A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, December 7, 2016

Le Samouraï (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967)

Was anyone, even Jean-Paul Belmondo, ever as cool as Alain Delon is in Le Samouraï? It's not just that he's beautiful, for beauty often works against men in the movies: They get classified as "pretty boys" and stuck in roles in which they're shown up by the more rough-hewn types. It's not just that he shows no emotion, or hardly ever; that could easily be mistaken for "limited acting range." It's not just that he wears clothes -- trenchcoat and carefully placed hat -- elegantly. It's not just that he's playing the movies' most evocative loner, the hit man, whose monomaniacal pursuit of his mission invokes a bit of paranoia in us all. Or that, in its 1960s context, the film echoes the rage against order that stirred youth revolt around the world. Or that he evokes the detachment of existentialist heroes like Meursault in Camus' The Stranger. It's all of these things, of course, but mostly it's that Jean-Pierre Melville, in script (co-written with Georges Pellegrin) and direction, is able to create the perfect atmosphere -- part detective story, part American film noir hommage, part romanticism -- around the character of Jef Costello -- even the name, with its missing "f" and its evocation of the Italian-American mobster Frank Costello, has a certain weird glamour. (The Italian release was called Frank Costello faccia d'angelo, i.e., "Frank Costello Angel Face.") Delon is the perfect choice for the role, emphasizing the absurdity of the premise that someone so striking in appearance could go about his bloody work unnoticed. The absurdity is of course intentional on Melville's part, making mock of the glamorizing of violence. Similarly, the title mocks the glamorizing of violence in samurai films -- not so much those of Kurosawa and Kobayashi as the less-prestigious entries in the genre. The mockery is, however, not malicious but affectionate, and only comic in retrospect. I don't know many other films who unfold themselves so remarkably upon reflection.

Sunday, December 4, 2016

Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938)

Although it's often called the greatest of all screwball comedies, to my mind Bringing Up Baby transcends that label: It's the finest example I know of a nonsense comedy. Screwball comedies like My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava, 1936) and Nothing Sacred (William A. Wellman, 1937) usually have one foot in the real world -- the Depression and its Hoovervilles in the case of the former, exploitation journalism in the latter. Bringing Up Baby exists only in a universe where an impossible thing like an "intercostal clavicle"* could exist. Its world is a place where nobody listens to anyone else and everyone seems to be marching to their own drummer. It's what puts Bringing Up Baby in the sublime company of Lewis Carroll's works or James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. Fortunately it's more accessible than the latter and at least as much fun as the former. Nonsense is harder to bring off on film than in literature. Cinema by nature is a documentary medium -- one that's assumed to be recording reality -- and has less flexibility than words do. It's also a collaborative medium, which means that everyone involved in writing, directing, and acting in it has to be on the same wave length, or the whole thing will collapse like a soufflé with too many cooks. That's why Bringing Up Baby is almost sui generis: The only other movies that approach the sublimity of its nonsense are some of the ones with the Marx Brothers or W.C. Fields. Even Howard Hawks once admitted that he thought he had gone too far in crafting a comedy with "no normal people in it." Nevertheless, the soufflé continues to rise, thanks in very large part to Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, whose four movies together -- the other three were directed by George Cukor: Sylvia Scarlett (1935), Holiday (1938), and The Philadelphia Story (1940) -- seem to me to demonstrate a more potent teaming than the more iconic one of Hepburn with Spencer Tracy. And then there's the sine qua non of the screwball comedy, a supporting cast of character players like Charles Ruggles, Walter Catlett, Barry Fitzgerald, May Robson, and Fritz Feld. The screenplay was put together by Dudley Nichols and Hagar Wilde, from a magazine story by Wilde that Hawks bought and then with their help -- and doubtless much ad-libbing from the cast -- revised out of all recognition. I only hope that whoever came up with the phrase "intercostal clavicle," which Grant delivers with such delight in its rhythms, received a bonus.

*In case you've never thought to look it up, "intercostal" means "between the ribs" and usually refers to the muscles and spaces in the ribcage. The clavicle, or collarbone, sits atop the ribs and therefore can't be between them.

Saturday, December 3, 2016

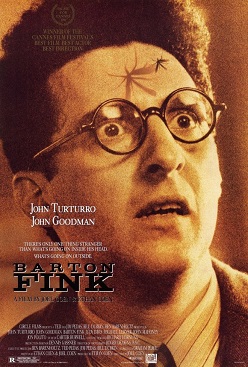

Barton Fink (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1991)

The Coen brothers are nothing if not audacious, and attempting something so outrageous and anomalous as Barton Fink at the beginning of their careers -- it was their fourth feature, after Blood Simple (1984), Raising Arizona (1987), and Miller's Crossing (1990) -- shows a certain amount of courage. It's a curious melange of satire, horror movie, comedy, thriller, fantasy, and fable that had many critics singing its praises. It was their first film to receive notice from the Motion Picture Academy, earning three Oscar nominations: supporting actor Michael Lerner, art directors Dennis Gassner and Nancy Haigh, and costume designer Richard Hornung. And it was the unanimous choice for the Palme d'Or at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival; Joel Coen also won as best director and John Turturro as best actor. Evidently it took everyone by surprise. But I have to admit that although it's a provocative and unsettling movie, I don't much care for it. There's not enough of any one element in the melange to suggest to me that it's anything other than the work of a couple of extraordinarily talented writer-directors riffing on whatever comes to their minds. Barton (Turturro) is a playwright whose hit on Broadway in 1941 gets him a bid to come work in Hollywood. There, studio head Jack Lipnick (Lerner) assigns him to write a wrestling picture for Wallace Beery. Stymied in his attempt to come up with a screenplay, Barton decides to pick the brain of a famous novelist who has also come to work in Hollywood, W.P. Mayhew (John Mahoney). The playwright, the studio head, and the novelist are all caricatures of Clifford Odets, Louis B. Mayer, and William Faulkner, respectively. To my mind, this real-world reference point throws the film off center. Each caricature is well-done: What we see of Barton's play is a deft parody of the Odets-style leftist "little people" dramas like Waiting for Lefty and Awake and Sing! that Odets was known for. Lipnick is a rich, sentimental vulgarian with a mean streak, who like Mayer was born in Minsk. And Mayhew not only goes by the name "Bill," as Faulkner did among his friends and family, he also has a wife back home named Estelle, just as Faulkner did. Moreover, he is an alcoholic who is looked after in Hollywood by his mistress, Audrey Taylor (Judy Davis), who is clearly based on Faulkner's Hollywood mistress, Meta Carpenter. But then we have the turns into horror-fantasy when Barton tries to hole up in a Los Angeles hotel and makes friends with his next-door neighbor, an insurance salesman named Charlie Meadows (John Goodman). Good-time Charlie is later revealed to be a serial killer named Karl Mundt -- another of the Coens' in-jokes, I think: The real-life Karl Mundt was a right-wing dunce who represented South Dakota (neighbor state to the Coens' Minnesota) in Washington from 1939 to 1973. Clearly, Barton Fink is not without a certain baroque fascination to it. It's the kind of film you can spend hours analyzing and annotating. And this makes it, for me, little more than a fabulous mess.

Zootopia (Byron Howard and Rich Moore, 2016)

More evidence that this is a golden age for animation, especially with the perfecting of computer-animation techniques. But Zootopia's success lies as much in its story and its voice actors as in its technology. Actually, the success of the story is a bit of a surprise, considering that it was created by a committee and went through many alterations before settling on the central thread of a young rabbit, Judy Hopps (voice of Gennifer Goodwin), who wants to be a cop, and eventually teams up with a con-man fox, Nick Wilde (voice of Jason Bateman), to solve the mysterious disappearances of several residents of Zootopia, a place where predators and prey have learned to live together amicably. It seems that the disappeared were all predators who "turned feral" before they vanished. No fewer than seven credited writers -- and doubtless many more uncredited -- worked on the story before it was turned into a screenplay by Phil Johnston and Jared Bush (the latter also receives a credit as "co-director," whatever that means). Goodwin and Bateman are full of charm in their line delivery, and Idris Elba, as Judy's blustering and bellowing police chief, brings great energy to his role. Like so many recent computer-animated features, it is sometimes over-crowded with gags taking place on the periphery that it's possible to get a little distracted by them: a sure way of enticing people to watch the movie more than once.

Friday, December 2, 2016

The Bank Dick (Edward F. Cline, 1940)

This is what I watched on election night once it became apparent that the votes might take the depressing direction they eventually did. Better a lovable con man like W.C. Fields than a real-life flamboyant fraud, thought I. Fields is Egbert Sousé (the accent is aigu, not grave, as he insists), ne'er-do-well paterfamilias of a dysfunctional household, who escapes from his nagging wife (Cora Witherspoon) and mother-in-law (Jessie Ralph) and his horrid daughters Myrtle (Una Merkel) and Elsie Mae (Evelyn Del Rio) to the corner saloon as well as a brief stint as a movie director that somehow leads to his employment as a detective in the local bank. (Honestly, never try to summarize the plot of one of Fields's movies.) It's all inspired, slightly surreal nonsense, adorned by characters with names like Og Oggilby (Grady Sutton), J. Pinkerton Snoopington (Franklin Pangborn), and A. Pismo Clam (Jack Norton). All I can say is that it made me laugh when I felt like crying.

Nora (Pat Murphy, 2000)

A rather muddled and unsatisfactory account of the domestic life of James Joyce (Ewan McGregor) and Nora Barnacle (Susan Lynch), adapted by Murphy and Gerard Stembridge from Brenda Maddox's excellent biography, Nora. There's not enough narrative drive in this account of their lives up to the publication of Dubliners. Mostly the film deals with the squabblings of the pair, who while mismatched intellectually seemed to have a kind of irresistible attraction to each other. The movie seems aimed at viewers with a ready knowledge of Joyce's life and work, especially the cultural and familial pressures that drove him into a life of exile from Ireland, but anyone who already possesses that knowledge is likely to be left frustrated by what appears on screen. Lynch is excellent in the title role, but McGregor never penetrates to the essence of the brilliant, self-tormenting genius of Joyce.

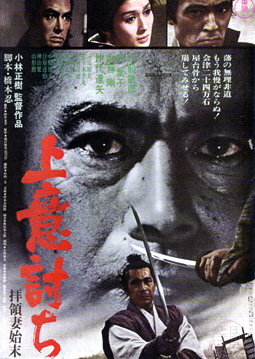

Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967)

Like his Harakiri (1962), Kobayashi's Samurai Rebellion has a theatrical, almost Shakespearean quality and is sharply critical of the samurai code of honor. Toshiro Mifune plays Isaburo, a samurai whose son Yogoro (Go Kato) is ordered to marry the concubine Ichi (Yoko Tsukasa) of the daimyo of the clan he serves. Yogoro is reluctant, partly because Ichi has a son by the daimyo, but eventually they fall in love. Unfortunately, the daimyo's older son dies, making Ichi's child the heir, and she is ordered to return to his household. The ensuing rebellion against the daimyo's order proves calamitous for all concerned. The beautifully committed performances by all concerned heighten the story's tragic drive. The film's English title was apparently designed to convince Western audiences that they were going to see a conventional samurai film, whereas it's really a story about the heroism of Ichi, giving a distinctly feminist spin to the genre.

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

Nothing Sacred (William A. Wellman, 1937)

It's a bit startling to see a classic screwball comedy like Nothing Sacred in color. We're used to movies from the 1930s in the crisp elegance of black and white, so if you came across this movie without knowing anything about it, you might think it was one of those films that Ted Turner tried to "colorize." Part of the problem is that the tones in early Technicolor films are so muted: Some have faded with age, but getting the true sharp color contrasts that we're used to was more difficult in these early films, especially since Technicolor had very conservative ideas about what could be done with the process, and its "consultants," like the oft-credited Natalie Kalmus, the wife of the company's founder, were there to peer over the cinematographer's shoulder at all times. In addition, one of the problems with the color on Nothing Sacred is that a lapse of copyright on the film allowed many inferior prints to circulate before it could be restored to its original version. To my way of thinking, color adds little to this particular film, except in the glimpses of New York City in 1937. Carole Lombard plays Hazel Flagg, who, through a misdiagnosis by her small-town Vermont physician, Dr. Downer (Charles Winninger), is thought to be dying of radium poisoning. A New York reporter, Wally Cook, reads a short item about Hazel in the newspaper and persuades his editor, Oliver Stone (Walter Connolly), that it has the makings of a circulation-building sob story. Although Hazel and her doctor have subsequently learned that she's perfectly healthy, they agree to go along with the scheme to celebrate her as a dying heroine in the big city. And so it goes, in a frequently deft skewering of high-pressure journalism -- the very thing you might expect from the screenwriter, Ben Hecht, a former newspaperman who did a similar skewering in his play The Front Page. After Hecht had a falling-out with the film's producer, David O. Selznick, the screenplay was worked over by a number of uncredited wits, including Dorothy Parker, Moss Hart, George S. Kaufman, and Budd Schulberg. The film could have used a somewhat lighter hand at directing: William A. Wellman is best known as a tough guy -- his nickname was "Wild Bill" -- with credits like Wings (1927), The Public Enemy (1931), The Story of G.I. Joe (1945), and Battleground (1949), but he does get to stage a very funny fight scene between Lombard and March.

Monday, November 28, 2016

The Sea of Trees (Gus Van Sant, 2015)

For a movie that attempts a "feel-good" ending, The Sea of Trees sure does spend a lot of time making you feel bad, from the moment its grim-faced protagonist, Arthur Brennan (Matthew McConaughey), arrives in Japan. He plans to kill himself in the "Suicide Forest" near Mount Fuji. But then he tries to help Takumi Nakamura (Ken Watanabe), a man he meets there, find his way out of the forest, and encounters all manner of hardships and injuries. There are also flashbacks to Arthur's troubled marriage and the death of his wife, Joan (Naomi Watts). We are plunged into one misery after another before a twist into fantasy convinces Arthur not only that life is worth living but also that love persists after death. Yet the misery dominates the tone of the film, despite three excellent actors and a well-regarded director, Gus Van Sant. Some of the blame must fall on the screenwriter, Chris Sparling, but mostly it seems to be a failure to leaven the material with anything that gives us a sense that the promise of its ending has been earned. Imagine Ghost (Jerry Zucker, 1990) without Whoopi Goldberg and instead two hours of moping around by Demi Moore recalling life with Patrick Swayze, and you'll have a sense of the overall effect of The Sea of Trees. One major problem, I think, is in the miscasting of McConaughey as the lead. He's a very good film actor, as his Oscar-winning performance in Dallas Buyers Club (Jean-Marc Vallée, 2013), his scene-stealing bit in The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013), and his work on the first season of the series True Detective (2014) amply demonstrates. But he is, I think, a character lead, terrific in roles full of wit and sass and energy, whereas what's called for in films like The Sea of Trees is a conventional romantic leading man. As hard as he works to make it plausible, his character in this film never rings true. But then not much else in the film does, either.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)