|

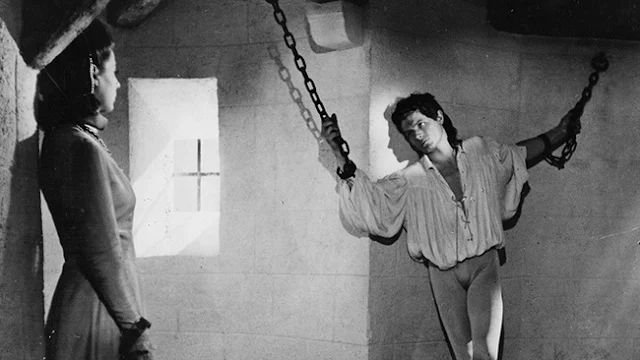

| Nathalie Nattier, Yves Montand, and Jean Vilar in Les Portes de la Nuit |

Malou: Nathalie Nattier

Georges: Pierre Brasseur

The Homeless Man: Jean Vilar

Guy Sénéchal: Serge Reggiani

M. Sénéchal: Saturnin Fabre

Raymond Lécuyer: Raymond Bussières

Claire Lécuyer: Sylvia Bataille

Cricri Lécuyer: Christian Simon

M. Quinquina: Julien Carette

Étiennette: Dany Robin

Étiennette's Boyfriend: Jean Maxime

Director: Marcel Carné

Screenplay: Jacques Prévert

Cinematography: Philippe Agostini

Production design: Alexandre Trauner

Film editing: Jean Feyte, Marthe Gottié

Music: Joseph Kosma

Marcel Carné's Les Portes de la Nuit was a flop in postwar France, and its poetically vague title may indicate some of the reasons why. The film attempts to walk a line between whimsy and tragedy, its vision of life in postwar Paris a little too suffused with romantic melancholy for audiences grappling with the day-to-day uncertainties of existence. The setting is February 1945, after the liberation of Paris but before the end of the war, a period that feels like a kind of limbo. A homeless man with the gift of foreseeing other people's fates walks through the streets, first encountering our protagonist, Jean Diego, a former member of the Resistance, on the Métro, Jean is going to see the wife of Raymond Lécuyer, a fellow Resistance fighter, to tell her that her husband is dead. But when he breaks the news, she bursts out laughing, whereupon the door opens to reveal a very much alive Lécuyer, who wants to know what's so funny. Jean, it turns out, had been captured along with Lécuyer and had overheard the orders sending him to the firing squad, but the execution didn't take place. Eventually, the plot will reveal who ratted on Lécuyer, and the homeless man will predict the rat's fate. But this story of the clash of Resistance and collaboration takes a secondary place in the film to the romance that develops between Jean and the beautiful Malou, the wife of Georges, who made his fortune in armaments during the war, as the film turns into a muddle of coincidences. Carné was a great director, and even this weakling among his films gives us something to watch, including a performance by the 25-year-old Yves Montand. He's a bit too young for the role, given that Jean was supposed to be a soldier of fortune before the war, but he was Carné's second choice after Jean Gabin, whom the director wanted to co-star with Marlene Dietrich as Malou. After starting to work with Carné, Gabin and Dietrich bowed out and went on to make Martin Roumagnac with Georges Lacombe instead -- not the most felicitous of choices. The other major distinction of Les Portes de la Nuit is the score by Joseph Kosma, which introduced his song "Les Feuilles Mortes," better known in the States as "Autumn Leaves," with lyrics by Johnny Mercer replacing the original ones by Jacques Prévert.