A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Jerry Goldsmith. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jerry Goldsmith. Show all posts

Sunday, December 8, 2019

Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982)

Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982)

Cast: Craig T. Nelson, JoBeth Williams, Beatrice Straight, Dominique Dunne, Oliver Robins, Heather O'Rourke, Michael McManus, Virginia Kiser, Martin Casella, Richard Lawson, Zelda Rubinstein, James Karen. Screenplay: Steven Spielberg, Michael Grais, Mark Victor. Cinematography: Matthew F. Leonetti. Production design: James H. Spencer. Film editing: Michael Kahn. Music: Jerry Goldsmith.

Poltergeist has Steven Spielberg written all over it -- literally, since he wrote the story and collaborated on the screenplay, but also thematically, since its setting is the suburbia in which he grew up and which he portrayed in so many of his films. So it's no surprise that the controversy over how much of the film is really Tobe Hooper's continues to this day. It's clear that Poltergeist is a lot closer in tone and technique to Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) than it is to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1972). That in itself should put an end to any arguments over authorship. I am not a fan of horror movies, and I found Hooper's earlier film simply unpleasant -- shocks without substance. Not that there's much substance in Poltergeist, either. It's full of hokum about the afterlife and exploitation of some elementary terrors, but not much else that would ever make me want to think about it, let alone watch it again.

Friday, October 27, 2017

Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979)

|

| Sigourney Weaver, Harry Dean Stanton, Yaphet Kotto, John Hurt, Tom Skerritt, Veronica Cartwright, and Ian Holm in Alien |

Dallas: Tom Skerritt

Lambert: Veronica Cartwright

Brett: Harry Dean Stanton

Kane: John Hurt

Ash: Ian Holm

Parker: Yaphet Kotto

Director: Ridley Scott

Screenplay: Dan O'Bannon, Ronald Shusett

Cinematography: Derek Van Lint

Production design: Michael Seymour

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) posited that extraterrestrial beings might not be bent on world domination or worse, but instead were just looking to be friendly neighbors. Spielberg went on to reinforce that idea in 1982 with E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. It was a kind of reversal of the treatment of space creatures in 1950s sci-fi films, born of Cold War paranoia. But although the Spielbergian vision informed several other successful films, including John Carpenter's Starman (1984), the truth is that when it comes to movies, paranoia is fun. No movie established that more clearly than Alien, whose huge success launched a whole new era of shockers from outer space, including Carpenter's The Thing (1982). Almost 40 years later, Alien still holds up, while the Spielberg films are looking a bit sappy. Is that a commentary on the movies themselves, or on us? Alien benefits from near-perfect casting and from outstandingly creepy design, making the most of the work of H.R. Giger on the alien and its environment and of Carlo Rambaldi (who had also created the benign aliens of Close Encounters and E.T.) on animating the creature. While it's true that time has not been entirely kind to some parts of the design -- such as the cathode ray tube monitors for the ship's computers, which would definitely be outmoded in 2037 when the film is set -- everything else has become sci-fi standard, including the depiction of the Nostromo as an aging tub of a ship whose maintenance crew, Brett and Parker, gripe about being paid less than the management staff. Scott doesn't labor over the implicit critique of corporate capitalism that will become more prominent in the sequels, but it's nice to see it there.

Thursday, September 15, 2016

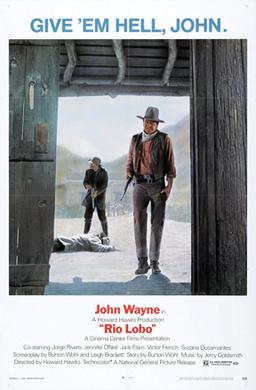

Rio Lobo (Howard Hawks, 1970)

Not much of the opening sequence of Rio Lobo, an exciting and ingenious train robbery, was probably directed by Howard Hawks. He was injured during the filming, and much of it was accomplished by his second-unit directors, Yakima Canutt and Mike Moder, who are generously given screen credits -- just as Hawks gave a co-director credit to Arthur Rosson for the cattle drive scenes in Red River (1948). The sequence is also the best thing in the film. What follows feels for the most part tired, derivative, and poorly cast, which is a shame, since it was Hawks's last film. We'd all like our favorite directors to go out on a high note, but it seldom happens: There aren't many who regard Alfred Hitchcock's Family Plot (1976), Billy Wilder's Buddy Buddy (1981), or John Ford's 7 Women (1966) as sufficiently valedictory achievements, either. Still, Rio Lobo has its moments, most of them supplied by old pros like John Wayne and Jack Elam. It has cinematography by the masterly William H. Clothier and a score by Jerry Goldsmith. What it doesn't have is a competent supporting cast, particularly in the key roles played by Jorge Ribero and Jennifer O'Neill. Ribero's success in Mexican films, combined with his good looks, led Hollywood to give him a try, but he's out of his depth as a foil for Wayne and is obviously uncomfortable in his second language. O'Neill, a former model, is the last in the line of "Hawksian women" whose ability to stand up to men gave a certain bright tension to his films, and who were previously embodied by the likes of Katharine Hepburn, Jean Arthur, Rosalind Russell, and Lauren Bacall. But when O'Neill flubs an attempt to match Wayne at Hawks's characteristic overlapping repartee, it's clear that the game is over. O'Neill's character virtually disappears from the later part of the film, and the climactic scene is given to another character played by Sherry Lansing, who at least recognized her limitations as an actress and gave it up to become a film studio executive. Rio Lobo, a more or less acknowledged semi-remake of Rio Bravo (1959) and its remake, El Dorado (1966), is not without its rewards for those who relish old-style Westerns, but coming from an era when Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah were reinventing the genre it feels like a sad anachronism.

Thursday, February 4, 2016

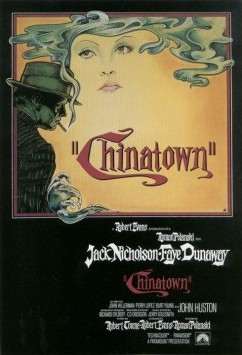

Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974)

Where there's money, there's murder, and where the sun shines brightest, the shadows are darkest. That's why film noir was invented in Hollywood, and why California's greatest contribution to American literature may have been the pulp fiction of James M. Cain and the detective novels of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross Macdonald. Chinatown, which draws on that tradition, has a kind of valedictory quality about it, harking back to the 1930s roots of noir, although the genre's heyday was the postwar 1940s and paranoia-filled early 1950s. (Curtis Hanson would exploit that latter era in his 1997 film L.A. Confidential.) But it's also very much a film of the 1970s, which is to say that 42 years have passed and Chinatown is showing its age. The revelation that Katherine (Belinda Palmer) is both the daughter and the sister to Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) no longer has the power to shock that it once did, incestuous rape having become a standard trope of even TV drama. Nor does the "dark" ending, which director Roman Polanski insisted on, despite screenwriter Robert Towne's preference for a more conventionally hopeful resolution, seem so revolutionary anymore. It remains a great film, however, thanks to those quintessential '70s stars, Dunaway and Jack Nicholson, in career-defining performances, the superb villainy of John Huston's Noah Cross, and Roman Polanski's deft handling of Towne's intricate screenplay, carefully keeping the film limited to the point of view of Nicholson's Jake Gittes. Production designer Richard Sylbert and costume designer Anthea Sylbert (Richard's sister-in-law), aided by cinematographer John A. Alonzo, are responsible for the stylish evocation of 1930s Los Angeles. The atmospheric score is by Jerry Goldsmith.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)