|

| Pam Grier and Robert Forster in Jackie Brown |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Michael Keaton. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Michael Keaton. Show all posts

Tuesday, August 2, 2016

Jackie Brown (Quentin Tarantino, 1997)

Thursday, July 14, 2016

Spotlight (Tom McCarthy, 2015)

Considering that we spend half our waking lives at work, it's surprising that there are so few good films about what we do there. The problem may be that many, if not most, of the jobs we do lack the essential narrative shape: beginning, middle, and end. They're a routine repeating itself until death or retirement provides the closure. The exceptions would seem to be cops and doctors, who deal with life and death, and sometimes lawyers, if their jobs lead to the courtroom and aren't just an eternal drawing up of documents. But surprisingly, given the low esteem in which they're held by the general public, there are also some classic films about journalists at work; His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940) and All the President's Men (Alan J. Pakula, 1976) come immediately to mind. (I omit Orson Welles's magnum opus because it seems to me less about journalism than about obsession.) I will have to add Spotlight to the list, though despite its best picture Oscar (or maybe because of it) I think it's too soon to call it a great film. What makes it work for me is that it's a convincing portrait of what I know about journalists: that the good ones love what they do. Take Mike Rezendes, for example, whom I got to know a bit at the Mercury News. He's a few inches shorter and quite a few pounds lighter than Mark Ruffalo, who plays him in the movie, but what Ruffalo gets right about Rezendes is his absolute delight in doing the job right, flinging himself body and soul into his work. I would also single out here the performance of Liev Schreiber, one of our best and most underappreciated actors, whose Marty Baron is a spot-on portrait of the journalist who has found himself promoted upstairs to where his commitment to the profession is regarded with suspicion, even though his heart is in the right place. Michael Keaton's Walter Robinson is one of those who suspect Baron, and I wish there had been more scenes in which the growing confidence each has in the other was dramatized. John Slattery's Ben Bradlee Jr. is a keen portrayal of the journalist whose edges have been worn down to the point where he's always in danger of playing it too safe. Now, this judgment of the film is being made by someone who knows the territory, but considering how many cop movies seem ludicrous to cops, and how doctors tend to despise medical dramas, I think it speaks well of writer-director Tom McCarthy and his co-screenwriter Josh Singer that they manage to capture the essence of the journalism game (at least as it was in 2001-03, before the demise of newspapers) so extraordinarily well.

Thursday, April 7, 2016

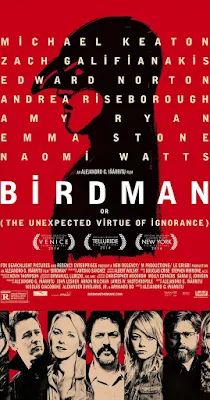

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)