|

| Joaquin Phoenix in Joker |

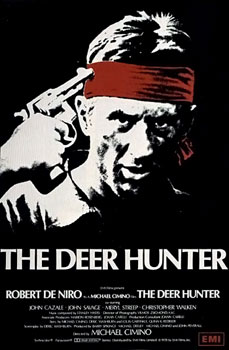

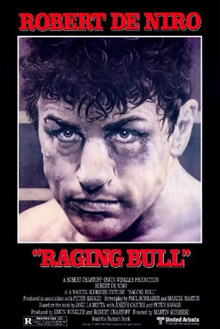

Todd Phillips's Joker is an unpleasant and occasionally clumsily made movie held together by Joaquin Phoenix's Oscar-winning characterization of the psychotic Arthur Fleck, who becomes at least one of the avatars of the Batman comics character called the Joker. But whatever its defects, Joker also seems to be very much of the moment -- the moment of post-Covid-19 civil unrest and societal divisions, abetted by corrupt and ineffective leadership. It's an ugly film about ugly attitudes, and although it strives to build a psychological explanation for Arthur Fleck's transformation into murderous, anarchic loner, the explanation is pat and clichéd. Phoenix is a great film actor, but to my mind he's much better in movies that call for humanity rather than monstrosity, like Spike Jonze's Her (2013) or James Gray's underrated We Own the Night (2007). Arthur Fleck is an Oscar-milking role, with grotesque body transformation and a plethora of overstated moments. Phillips's film calls for none of the dark humor that Heath Ledger gave his Joker in The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, 2008) or the entertaining flamboyance of Jack Nicholson's version of the character in Tim Burton's Batman (1989). Philips has modeled Arthur Fleck in part on two characters from Martin Scorsese's movies, Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976) and Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1982), and cheekily cast the man who played both, Robert De Niro, in his film. De Niro gives Phoenix someone his equal to play against, but echoing better movies is never a good idea. Zazie Beetz, a fine actress, is wasted in her role as the neighbor on whom Arthur develops an unsavory attraction, and Phillips muddles the revelation that their scenes together are mostly in Arthur's imagination. The denouement of the film is predictably cataclysmic, but Phillips flubs his ending scene of Arthur confined to the Arkham mental hospital by suggesting rather confusingly that he escapes -- presumably to set up a sequel -- and following it with Frank Sinatra's version of Steven Sondheim's "Send in the Clowns," a wistful song meant to be ironic in this context but really only thuddingly obvious, like much of the rest of the film.