|

| Mary Murphy and Marlon Brando in The Wild One |

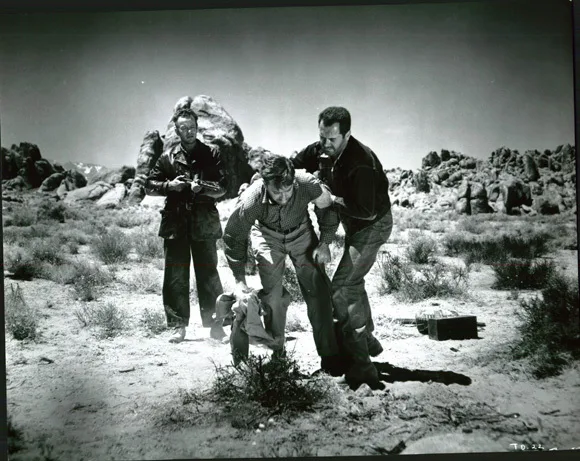

The best performance in The Wild One isn't Marlon Brando's, it's Lee Marvin as Chino, the head of a rival motorcycle gang. Marvin brings a looseness and wit to the role that is lacking in Brando's performance, though the role itself calls on Brando to do little but act sullen. He also looks a little porky in his jeans and leather jacket, and his somewhat high-pitched voice gives an epicene quality to Johnny Strabler, leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. Brando does, however, get the film's most familiar line: When Johnny is asked what he's rebelling against, he's drumming to the beat of the music on the jukebox and retorts, "What've you got?" But it's a measure of the general mediocrity of The Wild One that this exchange is immediately reprised by someone telling others about Johnny's retort, essentially stepping on the line. There are a few good moments in the film, mostly contributed by Marvin and by some effective choreography of the motorcycle riders, as in the scene in which good girl Kathie Bleeker (Mary Murphy) is menaced by the gang and then rescued by Johnny. But censorship sapped the life out of the film: The motorcycle gangs are scarcely more intimidating than fraternity boys on a spree. There's an attempt to spice things up with a scene between Johnny and Britches (Yvonne Doughty), a female hanger-on with the rival gang, suggesting that they once had something going on, but the bit goes nowhere and seems mainly designed to allow the actress to display her perky breasts in a tight sweater. As with any of the countless biker movies that capitalized on the box office success of The Wild One, there's a queer subtext to be explicated in all this male bonding, but it doesn't add much to a movie that now seems as dated as the flaming youth films of the 1920s.