Between Two Worlds (Edward A. Blatt, 1944)

Cast: John Garfield, Paul Henreid, Sydney Greenstreet, Eleanor Parker, Edmund Gwenn, George Tobias, George Coulouris, Faye Emerson, Sara Allgood, Dennis King, Isobel Elsom, Gilbert Emery. Screenplay: Daniel Fuchs, based on a play by Sutton Vane. Cinematography: Carl E. Guthrie. Art direction: Hugh Reticker. Film editing: Rudi Fehr. Music: Erich Wolfgang Korngold.

Sutton Vane's old warhorse of a play Outward Bound made its debut on Broadway in 1924 and became a community theater staple for many years after. It's a fantasy about the afterlife, in which passengers on a ship gradually come to realize that they're dead and will be judged by a man known as the Examiner, who will send them to their just deserts. Warner Bros. filmed it in 1930 with Leslie Howard as the cynical newspaperman Tom Prior and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. as the suicidal Henry, a role Howard had played on stage. In 1944 the studio decided it was time for a remake that would update the story to the war years: A group of people are desperate to get out of England during the bombing and decide to risk sailing to America. Among them is Henry Bergner, a concert pianist who has been part of the Resistance in France but whose nerves have been shattered so that he can't take it anymore. When he's turned down because he doesn't have an exit permit, he decides to kill himself, so he returns to the flat he shares with his wife, Ann (Eleanor Parker), seals the windows shut, and turns on the gas. But Ann has pursued him to the steamship office, and when she finds out he has just left, she rushes into the street just in time to see a car carrying people who have successfully booked passage -- we have been introduced to them earlier -- blown to bits. She hurries on to the flat and discovers what Henry has done, so she decides to join him in death. Cut to the ship, where she and Henry join the people who have just been blown up. Henry and Ann realize that they're dead, but they're advised by the ship's steward, Scrubby (Edmund Gwenn), not to let the others know just yet. And so it goes, as the passengers gradually awake to the truth of their condition and undergo judgment by the Examiner, who was once an Anglican clergyman. Sydney Greenstreet plays him with his usual affably sinister manner -- in his scenes with Henreid it's a bit like watching Victor Laszlo being judged by Kasper Gutman. The bad people -- an arrogant capitalist played by George Coulouris and a snobbish society dame played by Isobel Elsom -- get dispatched to punishment; the sinful but worthy -- Garfield's raffish journalist and Faye Emerson's conscience-stricken playgirl/actress -- are provided with a measure of redemption. And then there are the suicides, Henry and Ann. It's revealed that their lot is to serve aboard these postmortem ships for eternity, like the steward Scrubby, who had killed himself. Since condoning suicide was taboo, especially under the Catholic-administered Production Code, the script has to provide an out for the attractive, repentant couple, and it does. There's a lot of stiff acting in the movie -- Garfield's is the only really naturalistic performance -- and the dialogue is full of heavy-handed exposition speeches. The capitalist and the socialite never rise above caricature, and there's a sentimental tribute to mother love. This is the first of only three films directed by Edward A. Blatt, and it's easy to see why there weren't more.

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label John Garfield. Show all posts

Showing posts with label John Garfield. Show all posts

Sunday, December 22, 2019

Sunday, August 11, 2019

The Breaking Point (Michael Curtiz, 1950)

|

| John Garfield and Patricia Neal in The Breaking Point |

If the setup, an honest fishing-boat captain forced into some intrigue he really doesn't want to get mixed up in, sounds familiar, that's because The Breaking Point was based on Ernest Hemingway's To Have and Have Not. And that had been the basis for a much looser adaptation (it mostly just kept the title) by Howard Hawks, with the aid of screenwriters Jules Furthman and William Faulkner, in 1944. But here, instead of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, we get John Garfield and Patricia Neal -- considerable actors both, but striking no sparks and teaching no one how to whistle. The New York Times's ineffable film critic Bosley Crowther much preferred The Breaking Point, calling the Hawks version a "feeble swing and a cut at Ernest Hemingway's memorable story of a tough guy" whereas director Michael Curtiz and screenwriter Ranald MacDougall "got hold of that fable and socked it into a four-base hit." Crowther's baseball metaphors aside, it's possible to admire the professionalism of Curtiz's direction and the adherence to a downer ending for Garfield's Harry Morgan, while still feeling that in their film Hawks, Furthman, Faulkner, Bogart, Bacall, et al. knew and displayed a lot more about the Hemingway virtue of grace under pressure.

Tuesday, July 2, 2019

Nobody Lives Forever (Jean Negulesco, 1946)

Cast: John Garfield, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Walter Brennan, Faye Emerson, George Coulouris, George Tobias, Robert Shayne, Richard Gaines, Richard Erdman. Screenplay: W.R. Burnett, based on his novel. Cinematography: Arthur Edeson. Art direction: Hugh Reticker, Max Parker. Film editing: Rudi Fehr. Music: Adolph Deutsch.

Changes of heart are always risky, especially in film noir, so when Nick Blake (John Garfield) falls in love with the rich widow Gladys Halvorsen (Geraldine Fitzgerald), who has been chosen as the mark in a con game, things get a little screwed up. Originally planned as a vehicle for Humphrey Bogart, Nobody Lives Forever benefits from Garfield's good looks, making the romantic twist a little more interesting. Jean Negulesco, better known for glossy romance than for noir, handles the material well, especially the climactic shootout.

Saturday, May 12, 2018

Air Force (Howard Hawks, 1943)

|

| John Garfield, George Tobias, and Harry Carey in Air Force |

Lt. Williams: Gig Young

Lt. McMartin: Arthur Kennedy

Lt. Hauser: Charles Drake

Sgt. White: Harry Carey

Cpl. Weinberg: George Tobias

Cpl. Peterson: Ward Wood

Pvt. Chester: Ray Montgomery

Sgt. Winocki: John Garfield

Lt. "Tex" Rader: James Brown

Maj. Mallory: Stanley Ridges

Col. Blake: Moroni Olsen

Susan McMartin: Faye Emerson

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: Dudley Nichols

Cinematography: James Wong Howe

Art direction: John Hughes

Film editing: George Amy

Music: Franz Waxman

"Fried Jap coming down!" crows gunner Weinberg as a Japanese fighter pilot and his plane attacking the Mary-Ann are consumed in flames. It's a much-quoted and much-parodied line that puts Howard Hawks's Air Force squarely where it belongs: in the wounded jingoism of the period immediately post Pearl Harbor. We wince at the line today, but Air Force has endured not so much because it's a period piece as because it's a tremendously effective piece of filmmaking. Hawks, who was a licensed pilot and had served in the Army Air Corps during World War I, was the exactly right person to make the film, which producer Hal B. Wallis put into production shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and which he wanted to release on the first anniversary of the attack in 1942. Hawks was too savvy and persistent a craftsman to allow anything like an arbitrary deadline to hinder him, and his failure to adhere to Wallis's schedule led to a brief replacement as director by Vincent Sherman. Wallis was exasperated in particular by Hawks's constant departure from the producer-approved screenplay, particularly the dialogue. Nevertheless, Hawks persisted, and called in William Faulkner to rewrite Concannon's death scene, which the director found too saccharine. The result is one of the most affecting moments of the film. The rest is pretty much razzle-dazzle heroism and entertaining male-bonding: There's no Hawksian woman in the movie to take the guys down a peg, although Faye Emerson's bit as McMartin's sister and Williams's girlfriend has a good deal of the Hawksian tough cookie about her. Hawks wanted the film to be a wartime version of his great movie about pilots, Only Angels Have Wings (1939), but the propagandist pressures to support the war effort, and probably a good deal of meddling from Wallis and Warner Bros., kept him from achieving that goal. Still, the action is exciting and the performances are good, especially John Garfield as the reluctantly heroic Winocki and Harry Carey as the oldtimer mechanic -- though Carey, in his mid-60s, was probably more of an oldtimer than the role strictly calls for.

Monday, February 5, 2018

Force of Evil (Abraham Polonsky, 1948)

|

| John Garfield in Force of Evil |

Leo Morse: Thomas Gomez

Doris Lowry: Beatrice Pearson

Freddie Bauer: Howland Chamberlain

Ben Tucker: Roy Roberts

Edna Tucker: Marie Windsor

Bill Ficco: Paul Fix

Detective Egan: Barry Kelley

Hobe Wheelock: Paul McVeigh

Wally: Stanley Prager

Director: Abraham Polonsky

Screenplay: Abraham Polonsky, Ira Wolfert

Based on a novel by Ira Wolfert

Cinematography: George Barnes

Art direction: Richard Day

Film editing: Art Seid

Music: David Raksin

John Garfield was one of the few movie stars who could play leading man to Joan Crawford and Lana Turner, and then turn around and appear in a gritty drama like Force of Evil without letting his star power outshine the supporting cast of character actors and unknowns. In Abraham Polonsky's film, he's a lawyer connected to the big players in the numbers racket, an illegal lottery that flourished before the legal ones took over. Joe Morse is torn in two directions: his work for the gangster Ben Tucker, who wants to take over the numbers game from the smaller "banks" that work in New York City neighborhoods, and his ties to his brother, Leo, who runs one of those banks. The numbers, posted in the daily newspapers, are based on the amount of bets placed on a day's horse races. Theoretically, the trio of numbers -- the last digits in the amount -- should be completely random. But Tucker has discovered a way to rig the numbers so that they'll come up 776 on Independence Day -- a day when a lot of bettors choose that number -- thereby causing a lot of the banks to go bust. When Joe learns of the scheme, he tries to tip off Leo, but his brother is having none of it. Joe also becomes involved with one of Leo's employees, Doris Lowry, who is grateful to Leo for having given her a job when she first came to New York, but now wishes to quit the shady business. Beatrice Pearson, who made her debut in the film but gave up movies for the stage, is a fresh and engaging presence, making the "love interest" feel less obligatory than it might. Garfield, of course, is terrific in one of his best roles, striking the right note of moral corruption while still retaining an essential attractiveness. George Barnes's cinematography is superb, whether he's working with Richard Day's sets or New York City locations. There's a haunting shot of Joe Morse in a deserted Wall Street, and the film's emotional climax is Joe's descent to the river beneath the George Washington Bridge to find where his brother's body has been dumped. Force of Evil is a downer, but a surprising one, and it makes one feel all the more bitter about the damage that the blacklist did to Polonsky and to Garfield, whose persecution by the commie-hunters may have contributed to his early death.

Thursday, June 8, 2017

Humoresque (Jean Negulesco, 1946)

|

| John Garfield and Joan Crawford in Humoresque |

Paul Boray: John Garfield

Sid Jeffers: Oscar Levant

Rudy Boray: J. Carrol Naish

Esther Boray: Ruth Nelson

Gina: Joan Chandler

Phil Boray: Tom D'Andrea

Florence Boray: Peggy Knudsen

Monte Loeffler: Craig Stevens

Victor Wright: Paul Cavanagh

Frederick Bauer: Richard Gaines

Paul as a child: Robert Blake

Director: Jean Negulesco

Screenplay: Clifford Odets, Zachary Gold

Based on a story by Fannie Hurst

Cinematography: Ernest Haller

Art direction: Hugh Reticker

Film editing: Rudi Fehr

Music: Franz Waxman

Jean Negulesco's Humoresque gets its title from the Fannie Hurst short story it's based on, but it also evokes the music played behind the opening title: the seventh of Antonín Dvořák's Humoresques, a group of short piano pieces that were later transcribed for orchestra. The music is best known today for the several facetious lyrics that have been attached to it, including "Passengers will please refrain from flushing toilets while the train is standing in the station" and "Mabel, Mabel, strong and able, get your elbows off the table."* Today, the movie also inspires similar irreverence, as an example of the melodramatic excesses of Joan Crawford's later career. How many drag queens have donned replicas of the Adrian gowns Crawford wears in the film, with shoulder pads so wide and sharp you fear that she could injure a bystander with a sudden turn? But there are far worse movies than Humoresque, and far less impressive performances than Crawford's in it. She doesn't appear until well into the film, after we've established the ruthless desire of Paul Boray to become a famous concert violinist. All he needs, it seems, is a rich patron, so when he meets Helen Wright, who has the money and nothing else to do with it but take lovers and drink, his fate is sealed. It's not like he doesn't have people to warn him off: There's his fellow musician, pianist Sid Jeffers, who can't supply much more than cynical wisecracks to keep Paul from doing the wrong thing. And there's his mother, who bought him his first violin but now wants him to settle down with fellow starving musician Gina and raise a family. But once Paul falls into Helen's clutches and becomes a hugely successful concert artist, all Mama and Gina can do is sit in the audience and glare up at Helen in her box -- though Gina sometimes bursts into tears and flees the auditorium. None of this would work if Garfield and Crawford didn't play their roles as well as they do. Garfield brings all the intensity and conviction to Paul that he does to his ambitious boxer in Body and Soul (Robert Rossen, 1947). Although the violin playing is actually done by Isaac Stern, with some nice camera trickery that puts Garfield's face and Stern's fingers in the same frame, Garfield keeps up the illusion well, to the extent of busily working the fingers on his left hand, practicing the fingering even when he's not playing. He has some improbable lines to speak -- the screenplay by Clifford Odets and Zachary Gold is freighted with them -- but he makes them work. As for Crawford, ambition was her nature and ruthlessness her forte in life as well as art, but she never just speaks her lines -- she inhabits them. There's no surprise in her performance, but that's not what we want from her. Negulesco's direction can be a little shapeless -- there's a gratuitous mid-film montage depicting a busy, hyped-up New York City -- but he handles the concluding sequence, set to a pastiche of themes from Tristan und Isolde, very well. Franz Waxman received an Oscar nomination for scoring, and there are excerpts from composers like Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Bizet, Mendelssohn, and Bach throughout: The film is a reminder that there was once a time when the audience for a Hollywood film would sit through extended passages of classical music.

*Or in my case, the discovery along with generations of other English lit grad students that the pouncing trochees of Tennyson's "Locksley Hall" -- e.g., "In the spring a young man's fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love" -- could be sung to Humoresque No. 7.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

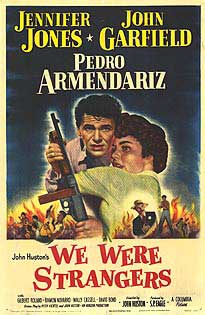

We Were Strangers (John Huston, 1949)

Fidel Castro, who died this year, came to power in 1959, ten years after We Were Strangers, which deals with an earlier Cuban revolution, was made. Castro's own revolution is probably why this film, despite its major director and stars, is so little known. It was never revived after its initial showing, and didn't become available on video until 2005 despite the reputation of its director, John Huston. It's a fairly scathing look at the failure of the United States to support the overthrow of the Machado dictatorship in 1933. John Garfield plays Tony Fenner, a Cuban-born American who works with the underground revolutionaries to overthrow Machado. He comes up with a rather complicated plot to tunnel into the Colón Cemetery and plant a bomb that will kill the regime's leaders. He enlists a group who have no previous ties with one another, including China Valdés (Jennifer Jones), a bank clerk whose brother was killed by the Havana police chief, Armando Aréte (Pedro Armendáriz), and who lives in a house across the street from the cemetery. The plan is to assassinate a high-ranking member of the regime and detonate the bomb when the dignitaries gather for his funeral. But Fenner's plan is just a little too complicated, and things go awry. It's a curious film to be made just as the red scare was heating up in Washington and Hollywood, for the script by Peter Viertel and director John Huston has no scruples about portraying the violent revolutionaries as heroic. The revolutionaries even countenance the collateral damage of killing innocent people at the funeral, although one of their company has serious reservations about it and, worn down by the hard work of tunneling, goes mad. Garfield, who would soon be threatened with blacklisting as a leftist, gives a typically intense performance, and Jones, though miscast, does a passable imitation of a determined Cuban revolutionary. Armendáriz, whom Hollywood often relegated to Latino sidekick roles, is a fine, sinister villain. Gilbert Roland, as a singing, wisecracking member of the revolutionary team, provides what levity the film possesses, and Ramon Novarro has a cameo as the chief who authorizes Fenner's plan. There's some obvious use of rear projection in which the actors are superimposed against scenes actually filmed in Havana, but Russell Metty's cinematography is mostly quite effective.

Friday, April 29, 2016

Body and Soul (Robert Rossen, 1947)

Body and Soul is a well-made boxing picture, but it has a historical significance as the nexus of some major careers damaged by the anti-communist hysteria that gripped the United States in the years that followed its release. After its director, Robert Rossen, pleaded the fifth amendment at his hearing before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951, he was blacklisted in Hollywood. The same fate befell screenwriter Abraham Polonsky after his refusal to testify before HUAC. The star, John Garfield, testified that he knew nothing about communist activity in Hollywood, but studios refused to hire him; he made his last film in 1951 and died of a heart attack the following year, only 39. Cast members Anne Revere, Lloyd Gough, Canada Lee, and Art Smith were also victims of the blacklist. The film stands as an example of the folly of HUAC witch-hunting: With all the reds and pinkos involved in its production, you might expect it to be pure propaganda, but the only leftist message it communicates is about the danger of greed. Today the only viewers who may find Body and Soul subversively anti-capitalist are those who subscribe to the "greed is good" credo enunciated by Michael Douglas's Gordon Gekko in Wall Street (Oliver Stone, 1987). Garfield plays an ambitious young boxer named Charley* Davis who falls prey to racketeers who manipulate his career, despite the warnings of his mother (Revere), his best friend, Shorty (Joseph Pevney), and his girlfriend, Peg (Lilli Palmer). The fight sequences, shot by James Wong Howe and edited by Francis Lyon and Robert Parrish, were groundbreaking in their realistic violence, winning Oscars for Lyon and Parrish. Howe, who is said to have worn rollerskates and used a hand-held camera to film the fights, was curiously unnominated, but nominations also went to Garfield and Polonsky. Palmer, unable to conceal her German accent or to eliminate traces of the sophisticated roles she usually played, is miscast as Charley's artist girlfriend. The script makes a half-hearted attempt to explain away the accent but mostly ignores it. One thing of note: The black boxer played by Lee calls Garfield's character by his first name, Charley, in their scenes together. The usual racial protocol was for African-American characters to call white ones "Mr." -- "Mr. Charley" or "Mr. Davis" -- the way Dooley Wilson's Sam always refers to Bogart's character as "Mr. Rick" in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943). It's the earliest example of an assumed equality that I can recall in a Hollywood movie.

*A nitpicky note: The filmmakers never decided whether it was spelled "Charley" or "Charlie." It appears both ways on the posters advertising his fights, but it's "Charlie" in the inscription on a gift he gives Peg and in her letter addressed to him. I'm going with the way IMDb lists it.

*A nitpicky note: The filmmakers never decided whether it was spelled "Charley" or "Charlie." It appears both ways on the posters advertising his fights, but it's "Charlie" in the inscription on a gift he gives Peg and in her letter addressed to him. I'm going with the way IMDb lists it.

Wednesday, January 13, 2016

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946)

It's one of the most memorable entrances in movies. Actually, her lipstick enters first, rolling across the floor toward him. She is Cora Smith and he is Frank Chambers, the man her husband has just hired to work in their roadside café/filling station. But more important, she is Lana Turner, one of the last of the products of the resources of the studio star factories: lighting, hair, makeup, wardrobe, and especially public relations. And he is John Garfield, one of the first of a new generation of Hollywood leading men, trained on the stage, and with an urban ethnicity about him: His vaguely presidential nom de théâtre thinly disguises his birth name, Jacob Julius Garfinkle. The pairing shouldn't work: She's a goddess, not an actress, whom the publicists had turned into "the Sweater Girl" while claiming that she had been discovered at a drugstore soda fountain. He was the child of Ukrainian-born Jews and grew up on the Lower East Side, trained as a boxer and studied acting with various disciples of Stanislavsky. But the chemistry is there from the moment Frank picks up Cora's lipstick and the camera surveys her from toe to head: white shoes, tan legs, white shorts, tan midriff, white halter top, blond hair, white turban. She reaches out her hand for the lipstick, but he doesn't move, so she comes over and gets it. It's one of the many power plays that will take place between them. The rest is one of the great film noirs, from a studio that didn't usually make them, MGM. In fact, the studio head, Louis B. Mayer, hated it, which is always a good recommendation: He hated Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950), too. (Mayer's tastes ran to Jeanette MacDonald-Nelson Eddy operettas and the Andy Hardy series.) It's the only really memorable movie directed by Tay Garnett, so I suspect a lot of credit goes to the screenwriters, Niven Busch and Harry Ruskin, and to their source, James M. Cain's overheated novel. Cain also wrote the novels that were the basis of two other famous noirs: Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) and Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945), so the screenwriters and the director had some powerful examples to follow.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)