|

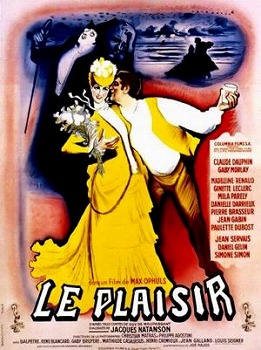

| Georges Grey and Gaby Morlay in Quadrille |

One of Sacha Guitry's strengths as a filmmaker was that he was a prolific playwright who knew how to craft dialogue and plot. One of Sacha Guitry's weaknesses is that he was a prolific playwright who never quite mastered the difference between a play and a film -- namely, that the actors in a film have to perform without benefit of an audience, and the dialogue they're speaking shouldn't ramble on, as it tends to do without the interruptions of laughter or other unscripted responses of a live audience. The masters of film comedy -- I'm thinking here of directors like Howard Hawks and George Cukor -- knew that a continued stream of bons mots or wisecracks needed the right pacing to keep a movie theater audience from covering up the best moments. But Guitry's characters in Quadrille talk non-stop, none more so than the director-writer-star himself, never giving us a break to savor what has been so wittily said or so poignantly evoked. Quadrille is a pleasant French romantic comedy about a publisher with a mistress who's a star on the stage. She cuckolds him with a handsome American movie star, just as the publisher is about to propose marriage to her. When she learns that she has just blown the possibility of marrying him, and it looks like the movie star has decamped, she attempts suicide. But things are set right by the fourth player in this quadrille, a pretty reporter who manages to sort things out, rescuing the actress in the nick of time, sending her off with the movie star, and taking the publisher for herself. Guitry plays the publisher, with Gaby Morlay as the actress, Jacqueline Delubard as the reporter, and Georges Grey -- who had made his film debut in a small role in Guitry's The Pearls of the Crown (1937) -- as the movie star. There's a certain French insouciance about playing the actress's suicide attempt for comedy -- it doesn't work in the more American context of Billy Wilder's Sabrina (1954), for example.