|

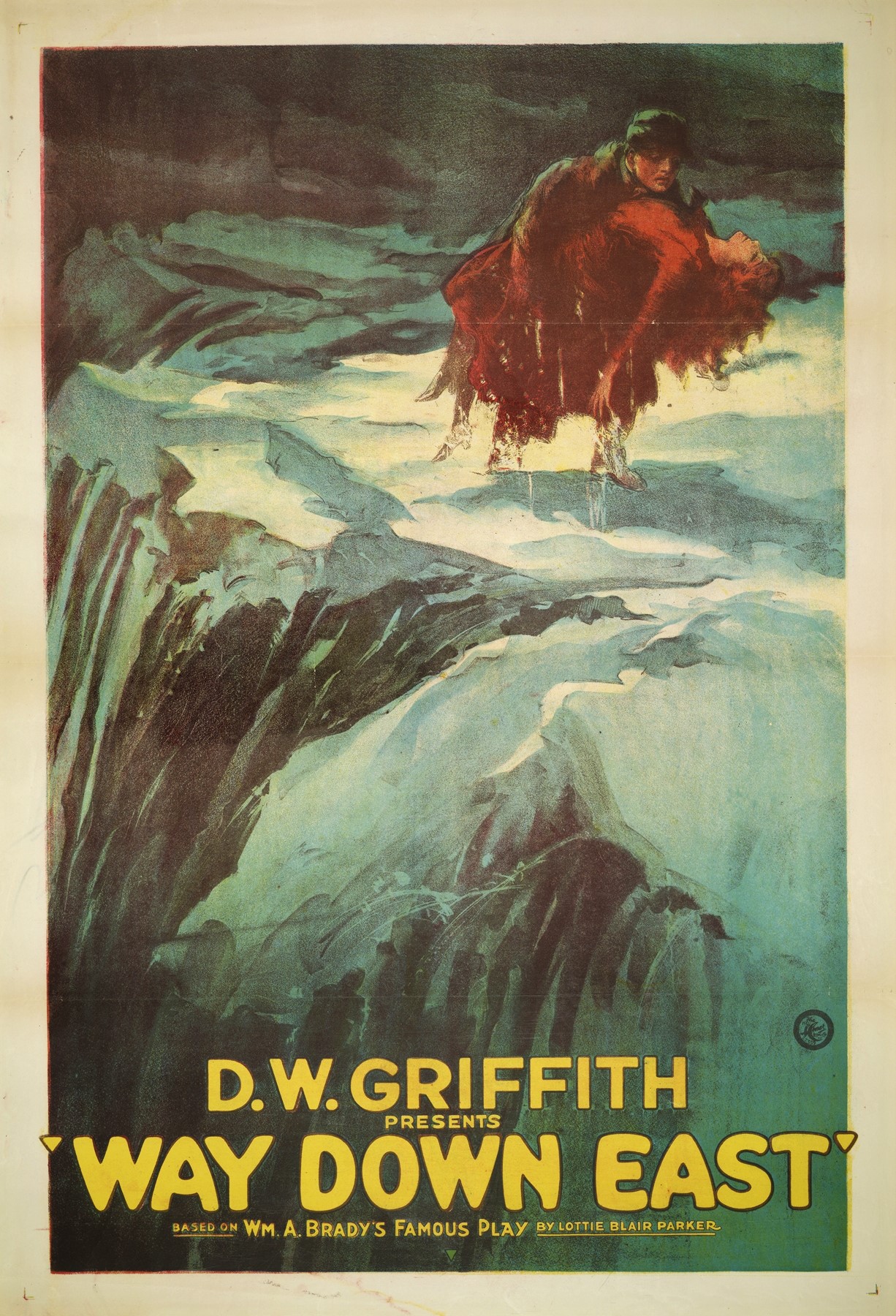

| Nikolay Burlyaev in Andrei Rublev |

Daniil Chyornyi: Nikolay Grinko

Theophanes the Greek: Nikolay Sergeyev

Boriska: Nikolay Burlyaev

Kirill: Ivan Lapikov

Durochka: Irma Raush

Prince Yuri/Prince Vasiliy: Yuriy Nazarov

Patrikei: Yuriy Nikilin

The Jester: Rolan Bykov

Foma: Mikhail Kononov

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Screenplay: Andrey Konchalovskiy, Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematography: Vadim Yusov

Production design: Evgeniy Chernyaev

Music: Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov

Has any filmmaker ever made more eloquent use of the widescreen format than Andrei Tarkovsky does in Andrei Rublev? It was a process developed by Hollywood to help win its war with television -- bigger naturally assumed to be better. In Hollywood, it usually went hand-in-hand with color, and although the various widescreen processes -- Cinerama, Cinemascope, VistaVision, etc. -- were used in black-and-white films, they often feel out of place today. A case in point: The Diary of Anne Frank (George Stevens, 1959), which won an Oscar for the cinematography of William C. Mellor, but which seems to cry out for a format less expansive than CinemaScope, in which the Frank family's attic seems far too spacious. Andrei Rublev was filmed in a process called Sovscope, which like CinemaScope used anamorphic lenses to produce a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Tarkovsky and cinematographer Vadim Yusov artfully work with the expanse of the screen, not shying away from closeups but also doing extraordinary movement with the camera. One of the earliest scenes takes place in the barn in which Rublev and his fellow artist-monks take shelter from the rain. We are given an astonishing 360-degree pan inside the barn, circling from the monks to the other denizens of the shelter and back to the monks, a study in faces that establishes one of the film's major subjects: the nature of Russian humanity, which also becomes an abiding concern of Rublev's. (I think there's a witty acknowledgment of the nature of widescreen in that the peep-hole cut into the wall of the bar seems to have the same aspect ratio as the film.) And in the concluding sequence, there is a magnificent pan from the gates of the walled city of Vladimir below and the emerging procession up to the structure that holds the newly cast bell, where Boriska waits anxiously. Andrei Rublev is one of those films I can't help rewatching; even though (or perhaps because) it's slow and challenging, it more than repays frequent viewings. Tarkovsky is not a director to be taken lightly, and the moment you begin to be lulled by the magnificence of Yusov's cinematography or Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov's score, the director is likely to shock you with images of cruelty and brutality but also of beauty that make you sit upright. A "trigger warning" might be especially needed for lovers of animals, given the harshness with which they are occasionally treated: There is a scene with a cow on fire that will likely haunt me for a long time. But all the unpleasantness in the film is in service of a story about the persistence of the Russian people and the transcendence of art. Anatoliy Solonitsyn, who plays Rublev, looks a bit like Viggo Mortensen, and recalls for me the tormented masculinity you find in some of Mortensen's performances. Another standout performance is given by Tarkovsky's wife, billed as Irma Raush, as the "holy fool" Durochka, whom Rublev saves from a massacre by the Tatars by killing the assailant -- leading Rublev to atone by giving up his painting and taking a vow of silence. The last section of the film is given over to young Boriska, played by Nikolay Burlyaev, the astonishing Ivan in Tarkovsky's Ivan's Childhood (1962), who takes on the task of casting a church bell despite the suggestion that he will be murdered by the tyrannical Grand Prince if he fails. Although the film is in black-and-white, it concludes with a breathtaking color sequence in which Rublev's paintings are shown in close-up. (To my mind, this final ecstatic survey of Rublev's work is the only section in which Tarkovsky is thwarted by the widescreen process: Rublev's paintings had an aspiring verticality that is at odds with the dimensions of the screen.)