|

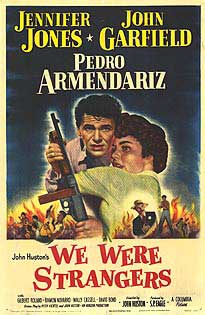

| Ramon Novarro, Cary Grant, Paula Raymond, and Leon Ames in Crisis |

Cast: Cary Grant, José Ferrer, Paula Raymond, Signe Hasso, Ramon Novarro, Gilbert Roland, Leon Ames. Screenplay: Richard Brooks, George Tabori. Cinematography: Ray June. Art direction: E. Preston Ames, Cedric Gibbons. Film editing: Robert Kern. Music: Miklós Rózsa.

In Crisis, Cary Grant plays a brain surgeon, which led one critic to snark that he looked like he should be holding a martini glass instead of a scalpel. That only points up the problem of movie star image: We expect Grant to be suave and wisecracking and not hung up on the dilemma of whether to perform an operation on a cruel dictator (José Ferrer) who is trying to fend off a revolution. Naturally, Grant's Dr. Ferguson sticks by the Hippocratic Oath and goes through with the operation. Meantime, unbeknownst to Dr. Ferguson, his wife (Paula Raymond) has been kidnapped and the revolutionaries are threatening to kill her if the dictator lives. Ferguson is unaware of this because the dictator's wife (Signe Hasso) has intercepted the message from the revolutionaries and destroyed it. It's a pretty good thriller premise, but writer-director Richard Brooks doesn't know how to build the suspense it needs. This was Brooks's first feature film as director, so we may want to cut him some slack. After all, he does a few things well, including a demonstration of brain surgery techniques that adds a little documentary realism to the film. To my eyes, Grant's performance is perfectly fine, and Ferrer and Hasso know how to play villains. Raymond is a little bland as the wife, but there are solid supporting performances from Ramon Novarro as a colonel backing up the dictator, Gilbert Roland as a leader of the revolutionaries, and Leon Ames as an oil company executive trying to remain neutral in the political conflict in this unnamed Latin American country so he can build a pipeline. It's the film's own neutrality -- dictators are bad, but revolutionaries can be, too -- that saps a good deal out of the drama.