|

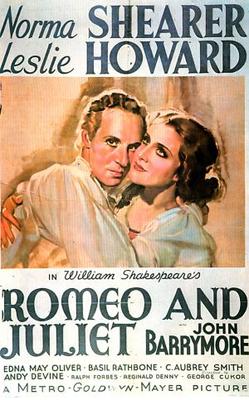

| Ann Harding, Leslie Howard, and Myrna Loy in The Animal Kingdom |

The odd, arch, talky The Animal Kingdom is based on one of Philip Barry's plays about rich people yearning to be free, like his Holiday and The Philadelphia Story, film versions of which were directed by George Cukor in 1938 and 1940 respectively. And here the connection among the films gets more intricate, for the director of The Animal Kingdom, Edward H. Griffith, had directed an earlier film version of Holiday in 1930, also starring Ann Harding, with a screenplay by Horace Jackson. And Cukor was an uncredited co-director on The Animal Kingdom. Moreover, the 1932 stage version had starred Leslie Howard, as well as William Gargan and Ilka Chase. So maybe everybody concerned with filming The Animal Kingdom was a little too close to the material, because the movie is a bit of a mess. The central love triangle -- Daisy Sage (Harding) is the former mistress of Tom Collier (Howard) who plans to marry Cecelia Henry (Myrna Loy) just as Daisy comes back into his life -- is clear enough, but the movie is cluttered with secondary characters whose function in the lives of the central characters is a bit obscure, as if their backstories were more interesting than what we actually see on the screen. Tom, for example, has a butler named Regan (William Gargan) who is an ex-boxer completely unsuited to his duties as butler, which causes tensions with Cecelia. What Tom and Regan's obligations to each other are based on remains unknown. Daisy similarly has a friend named Franc (Leni Stengel), who plays the cello and speaks with a German accent, attributes that are obvious but of no significance to the plot. Still, there are some bright lines and some nice pre-Code naughtiness like a reference by Tom to a brothel he used to visit in London, not to mention the fact that the film is quite open about the relationship between Tom and Daisy: At one point she refers to herself as "a foolish virgin... Oh, foolish anyway," which is the kind of line no American movie could get away with for several decades after the 1934 Production Code went into effect. But I think I might have enjoyed The Animal Kingdom more if I didn't think it was radically miscast, that Loy should have played the somewhat free-spirited Daisy and Harding the more conventional Cecelia. In fact, this was a breakthrough role for Loy, who had been typecast as sultry, often "Oriental" women. In The Animal Kingdom, Loy comes across as sexy and Harding as bland, which is the reverse of the way it should be. Their pairing shows why Loy became a major star and Harding began to fade out of films in the mid-1930s. But both deserved better than this comedy of manners that's more mannered than comic.