|

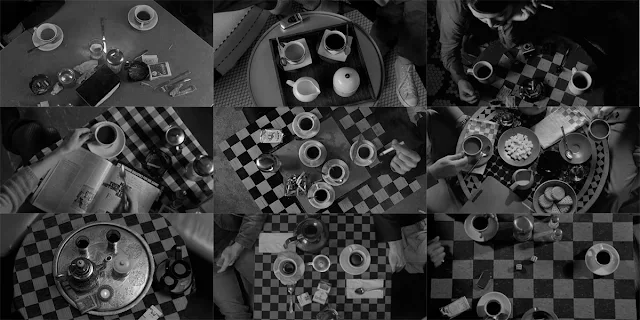

| Bill Murray and Adam Driver in The Dead Don't Die |

I suppose that having made a vampire movie, Only Lovers Left Alive (2013), Jim Jarmusch may have felt he had to make a zombie movie, but I wish he hadn't. The Dead Don't Die might have become a cult film if there weren't so many good Jarmusch films to choose from: It has all the earmarks of a guilty pleasure movie, like cheeky dialogue and a trendy horror movie trope, the zombie apocalypse. And I have to admit that it's not as bad as most of the zombie fare, and that it's not even Jarmusch's worst film -- I'd have to rank it above The Limits of Control (2009) for that dubious distinction. But there's something dispirited about it, a feeling that having latched onto the idea for the movie, Jarmusch grew bored with it. That reflects itself in the gimmick that gradually creeps into the film: that the cops Cliff (Bill Murray) and Ronnie (Adam Driver) know they're in a movie. It first surfaces when the song "The Dead Don't Die" keeps reappearing on the radio and Ronnie refers to it as "the theme song." Then, in the middle of some byplay between the two of them, Cliff asks, "What, are we improvising here?" And eventually, after Ronnie says, "Oh man, this isn't gonna end well" one time too many, Cliff objects, and Ronnie admits that he's read the script. Cliff is incredulous: "Jim only gave me the scenes I appear in," he fumes. These "meta" moments are amusing, but they counter any involvement a viewer might have in the fates of the characters, predictable as the genre makes them. Still, I liked some things in the film, especially Tilda Swinton's eerie undertaker, who speaks with a Scottish accent and wields a mean samurai sword. I still think Jarmusch is a wonderful writer-director -- Paterson (2016) was clear evidence that he hasn't lost his touch -- when he's got the right subject in mind, but I think he needs to edit himself more, and not just make movies when an idea strikes his fancy.

_poster.jpg)