|

| Bruno Ganz and Dennis Hopper in The American Friend |

Jonathan Zimmermann: Bruno Ganz

Marianne Zimmermann: Lisa Kreuzer

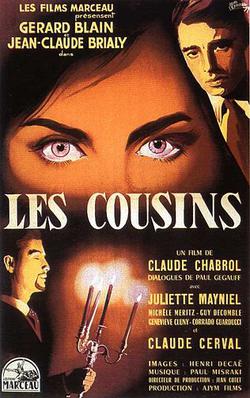

Raoul Minot: Gérard Blain

Derwatt: Nicholas Ray

The American: Samuel Fuller

Marcangelo: Peter Lilienthal

Ingraham: Daniel Schmidt

Rodolphe: Lou Castel

Director: Wim Wenders

Screenplay: Wim Wenders

Based on a novel by Patricia Highsmith

Cinematography: Robby Müller

Music: Jürgen Knieper

Film editing: Peter Przygodda

When I called Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) "stoner noir" yesterday, I thought I had pretty much exhausted the genre with the exception of Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye (1973). But then I watched The American Friend and realized my error. Actually, the plot and milieu of The American Friend, loosely adapted from Patricia Highsmith's Ripley's Game, is material more for a thriller than for film noir's brooding exploration of the lower depths of criminality. Here we are in what might be called the upper depths: art fraud and murder for hire. But mostly The American Friend is an exercise in watching the phenomenon that was Dennis Hopper, who came to the set fresh from the horrors, the horrors of working on Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979). It is, as most of Hopper's performances were, an exercise in self-destruction. And perfectly cast against him, in what was his first important film, is Bruno Ganz, struggling to keep his head. Ganz and Hopper eventually came to blows off-set, and then spent a night drinking their way into a fast friendship and an entertaining tandem performance. There is a blink-and-you'll-miss-it character to the film's set-up exposition about why mild-mannered picture framer Jonathan Zimmermann gets caught up in the manipulations of Tom Ripley and Raul Minot, but it doesn't matter much. Zimmermann's first job for Minot is beautifully staged, with just enough eccentric touches -- Zimmermann colliding with a dumpster and a stranger (Jean Eustache, one of the director cronies Wenders cast in his film) offering him a Band-Aid -- to make it more than routine thriller stalking. And the sequence on the train is a classic of cutting between on-location and studio set filming, culminating in Zimmerman's exhilarated scream from the view port on the engine. To my taste, The American Friend is a little too loosey-goosey in exposition and a little too self-indulgent in its director cameos, making it catnip for cinéastes but maybe not solid enough for mainstream viewers. The thriller bones show through, making me want to see the material done a little more slickly and conventionally. But as personal filmmaking goes, it's fascinating.

Watched on Filmstruck Criterion Channel