Marius (Alexander Korda, 1931)

|

| Raimu and Pierre Fresnay in Marius |

César Olivier: Raimu

Marius: Pierre Fresnay

Honoré Panisse: Fernand Charpin

Fanny: Orane Demazis

Honorine Cabanis: Alida Rouffe

Félix Escartefigue: Paul Dullac

Albert Brun: Robert Vattier

Piquoiseau: Alexandre Mihalesco

Director: Alexander Korda

Screenplay: Marcel Pagnol

Based on a play by Marcel Pagnol

Cinematography: Theodore J. Pahle

Art direction: Alfred Junge, Vincent Korda

Fanny (Marc Allegret, 1932)

|

| Fernand Charpin, Raimu, Pierre Fresnay, and Orane Demazis in Fanny |

Cast identical to

Marius, except:

Félix Escartefigue: Auguste Mouriès

Aunt Claudine: Milly Mathis

Elzéar: Louis Boulle

Dr. Venelle: Édouard Delmont

Director: Marc Allegret

Screenplay: Marcel Pagnol

Based on a play by Marcel Pagnol

Cinematography: Nikolai Toporkoff

Production design: Gabriel Scognamillo

Music: Vincent Scotto

César (Marcel Pagnol, 1936)

|

| André Fouché and Raimu in César |

Cast identical to

Fanny, except:

Césariot: André Fouché

Félix Escartefigue: Paul Dullac

Innocent Mangiapan: Marcel Maupin

Elzéar: Thommeray

Pierre Dromard: Robert Bassac

Fernand: Doumel

Director: Marcel Pagnol

Screenplay: Marcel Pagnol

Cinematography: Willy Faktorovitch, Grischa, Roger Ledru

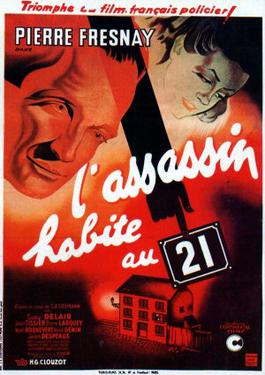

Critics of the auteur theory -- that the director is the true "author" of a film -- point to Marcel Pagnol's Marseille trilogy as a glowing exception: It's the writer's characters and dialogue that carry all three films, even when Pagnol himself is the credited director, as he is in the third film,

César. This amounts to nitpicking, I fear. Pagnol was on hand for all three films, even when they were nominally being directed by Alexander Korda and Marc Allegret (neither of them inconsiderable directors), and by all accounts Pagnol was not at all silent about making his opinions known. He had been an early enthusiast of the talkies, and immediately saw that his plays,

Marius and

Fanny, were naturals for the screen. What better way to sweeten his stories about life in Marseille than by opening them out with visuals of the actual waterfront? But for Pagnol, the words and the sounds came first: It's said that he would turn his back as a scene was being shot, and would only give his approval when what he heard sounded right. That presupposed, of course, a cast capable of making the words work, which meant starting with the original César, the actor known only as Raimu (Jules Auguste Muraire), and the original Panisse, Fernand Charpin, both of them born in the neighborhood of Marseille. The Marius, Pierre Fresnay, and the Fanny, Orane Demazis, had to be coached in the dialect, but most of the rest of the cast were from the south of France. The dialect is lost on us subtitle-dependent Anglophones, but it seems to have been one of the reasons that all of France took the trilogy to heart, relishing this slice of provincial life even in Paris. And it is a glorious trio of movies still, rich with comic performances, dominated of course by Raimu as the blustering, sentimental César. It's hard to find a performer to compare with Raimu, but the one that comes to my mind is Jackie Gleason as Ralph Kramden, certain of himself and capable of explosions that go off with lots of noise and very little actual damage. Raimu, Charpin, and the actors that form their little circle -- best seen when playing cards, as in the classic game in

Marius -- are a superb ensemble. There is some controversy over Demazis as Fanny -- the actress is described in one source as "pudding faced," and if you're expecting a gamine type like Leslie Caron, who played the part in the 1961

Fanny directed by Joshua Logan, you'll be disappointed. But I don't mind Demazis at all. While it's hard to think of her as the most beautiful girl in Marseille, she has the ability to pull off the more melodramatic scenes -- admittedly the weakest moments in the trilogy -- with real feeling. Pierre Fresnay is a touch too old in

Marius and

Fanny, but he comes into his own in

César, when the character is closest to his actual age. But what makes it work are the ebullient characters and the splendid comic timing of the performers.

Filmstruck Criterion Channel