Bad movies are often fun to watch anyway, and most of the people involved with The Chase, including director Arthur Penn, screenwriter Lillian Hellman, and star Marlon Brando, agreed that it was a bad movie. Brando let his opinion show, giving a sluggish performance that validates the old criticism that he mumbled his lines. Hellman had her script taken away and rewritten, and Penn struggled to deal with an ill-conceived project. The chief interest the film generates today is seeing actors like Jane Fonda, Robert Redford, and Robert Duvall on the brink of major stardom. There's a good deal of miscasting, including E.G. Mashall as the boss of a small town that seems to be in Texas or Louisiana. Marshall lacks the ruthless aura that the character needs. Angie Dickinson is wasted as the loving and dutiful wife of the town sheriff played by Brando. And Redford feels out of place in the role of Bubber Reeves, the town bad boy who escapes from prison (it's never quite clear what he did to be sent there) and stirs a manhunt, a lynch mob, and a conflagration in a junkyard. The town itself is a hotbed where everyone sleeps with everyone else's spouse and goes orgiastic on the Saturday night when the news of Bubber's escape breaks. It's a silly and lurid movie, but a little too long to be entertainingly bad.

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Marlon Brando. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Marlon Brando. Show all posts

Friday, July 26, 2024

The Chase (Arthur Penn, 1966)

Cast: Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda, Robert Redford, E.G. Marshall, Angie Dickinson, Janice Rule, Miriam Hopkins, Martha Hyer, Richard Bradford, Robert Duvall, James Fox, Diana Hyland, Henry Hull, Jocelyn Brando. Screenplay: Lillian Hellman, based on a novel by Horton Foote. Cinematography: Joseph LaShelle. Production design: Richard Day. Film editing: Gene Milford. Music: John Barry.

Sunday, July 12, 2020

The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1953)

|

| Mary Murphy and Marlon Brando in The Wild One |

The best performance in The Wild One isn't Marlon Brando's, it's Lee Marvin as Chino, the head of a rival motorcycle gang. Marvin brings a looseness and wit to the role that is lacking in Brando's performance, though the role itself calls on Brando to do little but act sullen. He also looks a little porky in his jeans and leather jacket, and his somewhat high-pitched voice gives an epicene quality to Johnny Strabler, leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. Brando does, however, get the film's most familiar line: When Johnny is asked what he's rebelling against, he's drumming to the beat of the music on the jukebox and retorts, "What've you got?" But it's a measure of the general mediocrity of The Wild One that this exchange is immediately reprised by someone telling others about Johnny's retort, essentially stepping on the line. There are a few good moments in the film, mostly contributed by Marvin and by some effective choreography of the motorcycle riders, as in the scene in which good girl Kathie Bleeker (Mary Murphy) is menaced by the gang and then rescued by Johnny. But censorship sapped the life out of the film: The motorcycle gangs are scarcely more intimidating than fraternity boys on a spree. There's an attempt to spice things up with a scene between Johnny and Britches (Yvonne Doughty), a female hanger-on with the rival gang, suggesting that they once had something going on, but the bit goes nowhere and seems mainly designed to allow the actress to display her perky breasts in a tight sweater. As with any of the countless biker movies that capitalized on the box office success of The Wild One, there's a queer subtext to be explicated in all this male bonding, but it doesn't add much to a movie that now seems as dated as the flaming youth films of the 1920s.

Saturday, February 29, 2020

A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951)

|

| Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh in A Streetcar Named Desire |

A great American play with a great mostly American cast. Well, three quarters American isn't bad, if the British fourth quarter of the cast is Vivien Leigh, who gives one of the great screen performances, turning Blanche Dubois into a brilliant sparring partner for Marlon Brando's Stanley Kowalski. But each time I watch the film, I am drawn more and more to Kim Hunter's Stella, who has the difficult role of mediator between Blanche and Stanley. Hunter also superbly captures why Stella is so doggedly faithful to the brutal Stanley, a matter that may trouble us more in an age of heightened consciousness of domestic violence. Stella is deeply, carnally in love with the brute, but also aware of the tormented boy within him. There's no more telling scene than the morning after Stanley, in the notorious torn T-shirt, stands at the foot of the stairs bellowing "Stella!" and bringing her down from her retreat. Hunter demonstrates a full measure of post-coital bliss, looking as rumpled as the bed in which she's lying when Blanche arrives to waken her and is shocked by Stella's about-face. That's why, although the censors tried to eliminate any sense that Stella had forgiven Stanley at the end of the film, we know full well that she'll return to him. For the most part, the avoidance of the censors' strictures is deft, but they do eliminate some of the meaning of the rape scene -- that Stanley's only way to get the upper hand in the power struggle with Blanche is purely physical -- and they turn the ending of the film into somewhat of a dramatic muddle. If it's not a great movie, it's because the play, like most plays, was never intended to be a film. But it's still a great pleasure to hear these actors speaking some of the most potent lines ever written for the theater.

Sunday, December 11, 2016

Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

|

| Martin Sheen in Apocalypse Now |

Col. Kurtz: Marlon Brando

Lt. Col. Kilgore: Robert Duvall

Jay "Chef" Hicks: Frederic Forrest

Lance B. Johnson: Sam Bottoms

Tyrone "Clean" Miller: Laurence Fishburne

Chief Phillips: Albert Hall

Col Lucas: Harrison Ford

Photojournalist: Dennis Hopper

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Screenplay: John Milius, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Herr

Based on a novel by Joseph Conrad

Cinematography: Vittorio Storaro

Production design: Dean Tavoularis

Film editing: Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch

The familiar story of the confused and sometimes disastrous making of Apocalypse Now has been told many times, and never better than by Francis Ford Coppola's wife, Eleanor, in her 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse. So it's not worth going into here, except to note that the subtitle of her film plays on both the current meaning of the word "apocalypse" -- i.e., a disaster of great magnitude -- and the original one: a disclosure or revelation. It might be said that the enormous expenditure and hardship that Francis Coppola experienced during the making of Apocalypse Now was revelatory, not only to Coppola but also to the film industry, which was reaching the limits of its tolerance of unconstrained visionary filmmaking. It would cross that limit the following year with Heaven's Gate, Michael Cimino's film that took down a venerable production force, United Artists, along with its director. Coppola's career, unlike Cimino's, would recover, but he would never again be the director he was in his prime, with the first two Godfather films. And American filmmaking would never again be as prone to take risks as it was in the 1970s. As for the film itself, Apocalypse Now remains one of the essential American movies if only because it epitomizes the nightmare that was the Vietnam War. Coppola deserves much of the credit for this embodiment of Lord Acton's familiar dictum: "Power tends to corrupt. Absolute power corrupts absolutely." But there are others who should share the credit with him, including screenwriters John Milius and Michael Herr, who made the connection between Joseph Conrad's tale of imperialism gone wrong, Heart of Darkness, and the war. The ambience of the film is largely the work of production designer Dean Tavoularis, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who won a well-deserved Oscar, and Walter Murch and his sound team, who also won. And while Marlon Brando's Kurtz is a disappointment and Martin Sheen never quite meets the demands of his role as Capt. Willard, they are surrounded by marvelous support from Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Dennis Hopper, and a very young and almost unrecognizable Laurence Fishburne (billed as Larry), among others.

Friday, July 15, 2016

Julius Caesar (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1953)

Julius Caesar is the starchiest of Shakespeare's major plays, the one with the least sex, which is why many of us first encounter it in a high school English class. It's a play about soldiers and politicians, professions from which women were (unless they were Queen Elizabeth) excluded in Shakespeare's time, so there are only two female roles: Brutus's wife, Portia, and Caesar's wife, Calpurnia, and both of them are almost walk-ons. (My high school drama teacher wanted to stage Julius Caesar as our class play until he realized that three times as many girls as boys wanted to try out for parts.) So the remarkable thing about MGM's all-star production is that it turned out so well: It's one of the best Hollywood productions of Shakespeare. (Calpurnia and Portia are lavishly cast with Greer Garson and Deborah Kerr, respectively, in the small roles.) That said, it's a shame that not quite enough was done to take the starch out of the play. The casting of Marlon Brando as Mark Antony was a start, but although it's a very good performance, it tends to throw the film out of whack. When it was released, Brando had been stereotyped as a "Method mumbler," for his celebrated performance on stage and screen as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951). Could he rise to the demands of speaking Shakespearean diction? critics burbled. Of course he could, with a little bit of coaching from his distinguished co-star John Gielgud, who plays Cassius, and who was so impressed that he wanted Brando to go to London where he would direct him in Hamlet. That, of course, never took place, more's the pity. But the attention directed at Brando does tend to shift the focus away from the real central character of the play, Brutus, played with exceptional distinction by James Mason. Gielgud is also very good, although it seems to me that in the first part of the film he is a bit too stagy. Mason gives a kind of colloquial spin to his lines -- a sense that he's speaking what Brutus thinks and feels, and not reciting Shakespearean verse. Later in the film, when Brutus and Cassius go to war against Antony, Gielgud has loosened up more. Mankiewicz's adaptation of the play is solid, and he does smart things with camera placement -- putting the camera in the middle of the crowd, for example, when Brutus and Antony give their great speeches after Caesar's (Louis Calhern) assassination. But there is a kind of Hollywood Rome quality to the film -- not surprising, since it was made after the lavish MGM spectacle Quo Vadis (Mervyn LeRoy, 1951) and uses some of the same sets -- that tends toward the stodgy. That's more surprising when you realize that the producer of the film was John Houseman, who had also been a producer of Orson Welles's celebrated 1937 modern-dress Mercury Theatre production of the play, which created a sensation with its evocation of the rise of fascism in Italy and Germany.

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954)

Thursday, November 26, 2015

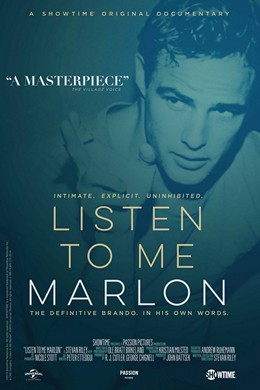

Listen to Me Marlon (Stevan Riley, 2015)

It's a truism that Marlon Brando revolutionized film acting. (With a little help from Montgomery Clift and James Dean, and some pioneering by John Garfield.) And it seems that Brando believed the truism himself: At one point in this fascinating documentary he disses such older film stars as Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, and Humphrey Bogart, asserting that they were always the same in their movies. This misses the point about film stardom, I think, which is that everyone who gets established as a film actor carries their image from movie to movie. How much variety, really, is there in Brando's most memorable film performances? Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951), Johnny Strabler in The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1953), Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954), and even Vito Corleone in The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) and Paul in Last Tango in Paris (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1972) are all troubled urban Americans with a rebellious streak. And when Brando tried to break away from that type -- as Emiliano Zapata in Viva Zapata! (1952), Mark Antony in Julius Caesar (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1953), Napoleon in Désirée (Henry Koster, 1954), or Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty (Lewis Milestone, 1962) -- the performances leave a lot to be desired. Mind you, I still think Brando was one of the greatest actors in film history, but only when he let himself play roles that suited him -- as Cooper, Gable, and Bogart did. This film, which uses Brando's own tape recordings as its principal source, shows him as a kind of tragic naïf in search of something that would heal the wounds he carried from childhood. He found it in acting when he fell under the spell of Stella Adler, although the Adler shown in this film is given to talking pretentious nonsense about how acting isn't about the words, it's about the soul. Brando also sought healing in sex, in psychoanalysis, in political activism, but the picture that emerges in the film is of a man who never succeeded in escaping his own tormented ego.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)