Movie: La Piscine (Jacques Deray, 1989) (Criterion Channel).

Book: William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, ed. Kenneth Palmer.

TV: Buddy vs. Duff, Holiday: Winter Wonderland (Food Network); The Rachel Maddow Show (MSNBC); Maid: Bear Hunt.

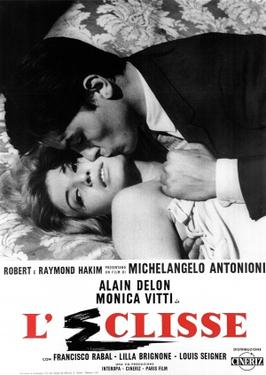

Jean-Paul (Alain Delon) and Marianne (Romy Schneider) are types familiar to viewers of French films: lovers with too much time on their hands and not enough to occupy them. He's a failed novelist who has tried to get his life back on track by giving up alcohol and going to work for an advertising agency, and the two of them have been together for two years -- or two and a half, as he insists, perhaps a little touchily, when they're asked. Now they're on vacation in a villa on the Riviera, where they don't seem to do much but lounge around the titular swimming pool, make love, and occasionally quarrel a bit. But then they're visited by Harry (Maurice Ronet) and his 18-year-old daughter, Pénélope (Jane Birkin). Harry was a kind of mentor to the younger Jean-Paul and he was also Marianne's lover for a while. in this leisurely sun-drenched paradise they don't have much to do other than pick at one another. Pénélope is the image of boredom as she slinks around the pool, never going in. When she picks up a book, it's a mystery novel she's read before. (Jean-Paul tells her who did it. She replies, "I know.") The sexual tension relieves itself with Harry and Marianne reigniting their relationship and Jean-Paul hooking up with Pénélope, a state of things that eventuates in murder. But the murder is backgrounded to the exploration of the principal characters in a kind of morality tale about the dangers of dolce far niente. A less skillful director than Jacques Deray or a screenwriter other than Jean-Claude Carrière might have begun with the murder and based the plot on discovering the killer, but La Piscine is more about why this particular killing took place -- what led Jean-Paul to drown Harry in the pool. The bit of detective work that's shown almost outs him, but the complexity of motivation is up for the viewer to piece together. The film ends with Jean-Paul and Marianne ambiguously together.

It has to be said that a lot of the film's effect has to do with its stars and their own pasts: Delon and Schneider had been lovers, the delight of the French gossip press, some time before they reunited for this film. Birkin had come to prominence as a model in the Carnaby Street era of Swinging London. And Ronet was known for his performances as haunted men in Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1958) and The Fire Within (1963), not to mention the previous film in which he was offed by Delon, Purple Noon (René Clément).

|

| Alain Delon and Romy Schneider in La Piscine (Jacques Deray, 1969) |

.jpg)