|

| Myriam Cyr, Julian Sands, Gabriel Byrne, and Natasha Richardson in Gothic |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, March 31, 2024

Gothic (Ken Russell, 1986)

Wednesday, January 31, 2024

Whore (Ken Russell, 1991)

|

| Theresa Russell in Whore |

Cast: Theresa Russell, Benjamin Mouton, Antonio Fargas, Elizabeth Morehead, Daniel Quinn, Sanjay Chandani, Jason Saucier, Michael Crabtree, John Nance, Danny Trejo, John Diehl. Screenplay: Ken Russell, Deborah Dalton, based on a play by David Hines. Cinematography: Amir Mokri. Production design: Richard B. Lewis. Film editing: Brian Tagg. Music: Michael Gibbs.

The bluntness of its title suggests that Whore might be a serious film, a necessary corrective to the typical Hollywood treatment of prostitution, on a par with Lizzie Borden's 1986 Working Girls. And I think at some point that was its intent, especially with the hiring of a well-known actress like Theresa Russell. But in the hands of screenwriter-director Ken Russell, it turned into a bore, hammering home its message about the sordid lives of streetwalkers and their pimps, while giving it an entirely inappropriate glossy look. It also features an uncommonly bad performance by its star, who somehow can't find a way to deliver her lines that doesn't feel like a caricature of the tough girl she's supposed to be. The emotions she's meant to evoke feel fake. The screenplay, which forces her to talk directly to the camera, also undermines any sense of actuality to what she's saying. It's an 85-minute film that feels twice that length.

Thursday, January 18, 2024

Altered States (Ken Russell, 1980)

|

| William Hurt in Altered States |

Cast: William Hurt, Blair Brown, Bob Balaban, Charles Haid, Thaao Penghlis, Miguel Godreau, Dori Brenner, Peter Brandon, Charles White-Eagle, Drew Barrymore, Megan Jeffers. Screenplay: Paddy Chayefsky, based on his novel. Cinematography: Jordan Cronenweth. Production design: Richard Macdonald. Film editing: Eric Jenkins. Music: John Corigliano.

In theory, choosing Ken Russell to direct Paddy Chayefsky's screenplay based on his novel, an updating of Robert Louis Stevenson's 1886 novella Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to the psychedelic era, had some potential. Russell is known for his flamboyant visuals and Chayefsky for his talky screenplays like the Oscar-winning Marty (Delbert Mann, 1955), The Hospital (Arthur Hiller, 1971), and Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976). Perhaps the visuals would moderate the verbosity, or vice versa. Unfortunately, Altered States wound up something of a mess -- a watchable mess, but still not a satisfying film. Chayefsky was so upset with the movie he took his name off the credits and substituted a pseudonym, Sidney Aaron. But the problem is inherent in the premise: that a potion can alter not only the mental state of the person who takes it but also the physical state -- that matter itself, the human body, can be changed by drinking a mixture of blood and hallucinogenic mushrooms. It's the stuff of fairy tales, not science. So when Dr. Jessup (William Hurt in his film debut), a respected physician researching the causes of schizophrenia, drinks the concoction, he reverts to his primordial self: a small, aggressive carnivorous simian. Good enough for a horror-movie setup, but not quite what Chayefsky had in mind when he wrote lines like these: "It is the Self, the individual mind, that contains immortality and ultimate truth.... Ever since we dispensed with God we've got nothing but ourselves to explain this meaningless horror of life." Chayefsky's existential conundrums go missing in a welter of special effects. And ultimately, the film collapses in bathos, with a plot resolution in which love conquers all after Jessup's experiments go calamitously awry. Hurt and Blair Brown as Jessup's wife do what they can with the material, giving controlled performances, but Russell, that connoisseur of excess, lets Charles Haid overplay his role as Dr. Parrish, the supposed skeptic about Jessup's research who seems like a nutcase himself.

Thursday, January 11, 2024

The Boy Friend (Ken Russell, 1971)

|

| Christopher Gable and Twiggy in The Boy Friend |

Cast: Twiggy, Christopher Gable, Max Adrian, Bryan Pringle, Murray Melvin, Moyra Fraser, Georgina Hale, Sally Bryant, Vladek Sheybal, Tommy Tune, Brian Murphy, Graham Armitage, Antonia Ellis, Caryl Little, Glenda Jackson. Screenplay: Ken Russell, based on a musical play by Sandy Wilson. Cinematography: David Watkin. Production design: Tony Walton. Costume design: Shirley Russell. Music: Peter Maxwell Davies; songs: Sandy Wilson, Nacio Herb Brown, Arthur Freed.

Nothing succeeds like excess. That seems to have been Ken Russell's motto, well displayed in The Boy Friend. As I watched it, I thought the first parody of Busby Berkeley's kaleidoscopic production numbers for Warner Bros. musicals was brilliant. The second was entertaining. The third was ... well, maybe the law of diminishing returns had set in. The original stage musical was a campy sendup of the kind of musical comedies that P.G. Wodehouse, Guy Bolton, and Jerome Kern used to create for the Princess Theatre and later in the 1920s: tuneful light romances with silly plots. But for the movie, Russell superadds a campy sendup of the backstage movie musicals of the 1930s, borrowing plot and even dialogue from 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933), hence the Berkeley parodies. I first saw The Boy Friend around the time of its first release, and enjoyed it. But watching it again now, I found myself looking at the clock after the first hour and a half passed. The version I had seen in the theater was the one MGM had cut by 25 minutes; the restored version runs an exhausting two hours and 17 minutes. That said, there is much to enjoy about Russell's movie, especially the vividly colored production design by Tony Walton and costumes by Shirley Russell (the director's wife). The presence of the great Tommy Tune in the cast is also a plus. The Sandy Wilson songs are pleasantly hummable, and the interpolation of two songs by Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed that were featured in Singin' in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952) is nice. But a little camp goes a long way, and piling camp on camp can be tiresome, especially if the camp is done the way Russell does it: with a smirk rather than a wink.

Tuesday, October 22, 2019

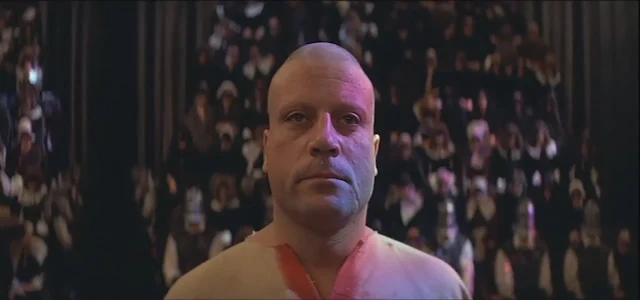

The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

Cast: Oliver Reed, Vanessa Redgrave, Gemma Jones, Dudley Sutton, Max Adrian, Murray Melvin, Michael Gothard, Georgina Hale, Christopher Logue, Graham Armitage, Brian Murphy, John Woodvine, Andrew Faulds, Kenneth Colley, Judith Paris, Catherine Willmer, Izabella Telezynska. Screenplay: Ken Russell, based on a play by John Whiting and a novel by Aldous Huxley. Cinematography: David Watkin. Production design: Derek Jarman. Film editing: Michael Bradsell. Music: Peter Maxwell Davies.

Oliver Reed, the bad boy of British movies of the 1960s and '70s, seems an odd choice as the hero of The Devils, Urbain Grandier, the "hot priest" who inspires lust in an entire nunnery but also goes to the stake as a martyr to the cause of individual and religious freedom. He also gives the most controlled performance in a film in which everyone goes well over the top, including Vanessa Redgrave, who does a lot of seething and writhing as Sister Jeanne, the hunchbacked prioress of said nunnery. Glenda Jackson was originally thought of for the role, but turned it down because she didn't want to play another madwoman after Peter Brook's Marat/Sade (1967) and Russell's The Music Lovers (1971). I tend to sympathize with her: The Devils became a cause célèbre when the censors took offense at its nudity and supposed blasphemy, earning it an X rating in the United States and Britain, but today, when it would receive only a rather stern R, it feels more like the product of a director given to a kind of adolescent excess. There's a smirkiness in Russell's approach to what purports, in an opening title, to be a true story drawn from historical documentation. David Thomson has said that Russell "is oblivious of his own vulgarity and the triteness of his morbid misanthropy," which is taking it a bit further than I would. I think instead that Russell celebrates vulgarity, but not with any sense of irony about it, to the point that the luridness of The Devils becomes boring.