|

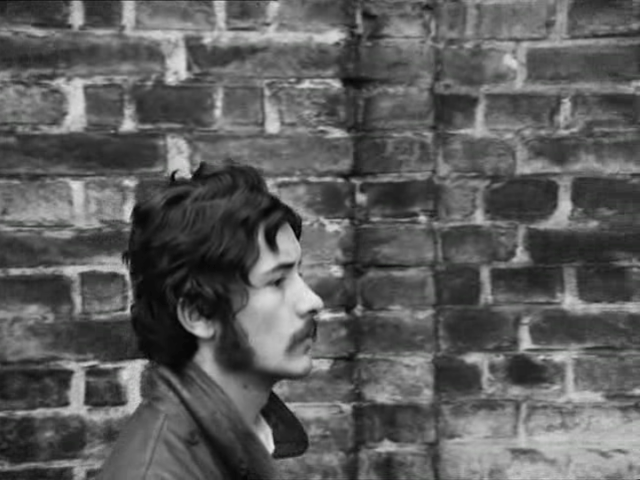

| Harry Baer in Gods of the Plague |

Joanna Reiher: Hanna Schygulla

Margarethe: Margarethe von Trotta

Günther: Günther Kaufmann

Carla Aulaulu: Carla Egerer

Magdalena Fuller: Ingrid Caven

Policeman: Jan George

Mother: Lilo Pempeit

Marian Walsch: Marian Seidowsky

Joe: Micha Cochina

Inspector: Yaak Karsunke

Supermarket Manager: Hannes Gromball

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Screenplay: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Cinematography: Dietrich Lohmann

Production designer: Kurt Raab

Film editor: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Music: Peer Raben

The Rainer Werner Fassbinder stock company is one of the wonders of film, mixing up their roles throughout his movies in often amusing ways. This is the second film to feature Franz Walsch, a name Fassbinder took as his own sometimes -- including in the credits for Gods of the Plague, which list "Franz Walsch" as the film editor. In the first Franz Walsch feature, Love Is Colder Than Death (1969), the character, a young hood, was played by the decidedly homely Fassbinder, but in this one he becomes the considerably more handsome Harry Baer, preening his luxuriant mustache. Franz is released from prison at the film's start, and he soon becomes involved with two women, Joanna (played once again by Hanna Schygulla) and Margarethe (Margarethe von Trotta, who would soon come into her own right as a director as well as actress). Like the earlier film, Gods of the Plague takes place in the rather inept underworld of Munich, in which Franz teams up with Günther, aka Gorilla, to pull off a supermarket robbery that's doomed to deadly failure. Also like Fassbinder's other early films, it's played with a deadpan, emotionless affect by all concerned, so that you sometimes have to laugh at the disconnect of situations, events, and relationships that would be shocking or horrifying in the real world but are treated as no big deal by the characters in the film. It was obviously inspired by the attempts at coolness essayed by the characters in the French New Wave, but even Godard's delinquents seemed to be having more fun than Fassbinder's do. A difference between being French and being German perhaps? The cast also features other members of the stock company such as Irm Hermann and Kurt Raab (who doubles as production designer) as well as Fassbinder in very small roles.