A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Theodor Sparkuhl. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Theodor Sparkuhl. Show all posts

Thursday, October 3, 2019

The Glass Key (Stuart Heisler, 1942)

The Glass Key (Stuart Heisler, 1942)

Cast: Alan Ladd, Brian Donlevy, Veronica Lake, William Bendix, Bonita Granville, Joseph Calleia, Richard Denning, Frances Gifford, Donald MacBride, Margaret Hayes, Moroni Olsen, Eddie Marr, Arthur Loft, George Meader. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on a novel by Dashiell Hammett. Cinematography: Theodor Sparkuhl. Art direction: Haldane Douglas, Hans Dreier. Film editing: Archie Marshek. Music: Victor Young, Walter Scharf.

There's something a little febrile about The Glass Key, and I don't just mean the movie -- it' s inherent in Dashiell Hammett's novel, too. The movie heightens it with the casting of Veronica Lake, who always seems a little out of it in her movies, on which she often clashed with directors and/or stars. And William Bendix's sadistic thug has a special menace for those of us who remember him in his familiar sitcom role, as the working-class schlub in The Life of Riley. It was a breakthrough role for Alan Ladd as the semi-conscientious right-hand man to Brian Donlevy's shady politician. Ladd gets beaten into the hospital by Bendix, where he spends a lot of time doing what he does best: flirting, in this case with the nurse. He also flirts with Lake, as the daughter of Donlevy's political rival turned ally, as well as with Bonita Granville, as Donlevy's sister, and even the wife of the corrupt newspaper publisher who wants to frame Donlevy for murder. And so on, in a reasonably faithful translation of Hammett's book that only misses the author's dryly tough prose style.

Tuesday, April 24, 2018

The Wildcat (Ernst Lubitsch, 1921)

|

| Pola Negri in The Wildcat |

Commandant of Fort Tossenstein: Victor Janson

Lt. Alexis: Paul Heidemann

Claudius: Wilhelm Diegelmann

Pepo: Hermann Thimig

Lilli: Edith Meller

Commandant's Wife: Marga Köhler

Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Screenplay: Hanns Kräly, Ernst Lubitsch

Cinematography: Theodor Sparkuhl

Art direction: Max Gronert, Ernst Stern

One of Ernst Lubitsch's last films made in Germany before he departed for Hollywood, The Wildcat, is subtitled A Grotesque in Four Acts, which is only mildly suggestive of its giddy absurdity. It doesn't resemble any other Lubitsch film I've seen, except in its uninhibited delight in playing with the medium. Pola Negri, usually cast in serious romances and initially burdened with a "femme fatale" label when she joined Lubitsch in Hollywood, here demonstrates a marvelous gift for knockabout comedy as the titular wildcat, the bandit's daughter who falls for a womanizing lieutenant and manages almost to bring an Alpine military fort to rubble. Working not only in actual snowy Alpine locations but also in some of the wackiest studio sets ever built, Lubitsch pulls out all the stops, using a mad variety of matte shots that frame the action at odd angles and in ridiculous compositions. The fort itself bristles with cannons from every corner, and its interiors are full of mad curlicues. The action is no less outlandish: At one point, the bandits breach the fort by using Negri as a kind of human battering ram. And when Negri's Rischka deserts her bandit husband to pursue the lieutenant, she returns to find a stream trickling out of their hut, created by the tears the bandit has shed. Sheer nonsense, but a kind of unknown classic of silent comedy, on a par with the work of Mack Sennett in its pioneering exploitation of the medium. Lubitsch would temper his imagination, but you can still see foreshadowings of the comedy tricks he would bring to less madcap work.

Saturday, January 28, 2017

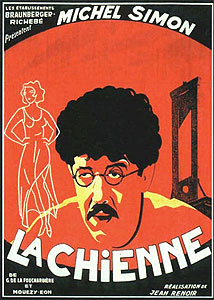

La Chienne (Jean Renoir, 1931)

Seeing Michel Simon as the milquetoast Maurice Legrand in La Chienne after L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934) and Boudu Saved From Drowning (Jean Renoir, 1932) is something of a revelation, even if at the end of La Chienne he has become something like Boudu. But the entire film is a revelation: The second sound film by Renoir, it demonstrates an innovative mastery of what was essentially a new medium, one that even the Americans who claimed to have invented synchronized sound were still struggling with. Renoir -- with the help of sound technicians Denise Batcheff and Marcel Courmes -- creates an auditory ambience still rare in 1931, relying on dialogue and sound effects created on set and not in post-production. The most often-cited example is the rasp of the paper knife held by Lulu (Janie Marèse) as she cuts the pages of the book she's trying to read -- just before Legrand kills her with it. But the film is full of small auditory details like the squeaking of the shoes worn by the defense attorney (Sylvain Itkine) as he paces nervously back and forth before his doomed client, Dédé (Georges Flamant). But beyond the technical mastery, which also includes some brilliant camerawork by cinematographer Theodor Sparkuhl, the film is a tour de force of bitter irony, not least because Renoir keeps it from falling into sensationalism or unrelieved darkness. Legrand, initially the henpecked husband to a termagant (Magdeleine Bérubet), brings calamity to several lives, not only those of Lulu and Dédé, but also those of his wife and her supposedly dead ex-husband (Roger Gaillard). And yet, at the film's end he survives, not only unbroken but in many ways a stronger man than he was at the film's beginning. His story is framed as a puppet show with, as a puppet claims, "no moral message." But though Legrand commits fraud, adultery, and murder without receiving the official punishment of the law, the moral is aimed at those who scorned and abused him: Beware the worm who may turn and prove to be a viper.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)