A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, January 4, 2016

Mr. & Mrs. Smith (Alfred Hitchcock, 1941)

If Hitchcock's name were not attached to this movie, would we remember it at all today? Perhaps as one of the last films of Carole Lombard -- it was the last released before her death in January 1942, though the posthumously released To Be or Not to Be (Ernst Lubitsch, 1942) was the last one she completed filming. Or perhaps as one of the lesser examples of the romantic/screwball comedy genre that flourished in the 1930s and '40s. But even hardcore Hitchcockians find it difficult to fit it into the director's canon. Hitchcock had said he wanted to work with Lombard, and when Lombard liked Norman Krasna's story and screenplay, the teaming was put into play. Lombard and Robert Montgomery play Ann and David Smith, who discover that their three-year-old marriage is invalid, owing to a legal technicality. Complications ensue, especially when David doesn't rush into remarriage as quickly as Ann likes. She kicks him out of the apartment, and then his law partner, Jeff Custer (Gene Raymond), makes a play for her affections. Lombard is very much at home in this kind of comedy, but Montgomery is surprisingly good at it too. The weak link is Raymond, who has the kind of role, the "other man" patsy, at which actors like Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937) and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940) and John Howard in The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940) excelled. Raymond plays his part with a pinched, rather prissy manner that hardly sits well with the fact that he's supposed to have been the best fullback at the University of Alabama. In fact, the character seems to have been coded as latently gay: Witness Lombard's reaction when Ann learns that he decorated his own very tasteful apartment. Much of the film skirts around matters forbidden by the Production Code, including whether the now-unmarried Smiths should sleep together, which a director like Lubitsch or Hawks would have treated with more wit and finesse than Hitchcock does. This was only his third film made in Hollywood, and it was his first with a completely American setting; the first two, Rebecca (1940) and Foreign Correspondent (1940), were set in Europe and England. His unfamiliarity with American idiom shows up particularly in his treatment of Jeff and his parents (Philip Merivale and Lucile Watson), proper Southerners who are shocked at the suggestion that Ann has been sleeping with David. But whenever Hitchcock is working with Lombard and Montgomery, especially using Lombard's great gift for uninhibited physical comedy, the movie comes to fitful life.

Sunday, January 3, 2016

La Collectionneuse (Éric Rohmer, 1967)

The French New Wave films launched numerous film acting careers, most notably those of the hyphenated Jeans: Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean-Louis Trintignant, and Jean-Pierre Léaud. One of the longest of them has been that of Patrick Bauchau, the lead actor of Éric Rohmer's La Collectionneuse. Though his name may not be as well-known as the other three, he has worked steadily since his uncredited debut in Rohmer's short film Suzanne's Career (1963), the second of the director's "Six Moral Tales." La Collectionneuse is the fourth of the tales. though it was filmed before the third in the series, My Night at Maud's (1969). It was an impressive feature debut for Bauchau, whose later work includes a turn as a Bond villain in A View to a Kill (John Glen, 1985), and appearances on many American TV series. Bauchau's character, Adrien, is introduced to us in one of three brief prologues. The first shows Haydée (Haydée Politoff) walking along the beach in a bikini. In the second, the artist Daniel (Daniel Pommereulle) discusses one of his pieces, a paint can studded with razor blades, with a writer (Alain Jouffroy). And in the third Adrien and his girlfriend, Carole (Mijanou Bardot), and a friend of hers (Annik Morice), talk about beauty in that elevated French intellectual way familiar to viewers of Rohmer's films. We learn that Adrien is going to stay with Daniel in a house in the south of France while Carole does a modeling job in London. When the two men get to the villa they discover that they're sharing it with the 20-year-old Haydée. The potential of this ménage à trois is obvious, especially after Adrien finds Haydée in bed with a young man -- the first of many. But this being one of Rohmer's morality plays, things do not go quite so obviously. For one thing, Adrien has sworn that he will spend his vacation doing nothing, which includes having sex. He calls Haydée a "collector" because of her sleeping around. But with actors as attractive as the young Bauchau and Politoff the sexual tension persists. The film develops into a satire on the pretensions and artifice of intellectuals, without ever tipping its hand in the direction it's going. (Though there is a priceless Chinese vase -- Adrien is an art dealer -- that is something of a Chekhov's gun.) Much of the film's dialogue was improvised by the three principals. The brilliant cinematography is by Rohmer's frequent collaborator Néstor Almendros.

Saturday, January 2, 2016

My Night at Maud's (Éric Rohmer, 1969)

A moral tale: Once upon a time, a brave and chaste knight saw a fair young lady in church, and wished that she were his. The devil, hearing this, arranged for the knight to be tempted by a beautiful sorceress. But when the knight resisted the carnal temptations of the sorceress, he was rewarded with the love and the hand of the fair young lady. Éric Rohmer's moral tale: Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trintignant), an engineer who has recently moved to Clermont-Ferrand, is an intellectual Catholic, determined at the age of 34 to settle down and get married after several failed love affairs. At mass one day he sees a beautiful young woman (Marie-Christine Barrault), and longs to get to know her. Leaving the church, he sees the woman get on a moped, and he follows her in his car until they are separated by traffic. Jean-Louis runs into an old friend, Vidal (Antoine Vitez), a philosophy professor and a Marxist, who takes him to see his friend, Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorcee. Vidal gets drunk and leaves early, and when it begins to snow heavily, Jean-Louis stays to spend the night with Maud. But they do little more than talk -- about his Catholicism, about the philosophy of Pascal, about his life and hers. She and her husband were unfaithful to each other, and her lover was killed when his car skidded on the ice -- one reason she forbids Jean-Louis to drive in the snow. They literally sleep together: She in the nude, he fully clothed and wrapped in a coverlet she lends him, though both are in the same bed. In the morning he makes a pass at her that she brushes off, and as he looks out the window he sees the young woman he saw at mass, and runs out to introduce himself to her. Her name is Françoise, and she is a student at the university where Vidal teaches. They make a date for later in the day, and afterward he drives her home to her student apartment. Stuck in the snow again, he spends the night, but not in her room: She gives him a key to the apartment of another student who is away. Five years later, they are married and taking their young son to the beach, when they meet Maud on the path. Jean-Louis realizes from Françoise's reaction that she knows Maud -- in fact, Françoise, who has confessed that she had an affair with a married man, may have been the lover of Maud's husband. This is the third of Rohmer's "Six Moral Tales," and perhaps the most successful: It was nominated for Oscars for Rohmer's screenplay and as the best foreign-language film. But a lot of critics and viewers found it insufferably talky in that peculiarly French over-intellectualized way -- a curious objection to a film that features four attractive actors and a strong emphasis on sex. And the talk is far wittier than anything you're likely to hear in a movie today.

Friday, January 1, 2016

Follow the Fleet (Mark Sandrich, 1936)

If Swing Time, as I suggested yesterday, has too little plot, then Follow the Fleet has a bit too much. Dwight Taylor and Allan Scott based their screenplay on a 1922 Broadway play, Shore Leave, by Hubert Osborne, which later became a musical, Hit the Deck. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers of course spark real heat when they're dancing together: As the remark attributed to Katharine Hepburn about the team says, she made him sexy and he made her classy. But I don't find them terribly convincing as a romantic pair when they're not singing and dancing together, and this criticism was not uncommon even in their heyday. Which may be why RKO decided to try to spice things up by creating a parallel romantic team in Follow the Fleet, casting Randolph Scott and Harriet Hilliard as the lovers whose problems echo those of Astaire and Rogers. The trouble is, Scott and Hilliard generate much less chemistry than the lead couple. Scott had always been a sort of second-string Gary Cooper, but without Cooper's charm or acting ability, and Hilliard was best known as a singer with her husband Ozzie Nelson's band when she was signed for this film, her first feature. She sings, rather ineffectively, two of the lesser-known of the seven Irving Berlin songs in the score, "Get Thee Behind Me, Satan" and "But Where Are You?" Follow the Fleet did nothing for her film career. It wasn't until she teamed with Ozzie for the radio series The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet in 1944, and later with their two sons, David and Ricky, for the long-running TV series of the same name, that she became really famous. Fame was in store, however, for several other members of the cast: Betty Grable and a blond Lucille Ball have small parts in the film, and Tony Martin, one of the sailors backing up Astaire, would later star in the film version of Hit the Deck (Roy Rowland, 1955), bringing Hollywood's use of Osborne's play full circle. As for Astaire and Rogers, Follow the Fleet contains two of their most memorable numbers. They do a slapstick dance routine to "I'm Putting All My Eggs in One Basket" that shows Rogers's great gift for physical comedy to full advantage. And then there's "Let's Face the Music and Dance," which is one of their most balletic routines. Astaire does some remarkable footwork and Rogers is clad in an amazing dress that, thanks to weights in the sleeves and hem, swirls around her hypnotically. Once or twice, to be sure, you can see Astaire try to avoid getting swacked by her sleeves. (The designer credited with "gowns" is Bernard Newman.) At the end of this sublime routine, Astaire and Rogers slowly make their way off-stage and then suddenly exit with a breathtakingly unanticipated strut. But why try to describe it?

Thursday, December 31, 2015

Swing Time (George Stevens, 1936)

The plot of a Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers is typically a thread on which the gems (the songs and dances) are strung, and Swing Time is no exception. The screenplay by Howard Lindsay and Allan Scott seems to exist largely to provide opportunities for Astaire and Rogers to open their mouths, the better to sing with, or to find places to dance. For those who care, it's the one in which Astaire plays a gambler named Lucky Garnett, who is late for his wedding to Margaret Watson (Betty Furness), so her father calls it off and says that if Lucky can make $25,000, he can come back to claim her hand. So off he goes to New York, accompanied by his friend Pop Cardetti (Victor Moore), where he falls for Penny Carroll (Rogers), a dance teacher. And so on.... That anything this silly remains watchable 80 years later is the consequence of the unsurpassed artistry of Astaire and Rogers, the dance direction of Hermes Pan, the comic support of Moore, Helen Broderick, and Eric Blore, and six songs by Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields. Rogers does more than her usual share of the singing in this one, taking the lead on both "Pick Yourself Up" and "A Fine Romance," but as usual it's Astaire's peerless phrasing that carries the songs, especially the Oscar-winning "The Way You Look Tonight," which is wittily staged when Rogers enters the room having lathered her hair with shampoo but not yet rinsed it out. The dance highlight is probably "Never Gonna Dance," the climactic number when Lucky and Penny each think they're doomed to marry someone else, but Astaire's solo, "Bojangles of Harlem," a tribute to the great Bill Robinson, is also superb -- as long as you're not offended by the fact that Astaire does it in blackface. (To my mind, the reverence paid to Robinson outweighs the minstrelsy, but only slightly.) Astaire always insisted that dance sequences be done in long takes, which led to 47 reprises of "Never Gonna Dance" during the filming before a take that completely satisfied Astaire was achieved -- at the expense, it is said, of Rogers's feet, which began to bleed. This was the only film role of any consequence for Furness, whose chief claim to fame was that she opened countless refrigerator doors as the TV commercial spokesperson for Westinghouse in the 1950s.

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

Summer With Monika (Ingmar Bergman, 1953)

This early Bergman film, coming before the trifecta of Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), The Seventh Seal (1957), and Wild Strawberries (1957) established his reputation as a director, got its first exposure in the United States in 1955 when an enterprising distributor purchased the rights, cut it by a third, and released it as Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl, with a publicity campaign centered on Harriet Andersson's nude scene. As the original poster at left suggests, the Swedish distributors were not above exploiting Andersson either, but Bergman's adaptation with Per Anders Fogelström of Fogelström's novel, is anything but a naughty sexcapade. It's a film about disaffected youth: Monika and Harry (Lars Ekborg) are in their late teens and trapped in boring jobs. Monika works at a produce store where she is sexually harassed by the male employees, and Harry, a packer and delivery boy in a store that deals in pottery and glassware, is constantly being scolded for being late and lazy. Harry wants to study to be an engineer, but he has to look after his father, who is an invalid. His mother died when he was 8, and he tells Monika that he has always felt alone. Monika is anything but alone: Her father is abusive and her mother barely tends to Monika's noisy young siblings. So when Harry's father goes into a hospital, Monika persuades Harry to run away with her. They steal his father's boat and sail away from Stockholm to the countryside, beautifully filmed by Gunnar Fischer. Their idyll is eventually cut short by their lack of money and Monika's pregnancy. The problem with the film is that a rather puritanical tone eventually seeps in, making Monika the focus of a moral condescension that Bergman would outgrow as his career progressed.

| Promotional posters for the 1955 American release of Summer With Monika |

Mon Oncle Antoine (Claude Jutra, 1971)

The title of Claude Jutra's richly textured film seems to promise a coming-of-age story, which is what, eventually, it delivers. But first the film acquaints us with a Quebec asbestos mining town in the 1940s. The first event we witness is a fight between a miner, Jos Poulin (Lionel Villeneuve), and his boss (Georges Alexander), which is hardly a fight at all because the boss speaks English and Jos doesn't, which easily allows him to ignore what the boss is saying and do what he wants to do: quit the mine and go look for work elsewhere. Our first look at Antoine (Jean Duceppe) is when he's doing his work as the town's undertaker: a comically macabre scene in which the corpse is denuded of the "suit" he was wearing for the viewing, which turns out to be a false front quickly plucked off the naked body and saved for another corpse, and the rosary is untwined from his stiffening fingers. Antoine is the owner, with his wife, Cecile (Olivette Thibault), of the town's general store, which employs his teenage nephew, Benoit (Jacques Gagnon); a teen girl, Carmen (Lyne Champagne), who lives at the store because her skinflint father (Benoit Marcoux), who pockets her earnings, doesn't want to pay for her upkeep; and Fernand (Jutra), who clerks at the store. It's Christmas time, though there's not much sentiment in the film's treatment of the holiday. One of the best scenes in the movie comes when the mine boss rides through the town in a little two-wheeled cart, tossing cheap gifts to the children as the grownups frown at his stinginess and comment that he hasn't given out any raises or bonuses. Benoit and a friend throw snowballs at the horse, causing the boss to beat a hasty retreat. One of the most celebrated of Canadian films, Mon Oncle Antoine benefits from Jutra's adaptation with Clément Perron of Perron's story, and from Michel Brault's cinematography, but most of all from the great credibility of its cast.

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

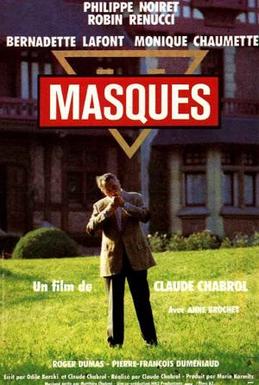

Masques (Claude Chabrol, 1987)

Masques shares the style (and the one-word title) of those 1960s romantic thrillers like Charade (Stanley Donen, 1963), Arabesque (Stanley Donen, 1966), and Kaleidoscope (Jack Smight, 1966) that inevitably got called "Hitchcockian." So it's not surprising that Chabrol, who recognized Hitchcock's genius when Hollywood still thought of him as just a popular entertainer, should cast an hommage to the director in their manner. Roland Wolf (Robin Renucci) is writing a biography of Christian Legagneur (Philippe Noiret), who hosts a cheesy TV talent/game show featuring senior citizens, so he comes to spend a week at Legagneur's estate near Paris. There he's introduced to a houseful of eccentrics: Legagneur's mute chauffeur/cook, Max (Pierre-François Dumeniaud); his secretary, Colette (Monique Chaumette); and a couple, Manu (Roger Dumas), a wine connoisseur who is helping stock Legagneur's cellar, and his wife (or perhaps mistress), who is a masseuse and reads tarot cards (Bernadette Lafont). (Lafont gets third billing after Noiret and Renucci, though hers is decided a secondary role, perhaps because she appeared in Chabrol's first film, Le Beau Serge, in 1958, and worked with him again several times during their long careers.) But most intriguing of all to Wolf is Legagneur's pretty young goddaughter, Catherine (Anne Brochet), who Wolf is told is recovering from a serious illness and is quite fragile. It's clear to the audience from Catherine's erratic behavior that she's drugged -- whether as part of her therapy or not is the question raised in Wolf's mind. For no one in this household is exactly what they seem, least of all Wolf, who, when he's alone in his room, removes a gun from his shaving kit and hides it on a shelf. On the shelf he finds a lipstick and with it, murmuring "Madeleine," he writes a large "M" on a mirror, then rubs it out. Madeleine, we will learn, is Wolf's sister, who is said to have quarreled with Catherine and then left on a trip to the Seychelles, which Wolf seriously doubts. Madeleine is also, of course, the name of the character played by Kim Novak in Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958), one of several "Easter eggs" for Hitchcockians left by Chabrol in the film. Legagneur's TV show, for another example, uses as theme music Gounod's "Funeral March for a Marionette," which was the theme music for Hitchcock's own TV show. Masques failed to find an American distributor when it was first released, but is now available on video. It's definitely minor Chabrol, but Noiret is terrific as the affably sinister Legagneur.

Monday, December 28, 2015

La Cérémonie (Claude Chabrol, 1995)

|

| Valentin Merlet, Jacqueline Bisset, Virginie Ledoyen, and Jean-Pierre Cassel in La Cérémonie |

Sophie: Sandrine Bonnaire

Georges Lelièvre: Jean-Pierre Cassel

Catherine Lelièvre: Jacqueline Bisset

Melinda: Virginie Ledoyen

Gilles: Valentine Merlet

Jérémie: Julien Rochefort

Mme. Lantier: Dominique Frot

Priest: Jean-François Perrier

Director: Claude Chabrol

Screenplay: Claude Chabrol, Caroline Eliacheff

Based on a novel by Ruth Rendell

Cinematography: Bernard Zitzerman

Production design: Daniel Mercier

Film editing: Monique Fardoulis

Music: Matthieu Chabrol

Claude Chabrol's La Cérémonie begins with a long tracking shot through the window of a café, picking up Sophie as she walks toward her appointment with Catherine Lelièvre. Catherine is as chic as Sophie, boyishly dressed with her hair cut in too-short bangs, is drab. The Lelièvres need a housekeeper, Catherine tells her, and Sophie presents the letter of reference from her most recent employer. The interview is slightly awkward, partly because Sophie is oddly oblique in her answers. But Catherine has a large house in a remote location and she needs a housekeeper right away. When Catherine drives Sophie to the house, a young woman named Jeanne appears and hitches a ride to the village near the Lelièvres house; Jeanne, who is as brashly forward as Sophie is reserved, works in the village post office. At the house, Sophie meets Catherine's husband, Georges, a rather blustery businessman, and her son from a previous marriage, the teenage Gilles, and stepdaughter, a university student named Melinda. Sophie proves to be an excellent cook and a reliable maid-of-all-work, but we soon discover that she has a secret or two. One is that she's illiterate, the result of a profound dyslexia. She doesn't drive, being unable to pass a driving test, and pretends that she needs glasses. When Georges insists on taking her to an optometrist, she ducks out of the appointment and buys a cheap pair of drugstore glasses -- though even then she is unable to give the sales clerk the exact change. Waiting for Georges, she meets Jeanne again, and the two women strike up a friendship. Jeanne, it turns out, knows another secret of Sophie's, which is that she was accused of setting fire to her house, killing her disabled father. Jeanne herself was accused of abusing her daughter, born out of wedlock, and causing her death, but both women were acquitted for lack of evidence. And so the stage is set for a story of folie à deux that Chabrol and Caroline Eliacheff adapted from a novel, A Judgment in Stone, by Ruth Rendell. Bonnaire and Huppert are extraordinary in their contrasting styles: Bonnaire passive, almost autistic in manner, Huppert bold and outgoing. The climax, in which a frenzied Jeanne releases Sophie's pent-up hostility, is shattering.

Story of Women (Claude Chabrol, 1988)

"Women's business," according to the subtitle, is what Marie Latour (Isabelle Huppert) tells her husband (François Cluzet) is going on behind closed doors in their apartment. The business is abortion, which Marie provides for prostitutes and other women who are finding childbirth to be a burden during the German occupation of France. But "Women's Business" might also be an apt translation of the original title of Chabrol's film, Une Affaire de Femmes. Based on the true story of Marie-Louise Giraud, who went to the guillotine in 1943 for the abortions she had induced, Story of Women is a deeply feminist film, though never a preachy one. Huppert, as usual, gives an extraordinary performance, emphasizing not only her character's determination to do what she thinks is right for the women she knows, but also her profoundly fatal naïveté about the politics of the era in which she is living. "Women's business" is to survive the ignorance and brutality of men, by any means necessary, but it betrays Marie into some choices that a woman with more knowledge of the way the world works might avoid. She loses sight of the fact that she became an abortionist to survive the deprivation that threatens her life and that of her children, and becomes fixated on their greatly improved standard of living and the possibility that she might earn enough to fulfill her dream of becoming a professional singer. (A distant dream, as her performance of a song in an audition for a music teacher suggests.) In the end, she goes to a guillotine that is not the toweringly glamorous instrument of death we've grown accustomed to from films about the French Revolution, but a grim and shabby little affair cobbled together from plywood and sheet metal -- a fitting image for the shabbiness of the Vichy régime and its treatment of those it saw as a threat.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)