Designed to show off the novelty of sound -- and, in two sequences, the coming novelty of Technicolor --

The Hollywood Revue of 1929 was enthusiastically received by critics and audiences, though it lost the best picture Oscar to

The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont, 1929). Today, both movies are creaky antiques, despite the effort that MGM put into producing them. In fact,

The Hollywood Revue often seems like an attempt to promote

The Broadway Melody, which had opened three and a half months earlier, since it gives prominent spots to that film's stars, Charles King, Bessie Love, and Anita Page. The rest of it feels a lot like amateur night at MGM, as the studio's stars are trotted out for songs and skits that often feel tired and incoherent. In a few years, MGM would be boasting that it had more stars than there are in heaven, but many of the stars showcased in the

Revue are forgotten today -- like King, Love, and Page -- or were on the wane -- like John Gilbert, Marion Davies, and Buster Keaton. The ones that remained stars, like Jack Benny and Joan Crawford, did so by reinventing themselves. The

Revue, which modeled itself on theatrical conventions like the minstrel show and vaudeville, both of which were on the outs, failed to break ground for the Hollywood musical: It would take a few years for Warner Bros. to do that, with

42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933) and the unfettered imagination of Busby Berkeley taking the backstage musical formula of

The Broadway Melody and some of Sammy Lee's choreographic tricks from the

Revue -- including overhead kaleidoscope shots -- and improving on them. The

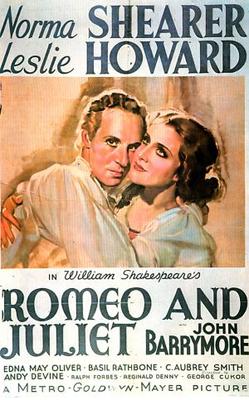

Revue has a few highlights even today: Joan Crawford trying a little too hard to sparkle as she sings (passably) and dances (clunkily); Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in their first sound film, doing a magic act with Jack Benny's intervention; Cliff Edwards and the Brox Sisters doing "Singin' in the Rain," which gets a Technicolor reprise with most of the company at the film's end; Keaton acrobatically clowning his way (silently) through an "underwater" drag routine; and Norma Shearer and John Gilbert in Technicolor performing a bit of the balcony scene from

Romeo and Juliet, first as Shakespeare wrote it and then in 1929's slang. To get to them, however, you have to sit through a lot of dud routines and dated songs like Charles King's paean to maternity, "Your Mother and Mine," which must have been aimed right at the mushy heart of Louis B. Mayer.

_poster.jpg)