It takes great acting to steal a movie from Jack Nicholson. In short, it takes Michael Caine. In Blood and Wine, Caine plays Victor, a sleazy ex-con with a hair trigger and a death-bed cough. It's a more physically violent role than we usually see Caine in, and it's startling to see him erupt, slamming into a hapless victim like Henry (Harold Perrineau), who just happens to get caught up in the movie's plot mechanism. Otherwise, Blood and Wine is mostly a forgettable throwback, informed by movies of the 1940s and 1970s, a neo-noir directed by Bob Rafelson, whose directing career was launched with movies starring Nicholson, like Five Easy Pieces (1970) and The King of Marvin Gardens (1972). It's a bleakly cynical movie with no good guys, except that everyone in it looks a little better in comparison with Caine's Victor.

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Jack Nicholson. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jack Nicholson. Show all posts

Monday, July 22, 2024

Blood and Wine (Bob Rafelson, 1996)

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Michael Caine, Stephen Dorff, Judy Davis, Jennifer Lopez, Harold Perrineau, Robyn Peterson, Mike Starr. Screenplay: Nick Villiers, Bob Rafelson, Alison Cross. Cinematography: Newton Thomas Sigel. Production design: Richard Sylbert. Film editing: Steven Cohen. Music: Michal Lorenc.

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Shelley Duvall, Danny Lloyd, Scatman Crothers, Barry Nelson, Philip Stone, Joe Turkel, Anne Jackson. Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Diane Johnson. Cinematography: John Alcott. Production design: Roy Walker. Film editing: Ray Lovejoy. Music: Wendy Carlos, Rachel Elkind.

There are those of us who don't love The Shining. There used to be a lot more of us: When it first opened, Stanley Kubrick's movie met with lukewarm reviews and a general feeling that it was a well-made but not particularly interesting horror movie. Today, the word tossed about often is "masterpiece," and the ranking on IMDb is a whopping 8.4 out of a possible 10. But for me the film is all tricks and no payoff, and the central problem is Jack Nicholson. I know, it's an intensely committed performance, like all of his. But it's one-note crazy almost from the start, partly because the demonic eyebrows and sharklike grin are in full play. Jack Torrance should go mad, nut just be mad, and Kubrick hasn't allowed Nicholson to make the transition of which the actor is fully capable. But Kubrick is less interested in creating characters than in playing with shock effects. Shelley Duvall is forced to turn from a loving and resourceful mother to a blithering nutcase before reverting to the former by the end of the film. Then, too, there are the clichés on which the story is based: the isolated hotel built on the old Indian burying ground, the hedge maze, the kindly but obviously doomed Black man, and so on. Even the supernatural elements are muddled: What does the extrasensory communication, the "shining" of Danny (Danny Lloyd) and Halloran (Scatman Crothers), have to do with the presence of ghosts in the hotel beyond being a way to provide a rescue at the end? The film works for me only if I let myself take on some of its director's notorious cold detachment, and I want movies to let me do more than just admire technique.

Tuesday, October 1, 2019

Carnal Knowledge (Mike Nichols, 1971)

Carnal Knowledge (Mike Nichols, 1971)

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Ann-Margret, Art Garfunkel, Candice Bergen, Rita Moreno, Cynthia O'Neal, Carol Kane. Screenplay: Jules Feiffer. Cinematography: Giuseppe Rotunno. Production design: Richard Sylbert. Film editing: Sam O'Steen.

Carnal Knowledge begins as a light comedy of manners set in the late 1940s, when college students were supposedly less casual and more poorly informed about sex. Jonathan (Jack Nicholson), who claims to be more sexually experienced than his Amherst roommate, Sandy (Art Garfunkel), gives Sandy some advice on how to approach Smith College student Susan (Candice Bergen) at a mixer. The scene has some of the keen ear for awkward attempts at communication found in screenwriter Jules Feiffer's cartoons and in director Mike Nichols's comedy routines with Elaine May. Eventually, Sandy and Susan get together, with Jonathan still coaching Sandy on sex, until Jonathan himself makes his own moves -- unknown to Sandy -- on Susan. He succeeds, in an excruciating scene in which Susan's confusion about the loss of her virginity plays across her face, partly obscured by the grunting Jonathan on top of her. And from then the film becomes increasingly sour, as the years pass and the misogynistic Jonathan continues to meddle in Sandy's life but also makes a mess of his own relationships with women. He takes up with Bobbie, a model played by Ann-Margret, for what begins as a passionate fling and ends in misery. By the end of the film he is being serviced by Louise (Rita Moreno), a prostitute whom he hires to perform a routine -- and abuses when she deviates from it -- designed to give him an erection. It's a sad, rather hopeless film that despite fine performances from all the actors never quite convinces us that its characters are anything but puppets of the writer and director. Jonathan and Sandy seem incapable of change and growth. Something makes me think that Carnal Knowledge would have been a better film if it had been told from the women's point of view, that it would have made a more telling point about the male ego and about the great gulf between the sexes if we had seen Jonathan and Sandy through Susan and Bobbie's eyes. We get glimpses of that, but Susan disappears from the film after she marries Sandy and he, egged on by Jonathan, drifts into mid-life affairs. Bobbie's entrapment into Jonathan's world leads to a failed suicide attempt, after which she, too, vanishes from the story. Feiffer and Nichols never make it clear whether their film is a satire on sex in modern society or just a particularly bleak story about unhappy people.

Sunday, June 24, 2018

Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969)

|

| Peter Fonda and Jack Nicholson in Easy Rider |

Billy: Dennis Hopper

George Hanson: Jack Nicholson

Connection: Phil Spector

Stranger on Highway: Luke Askew

Lisa: Luana Anders

Sarah: Sabrina Scharf

Jack: Robert Walker Jr.

Mary: Toni Basil

Karen: Karen Black

Director: Dennis Hopper

Screenplay: Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, Terry Southern

Cinematography: László Kovács

Art direction: Jeremy Kay

Film editing: Donn Cambern

In his book Have You Seen... David Thomson discusses all the ways in which Easy Rider became a landmark film, usually cited along with 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967), and The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967) as one of the harbingers of the revolution in American filmmaking at the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s, movies that signaled the emergence of a new, younger film audience. And then Thomson calls Easy Rider "unwatchable." As one who was part of that new, younger film audience, I tend to agree. Except for every moment when Jack Nicholson is onscreen, launching one of the great film careers, Easy Rider really is unwatchable. The drug buy and sale that sets up the odyssey of Wyatt and Billy across America is clumsily scripted and filmed. The beginnings of their motorcycle tour is remarkable only for the nod to John Ford in the glimpses of Monument Valley, and the stay in the hippie commune is tedious. The one interesting moment comes when László Kovács's camera does a 360 degree pan across the faces of the communards, an echo of the similar pan of the faces sheltering in the barn in Andrei Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev (1966) and maybe of Raoul Coutard's pan around the farmyard in Jean-Luc Godard's Weekend (1967), except that there's little of interest in the faces assembled in the commune. (The sequence only made me realize that the people gathered there are now, if still alive, collecting Social Security.) But when Nicholson appears, the film snaps sharply into focus, only to sag back into its old tired ways. The scene in which George Hanson is murdered is awkwardly staged, so that we don't really know what's going on until it's over, and the rest of the film is just waiting for the inevitable demise of Wyatt and Billy. The acid trip in the New Orleans cemetery is little more than a collection of avant garde clichés. There are a few compensations, like the music on the soundtrack, and Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper do a good job of delineating Wyatt and Billy, the latter dangerously volatile, the former more cautious and laid back. But Easy Rider is showing its age, looking more and more like a 50-year-old movie, while some of its other celebrated contemporaries wear their age with grace.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

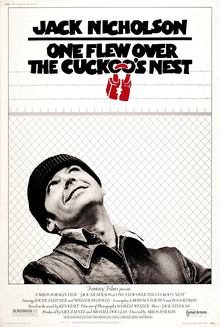

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (Milos Forman, 1975)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest is beginning to show its age, as any 41-year-old movie must. It no longer exhibits the freshness that won it acclaim as a masterpiece and raked in the five "major" Academy Awards: picture, director, actor, actress, and screenplay -- only the second picture in history to do that: The first was It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934), and only one other picture, The Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991), has subsequently accomplished that feat. Today, however, One Flew has the look of a skillfully directed but somewhat predictable melodrama; its tragic edge has been blunted by familiarity. In treating the material, director Forman goes for straightforward storytelling, without showing us something new or personal as an auteur. And as time has passed, some of the elements of the source, Ken Kesey's novel, that screenwriters Laurence Hauben and Bo Goldman took pains to mitigate -- namely the countercultural glibness and antifeminism -- have begun to show through. It's harder today to wholeheartedly cheer on the raw, anarchic antiauthoritarianism of McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) or to accept as a given the unmitigated villainy of Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher). We want our protagonists and antagonists to be a little more complicated than the film allows them to be. There are still many who think it a great film, but if it is, I think it's largely because it's the perfect showcase for a great talent -- Nicholson's -- supported by an extraordinary ensemble that includes a shockingly young-looking Danny DeVito, Scatman Crothers, Sidney Lassick, Christopher Lloyd, Will Sampson, and a touchingly vulnerable Brad Dourif.

Thursday, February 4, 2016

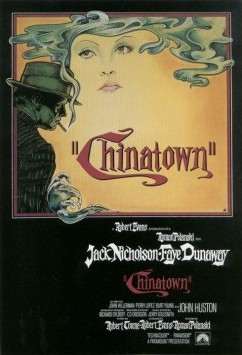

Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974)

Where there's money, there's murder, and where the sun shines brightest, the shadows are darkest. That's why film noir was invented in Hollywood, and why California's greatest contribution to American literature may have been the pulp fiction of James M. Cain and the detective novels of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross Macdonald. Chinatown, which draws on that tradition, has a kind of valedictory quality about it, harking back to the 1930s roots of noir, although the genre's heyday was the postwar 1940s and paranoia-filled early 1950s. (Curtis Hanson would exploit that latter era in his 1997 film L.A. Confidential.) But it's also very much a film of the 1970s, which is to say that 42 years have passed and Chinatown is showing its age. The revelation that Katherine (Belinda Palmer) is both the daughter and the sister to Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) no longer has the power to shock that it once did, incestuous rape having become a standard trope of even TV drama. Nor does the "dark" ending, which director Roman Polanski insisted on, despite screenwriter Robert Towne's preference for a more conventionally hopeful resolution, seem so revolutionary anymore. It remains a great film, however, thanks to those quintessential '70s stars, Dunaway and Jack Nicholson, in career-defining performances, the superb villainy of John Huston's Noah Cross, and Roman Polanski's deft handling of Towne's intricate screenplay, carefully keeping the film limited to the point of view of Nicholson's Jake Gittes. Production designer Richard Sylbert and costume designer Anthea Sylbert (Richard's sister-in-law), aided by cinematographer John A. Alonzo, are responsible for the stylish evocation of 1930s Los Angeles. The atmospheric score is by Jerry Goldsmith.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)