèle Méritz), goes into labor with the child everyone in the village expects to be deformed or stillborn, as their first child was. In a howling snowstorm, François takes it on himself to go in search of the village's doctor, and then looks for Serge, who is sleeping off a drunk in a chicken coop. The concluding scene, of Serge convulsed in hysterical laughter, is profoundly ambiguous. Chabrol's use of the actual village of Sardent, including many of its townspeople as actors, is brilliantly done, greatly aided by Henri Decaë's cinematography. Les Cousins is a more sophisticated and satisfying film, but it really has to be seen in tandem with Le Beau Serge. Both actors are terrific, but Blain attracted more attention because of his supposed resemblance in both looks and style to James Dean, though to my mind he recalls Montgomery Clift more than Dean.

Saturday, December 26, 2015

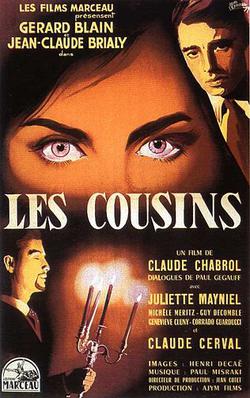

Les Cousins (Claude Chabrol, 1959)

Chekhov's gun plays a major role in Les Cousins, heightening the suspense about who will use it on whom. But the film isn't a suspense thriller, despite Chabrol's admiration for Hitchcock, so much as it is a deliciously perverse adaption of some classic fables: the country mouse and the city mouse, and the ant and the grasshopper. It also resonates ironically with Balzac's Lost Illusions, the novel that a bookseller (Guy Decomble) allows Charles (Gérard Blain) to "steal" from his shop. In the Balzac novel, a young man from the provinces goes to Paris to seek fame, fortune, and love, and his misadventures wreak havoc on himself and the people he loves. In Les Cousins, country mouse/ant Charles goes to Paris to share an apartment with his cousin, Paul (Jean-Claude Brialy), the city mouse/grasshopper, while both study law. Paul is a somewhat decadent hedonist, who tries to introduce the straiter-laced Charles, who is very much dedicated to his mother back home, to the delights of the city. One of these delights is the promiscuous Florence (Juliette Mayniel), with whom Charles falls in love, only to have things end badly when she chooses to live with Paul instead. Chabrol fills the movie with quirky, somewhat sinister characters, though never turns the film into a clear-cut tale of good vs. evil. Innocence doesn't triumph over cynicism here, though cynicism pays a price, which is what makes Chabrol's film such a grandly satisfying one to watch and to think about afterward. Blain and Brialy (in a suitably Mephistophelean mustache and beard) are brilliant, and the cinematographer, Henri Decaë, gives us a grand evocation of Paris in the 1950s.

Sunday, October 4, 2015

A Woman Is a Woman (Jean-Luc Godard, 1961)

|

| Jean-Claude Brialy and Anna Karina in A Woman Is a Woman |

Angela: Anna Karina

Alfred Lubitsch: Jean-Paul Belmondo

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard

Cinematography: Raoul Coutard

Production design: Bernard Evein

Music: Michel Legrand

Orson Welles is often quoted as having said, when he saw the production facilities available to him at RKO, "This is the biggest electric train set any boy ever had!" I imagine Jean-Luc Godard saying something like that when he was told that he could make his second feature film, after the success of Breathless (1960), in color and Franscope (an anamorphic wide-screen process like Cinemascope). But of course Godard and his cinematographer, Raoul Coutard, had no intention of using the wide screen for its conventional purpose, the epic and spectacular. Instead, many of the tricks the director and the cinematographer pulled off in A Woman Is a Woman were playful ones, like filming the tiny, cramped apartment of Angela and Émile in a medium more suited to Versailles. The effect is not only slightly giddy, but it also serves to emphasize the difficulties the couple are having in their relationship. The movie is brightly inconsequential, the kind of colorful musicalized nonsense that Jacques Demy would master a few years later with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), using the same composer Godard does, Michel Legrand. The success of Breathless seems to have gone to Godard's head a bit: He enlists its star, Jean-Paul Belmondo, as the third leg of the movie's romantic triangle, and has him speak a line about not wanting to miss Breathless on TV. Belmondo also encounters Jeanne Moreau in a cameo bit, asking her how Jules and Jim is going -- Godard's fellow New Wave sensation, François Truffaut, was in the midst of filming it with Moreau. The best thing A Woman Is a Woman has going for it is Karina, who was about to become Godard's muse and for a while his wife.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)