Montage, the assembling of discrete segments of film for dramatic effect, is what makes movies an art form distinct from just filmed theater. Which is why it's odd that so many filmmakers have been tempted to experiment with abandoning montage and simply filming the action and dialogue in continuity. Long takes and tracking shots do have their place in a movie: Think of the suspense built in the opening scene in Orson Welles's Touch of Evil (1958), an extended tracking shot that follows a car with a bomb in it for almost three and a half minutes until the bomb explodes. Or the way Michael Haneke introduces his principal characters with a nine-minute traveling shot in Code Unknown (2000). Or, to consider the ultimate extreme of anti-montage filmmaking, the scenes in Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975), in which the camera not only doesn't move for minutes on end, but characters also walk out of frame, leaving the viewer to contemplate only the banality of the rooms in which the title character lives her daily life. But these shots are only part of the films in question: Eventually, Welles and Haneke and even Akerman are forced to cut from one scene to another to tell a story. Alfred Hitchcock was intrigued with the possibility of making an entire movie without cuts. He couldn't bring it off because of technological limitations: Film magazines of the day held only ten minutes' worth of footage, and movie projectors could show only 20 minutes at a time before reels needed to be changed. In Rope, Hitchcock often works around these limitations by artificial blackouts in which a character's back fills the frame to mask the cut, but he sometimes makes an unmasked quick cut to a character entering the room -- a kind of blink-and-you-miss-it cut.* But for most of the film, we are watching the action in real time, as we would on a stage. Rope began as a play, of course, in 1929, when Patrick Hamilton's thinly disguised version of the 1924 Leopold and Loeb murder case was staged in London. Hitchcock, who had almost certainly seen it on stage, asked Hume Cronyn to adapt it for the screen and then brought in Arthur Laurents to write the screenplay. To accomplish his idea of filming it as a continuous action, he worked with two cinematographers, William V. Skall and Joseph A. Valentine, and a crew of camera operators whose names are listed -- uniquely for the time -- in the opening credits, developing a kind of choreography through the rooms, designed by Perry Ferguson, that appear on the screen. The film opens with the murder of David Kentley (Dick Hogan) by Brandon (John Dall) and Philip (Farley Granger), who then hide his body in a large antique chest and proceed to hold a dinner party in the same room, serving dinner from the lid of the chest, which they cover with a cloth and on which they place two candelabra. The dinner guests are David's father (Cedric Hardwicke), his aunt (Constance Collier), his fiancée, Janet (Joan Chandler), his old friend and rival for Janet's hand (Douglas Dick), and the former headmaster of their prep school, Rupert Cadell (James Stewart). Everyone spends a lot of time wondering why David hasn't shown up for the party, too, while Brandon carries on some intellectual jousting with Rupert and the others about whether murder is really a crime if a superior person kills an inferior one, and Philip, jittery from the beginning, drinks heavily and starts to fall to pieces. Murder will out, eventually, but not after much talk and everyone except Rupert, who returns to find a cigarette case he pretends to have lost, has gone home. There is one beautifully Hitchcockian scene in the film, in which the chest is positioned in the foreground, and while the talk about murder goes on off-camera, we watch the housekeeper (Edith Evanson) clear away the serving dishes, remove the cloth and candelabra, and almost put back the books that had been stored in the chest. It's a rare moment of genuine suspense in a film whose archness of dialogue and sometimes distractingly busy camerawork saps a lot of the necessary tension, especially since we know whodunit and assume that they'll get caught somehow. Some questionable casting also undermines the film: Stewart does what he can as always, but is never quite convincing as a Nietzschean intellectual, and Granger's disintegrating Philip is more a collection of gestures than a characterization. The gay subtext of the film emerges strongly despite the Production Code, but today portrayals of gay men as thrill-killers only adds something of a sour note, even though Dall and Granger were both gay, and Granger was for a time Laurents's lover.

*Technology has since made something like what Hitchcock was aiming for in Rope possible. Alexander Sokurov's 2002 Russian Ark consists of a single 96-minute tracking shot through the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg as a well-rehearsed crowd of actors, dancers, and extras re-create 300 years of Russian history. Projectors today are also capable of handling continuous action without the necessity of reel-changes, making possible Alejandro Iñárruitu's Oscar-winning Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014), with its appearance of unedited continuity, though Iñárritu and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki resorted to masked cuts very much like Hitchcock's.

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, February 18, 2017

Friday, February 17, 2017

Downhill (Alfred Hitchcock, 1927)

I'd like to be able to make some cogent comparisons of this silent film directed by Alfred Hitchcock to the sound films I've watched recently, but aside from reinforcing the often-made point that his work in the silent era taught him the valuable lesson that showing is better than telling, there's not much of a link between Downhill and Vertigo (1958), Rear Window (1954), or Psycho (1960). Downhill (retitled When Boys Leave Home for its American release) is a standard melodrama about the calamity brought upon a schoolboy by a shopgirl's accusation and the promise he made that prevents him from revealing the truth. Roddy Berwick (Ivor Novello) is a rich young man whose roommate, Tim Wakeley (Robin Irvine), a student attending the school on a scholarship, gets a shopgirl, Mabel (Annette Benson), in what they used to call "trouble." (Or so she supposedly says: No intertitles explicitly reveal the nature of her accusation.) But Mabel pins the blame on Roddy because his family has money. Roddy nobly takes the rap, promising not to reveal the truth because Tim would lose his scholarship. The sequence that sets up the premise for the rest of the film is slow, overlong, and made a bit murkier than it should be by Hitchcock's refusal to use intertitles. But once Roddy leaves school in disgrace and is kicked out by his father (Norman McKinnel), the film picks up the pace. (It's also something of a break for Novello, who was in his mid-30s when the film was made, a bit old to convincingly play a schoolboy.) The first really Hitchcockian touch in the film comes when we find the disgraced Roddy as a waiter, serving a couple at a table in a cafe. The woman leaves her cigarette case behind, and Roddy slips it into his pocket. Has he fallen so far that he now resorts to larceny? No, the camera angle shifts, and we suddenly find that we are onstage. Roddy is a member of the chorus of a musical comedy, and he has taken the case so he can return it to the star of the show, Julia Fotheringale (Isabel Jeans), with whom he is smitten. It's a witty bit of staging that shows the hand of the master. Suffice it to say, things do not go well for Roddy: He inherits a small fortune from his godmother, which makes him an easy mark for the golddigging Julia, whom he marries and who bankrupts him. He becomes a gigolo in a Montmartre dance hall, and declines further until we find him, dissipated and ill, in a Marseilles rooming house. His fortunes take a turn when some sailors, scheduled for trip to England, decide that his family must have money and take him along to collect a reward for returning him. So Roddy makes his way home and is welcomed by his father, who, having learned the truth, has been searching for him all this time. This rather soppy stuff was devised by Novello himself for a play he co-wrote with Constance Collier under the pseudonym David L'Estrange. It was adapted into a scenario by Eliot Stannard, a frequent collaborator with Hitchcock in the silent era. Though the film is on the whole a dud, there are a few moments of brilliance, particularly a stunning scene when a patron in the dance hall suffers some kind of attack and the waiters draw back the curtains to let in fresh air. The morning light floods the hall, revealing the shabbiness of the locale and its aging, over-made-up customers. The scenes in the squalid Marseilles house are also beautifully illuminated by cinematographer Claude L. McDonnell. And those who know of Hitchcock's fear of policemen will relish the first sight Roddy has when he reaches England at the end: a stern-looking bobby patrolling the harbor.

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

I think the most Hitchcockian moment in Psycho is the scene in which Norman disposes of the evidence by sinking Marion Crane's Ford in the swamp with her body and the slightly less than $40,000 she stole in its trunk. We watch as the car slowly settles into the murk with a comically disgusting blurping sound. And then it stops, and we watch Norman's face as he anxiously bites his lip. But just as he is starting out to see if he can help sink it farther, the blurping noise returns and the car sinks to the depths. Who doesn't feel Norman's anxiety and relief in that scene, even though he's a psychotic murderer? This trick of alienating viewers from their own moral values is essential to the greatness of Alfred Hitchcock. On the other hand, I used to think that the least Hitchcockian moment in the film was the psychiatrist's long-winded explanation of Norman's dual-personality disorder, which tells us nothing that we don't already know. But now I think it's a bit of masterstroke. Simon Oakland's performance as the psychiatrist is so florid and self-satisfied that it reveals the character as a pompous showboater, which only heightens the cool, ironic smugness of Norman/Mother in the film's chilling final moment. He/she wouldn't hurt a fly, indeed. What is there to say about Psycho otherwise? That Anthony Perkins is nothing short of brilliant as Norman? Of course. That Janet Leigh's Marion is so well-crafted that we wish she'd been given roles this good throughout her career as a mostly decorative actress? Yes. That Bernard Herrmann deserved all the Oscars he never got for his work on Hitchcock's films? His score for Psycho, for which Hitchcock rewarded Herrmann with a screen credit just before his own as director, didn't even get a nomination -- but then, neither did his scores for The Trouble With Harry (1955), The Wrong Man (1956), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), and Marnie (1964). For that matter, Psycho didn't receive a nomination for George Tomasini's film editing, despite the shower scene, a literal textbook example of the art. (That the scene had been storyboarded -- perhaps with the aid of graphic designer Saul Bass, who later even claimed that he had directed it -- doesn't deny the fact that someone, namely Tomasini, had to lay hands on the actual film.) Yet Psycho remains one of the inexhaustible movies, those in which you see something new and different at each viewing, even if it's only to add to your stock of trivia. This time, for example, I was struck by the fact that one of the cops guarding Norman at the end looked vaguely familiar. I checked, and he was played by Ted Knight -- The Mary Tyler Moore Show's Ted Baxter. How can you not love a film that provides revelations like that?

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

Certified Copy (Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

In the middle of Certified Copy, just after the film has taken a startling narrative turn, we see a man apparently angrily berating his wife. It looks like a correlative to the tensions that seem to be building between the film's protagonists, the unnamed woman who is labeled Elle in the screenplay (Juliette Binoche) and the writer James Miller (William Shimell). But then the man turns slightly and we see that his tirade is actually directed at someone he's talking to on his mobile phone. When our protagonists talk to the man and the woman, they turn out to be an affectionate couple. (The man is played by the celebrated screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, the woman by Agate Natanson.) Nothing is what it seems in Certified Copy, of course, but if you've watched any of Abbas Kiarostami's films, you're probably ready to be tricked or tantalized. That "startling narrative turn" I mentioned above completely changes our assessment of Elle and James, who begin the film as apparent strangers to each other, and then at mid-film start apparently pretending to be a married couple who, by the end of the film, are supposedly revisiting the scene of their honeymoon 15 years earlier. The pivotal scene in Certified Copy takes place in a cafe in Lusignano, where James steps outside to take a phone call. The owner's wife (Gianna Giachetti) assumes that Elle and James are a married couple and asks why they speak English with each other, since she's French. Elle doesn't set the woman straight about their relationship, and there is a sudden break in which the woman's back is turned to the camera and she whispers something we don't hear to Elle. Then, when James returns, they pretend to be (or become?) the married couple, and he speaks to her in French. There are a few tantalizing hints that they may in fact be a long-married couple reuniting after a separation, having pretended at the start of the film to be strangers to each other. There is an equally strong suggestion that they may be strangers who have discovered a mutual love of role-playing. Or there is a third possibility, that the film depict two actualities: i.e., that its first half depicts one couple and its second half the other. If so, Certified Copy resembles Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch, 2001), with its unexplained mid-film narrative disjunction, more than it does the other films about enigmatic relationships or disintegrating marriages to which it has frequently been compared: Journey to Italy (Roberto Rossellini, 1953), L'Avventura (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960), and Last Year in Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961). The title of the film refers to the book James has written about art, in which he argues that the distinction between an "original" work of art and a copy of it is irrelevant. Consequently, Kiarostami, who wrote the screenplay with Caroline Eliacheff, plays with duplicates and mirrors throughout the film, with the help of cinematographer Luca Bigazzi. There is, for example, a wonderfully tricky shot of James standing by a motorcycle with his image reflected in a mirror inside a doorway while Elle's is reflected in the motorcycle's distorting wide-angle mirror. In short, Certified Copy is a dazzling tease of a film that gets inside your head. Whether it's more than that probably depends on how willing you are to unpack its intricacies.

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954)

An almost perfect movie. Rear Window has a solid framework provided by John Michael Hayes's screenplay, which has wit, sex, and suspense in all the right places and proportions. The action takes place in one of the greatest of all movie sets, designed by J. McMillan Johnson and Hal Pereira and filmed by Alfred Hitchcock's 12-time collaborator, Robert Burks. The jazzy score by Franz Waxman provides the right atmosphere, that of Greenwich Village in the 1950s, along with pop songs like "Mona Lisa" and "That's Amore" that come from other apartments and give a slyly ironic counterpoint to what L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart) sees going on in them. It has Stewart doing what he does best: not so much acting as reacting, letting us see on his face what he's thinking and feeling as as he witnesses the goings-on across the courtyard or the advances being made on him by Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly) in his own apartment. It's also Kelly's sexiest performance, the one that makes us realize why she was Hitchcock's favorite cool blond. They get peerless support from Thelma Ritter as Jefferies's sardonic nurse, Wendell Corey as the skeptical police detective, and Raymond Burr as the hulking Lars Thorwald, not to mention the various performers whose lives we witness across the courtyard. It's a movie that shows what Hitchcock learned from his apprenticeship in the era of silent film: the ability to show rather than tell. In essence, what Jeffries is watching from his rear window is a set of silent movies. That Hitchcock is a master no one today doubts, but it's worth considering his particular achievement in this film: It contains a murder, two near-rapes, one near-suicide, serious threats to the lives of its protagonists, and the killing of a small dog, and yet it still retains its essential lightness of tone.

Monday, February 13, 2017

Master of the House (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1925)

Master of the House, Carl Theodor Dreyer's silent comedy-drama, is an ironic title, one attached to the film for its release in English-speaking countries. The original Danish title translates as Thou Shalt Honor Thy Wife, and the play by Sven Rindom on which it was based was called Tyrannens fald -- The Tyrant's Fall. It's also misleading to call it a comedy-drama, although it has moments of mild humor and a happy ending. The tone is seriocomic, or as the original title -- which is echoed in the film's concluding intertitle -- suggests, it's a moral fable. Viktor Frandsen (Johannes Meyer), the master of the house, is an ill-tempered bully, constantly berating his wife, Ida (Astrid Holm), who does everything she can to placate him. For example, she asks him whether he wants the meat she will serve him for lunch to be cold or warm. He answers, as usual irritably, as if he can't be bothered with such mundane matters, that he wants it cold. And then, later, when it's served, he snaps, "Couldn't you have found time to warm it up?" Life for Ida is constant drudgery, taking care of routine household chores, as well as looking after three children, the oldest of which is the pre-teen Karen (Karin Nellemose), whom Ida tries to spare from any of the harder chores that might roughen her hands. What little help Ida gets comes from Viktor's old nanny, known to the family as Mads (Mathilde Nielsen), who drops in to help Ida with the mending -- and to cast a disapproving eye on Viktor's bullying. Eventually, Mads arranges with Ida's mother (Clara Schønfeld) for Ida to escape from the household and rest. More worn out than she knew, Ida has a breakdown, and during her prolonged absence Mads takes over the household and whips Viktor into shape. The story arc is a familiar one -- we've seen it done on TV sitcoms and in Hollywood family comdies -- but it gains strength from the performances and from Dreyer's masterly control of the story and use of the camera. Although Viktor looks like a sheer monster at first, we gain understanding of him when we learn, well into the film, that he is out of work: His business has failed. His absence from the house during the day goes unexplained, although we see him walking the streets and dropping into a neighborhood bar. Nielsen, who had also played the role of Mads on stage, is a marvelous presence in the film, although Dreyer never questions whether, as a nanny who used to administer whippings to Viktor, she might not bear some responsibility for the way he turned out as a man. Best of all, the film gives us a semi-documentary glimpse of what daily life was like for a lower-middle-class family in 1920s Denmark (and presumably elsewhere that modern home appliances hadn't yet taken up some of the burden of housework). Dreyer's meticulous attention to detail -- he served as his own art director and set decorator -- extended to the construction of a four-walled set (walls could be removed to provide camera angles) with working plumbing and electricity and a functioning stove, and he makes the most of it. Master of the House is not quite the pioneering feminist film some would have it be: Ida is a little too sweetly passive even after Viktor reforms. But it's an important step in the growth of Dreyer's moral aesthetic and of his artistry as a filmmaker.

Sunday, February 12, 2017

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Yes, Vertigo is a great movie. No, it's not the greatest movie ever made, and to call it that does the film a disservice, inviting skeptics to investigate and overemphasize its flaws. The central flaw is narrative; Vertigo is at heart a preposterous melodrama, and the film raises questions that probably shouldn't be asked: How, for instance, did Scottie (James Stewart) get down from that gutter he was hanging onto after the cop fell to his death? How did Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) arrange to be at the top of that tower with his dead wife at the exact time when Madeleine (Kim Novak) and Scottie were climbing it? Why is the coroner (Henry Jones) so needlessly hostile to Scottie at the inquest? And so on, until the screenplay by Alec Coppel and Samuel A. Taylor reveals itself to be a thing of shreds and patches. If it is a great film, it's because it had a great director, and that almost no one will gainsay. Alfred Hitchcock drew a magnificent performance from Novak, an actress everyone else underestimated. (And one that he, initíally, didn't want: He was grooming Vera Miles for the role until she became pregnant.) He helped Stewart to one of the highlight performances of his career. He inspired Bernard Herrmann to compose one of the most powerful and evocative film scores ever written -- one whose expression of erotic longing is surpassed perhaps only by passages in Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. He worked with cinematographer Robert Burks to transform San Francisco and environs into one of the great movie sets. And he turned what could have been a routine thriller (which is what many critics thought it was at the time of its release) into one of the most analyzed and commented-upon films ever made. It will never be my favorite Hitchcock film: I place it below Notorious (1946), Rear Window (1954), North by Northwest (1959), and Psycho (1960) in my personal ranking of his greatest films, and I enjoy rewatching The 39 Steps (1935), The Lady Vanishes (1938), Foreign Correspondent (1940), and Strangers on a Train (1951) more than I do Vertigo. Yet I still yield to its portrayal of passionate obsession and its masterly blend of all the elements of cinema technology into a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk in which the whole transcends the sometimes indifferent parts.

Saturday, February 11, 2017

Almayer's Folly (Chantal Akerman, 2011)

|

| Stanislas Merhar in Almayer's Folly |

Capt. Lingard: Marc Barbé

Nina: Aurora Marion

Daïn: Zac Andrianasolo

Zahira: Sakhna Oum

Chen: Solida Chan

Director: Chantal Akerman

Screenplay: Chantal Akerman, Henry Bean, Nicole Brenez

Based on a novel by Joseph Conrad

Cinematography: Rémon Fromont

Production design: Patrick Dechesne

Film editing: Claire Atherton

Lots of movies -- think of Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950) and Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2014), for example -- begin with an incident and then flash back for the rest of the movie to explain it. So Chantal Akerman's Almayer's Folly begins with the camera following a Malaysian man into a nightclub where another man is lip-synching to Dean Martin's version of the song "Sway" as a group of women dances behind him. Suddenly the man who entered the club is on stage stabbing the lip-syncher. The music breaks off and all of the dancers flee the stage except one, who continues to perform the hula-like hand movements as if nothing had happened. We hear a voice call out, "Nina! Nina!" but she continues in her trance-like state for a while until she stops and begins to sing Mozart's setting of "Ave Verum Corpus" as the camera holds on her in closeup. The movie then flashes back to reveal that Nina is the daughter of the European Almayer and a Malaysian woman, Zahira. Almayer has come to Malaysia in search of his fortune -- he has heard of a gold mine ripe for the taking. Zahira and Nina live with him in a house by the river until one day his fellow European fortune-hunter, Captain Lingard, arrives to take Nina to the city to be educated: Almayer wants her to have the benefits and privileges of a European lady. Though Zahira and Nina flee into the jungle, Almayer and Lingard capture the girl. Nina is intensely unhappy at the school, scorned by the European girls, and when Lingard, who has been paying her tuition for Almayer, dies, she is expelled. She wanders the streets of the unnamed Malaysian city (the movie was actually filmed in Cambodia) and finally returns to Almayer's home. There she's seduced by Daïn, a shady young man who is supposedly helping Almayer find his fortune. Almayer recognizes his defeat and allows Nina and Dain to leave together. Unlike Wilder and the Coens, Akerman doesn't return to the opening scene at the film's end, but instead leaves us with two of her characteristic long takes: The first shows Almayer, Nina, and Daïn arriving at a sandbar where the river meets the sea to await the arrival of the boat that will take the two young people away; the camera lingers in a long shot as the boat arrives and Nina and Daïn swim out to it, then Almayer and his servant, Chen, push off into the river for their return home. The second long take is a closeup of the haggard, obviously very ill Almayer as he sits brooding in his decaying home, with Chen standing out of focus in the background. At the beginning of this take, Almayer says, "Tomorrow, I would have forgotten," a sentence that he repeats at the end after we watch the sun play across his face -- moving much more swiftly than it would in actuality -- and he talks about how the sun is cold and the river is black. By now, we have realized that the lip-syncher was Daïn and that Chen was his assassin. As for Almayer, we can only assume that he has died. Almayer's Folly, which Akerman loosely adapted from the early Joseph Conrad novel, is clearly a fable about the tragedy of colonialism, but she's not intent on laboring that topic. It's as much an attempt to prod the viewer into contemplating the mystery of character and identity as her more celebrated Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975) was, and by using less radical variations on the same techniques -- extended takes, minimized action -- she used in that film. Akerman developed a compelling and identifiable style, but there is a point at which style becomes mannerism. (We all want to be thought "stylish," and none of us want to be thought "mannered.") I think Almayer's Folly nears that point but doesn't fully reach it, largely because of the compelling performance of Merhar as Almayer, and because of Akerman's use of the setting, with the help of Rémon Fromont's cinematography and Claire Atheron's editing. She also makes fine ironic use of the Dean Martin song and the Mozart hymn, as well as the only non-diegetic music in the film, interludes filled with the erotic longing of Wagner's Prelude to Tristan and Isolde.

Friday, February 10, 2017

The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch, 1929)

|

| Jeanette MacDonald and Maurice Chevalier in The Love Parade |

Queen Louise: Jeanette MacDonald

Jacques: Lupino Lane

Lulu: Lillian Roth

War Minister: Eugene Pallette

Ambassador: E.H. Calvert

Master of Ceremonies: Edgar Norton

Prime Minister: Lionel Belmore

Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Screenplay: Ernest Vajda, Guy Bolton

Based on a play by Leon Xanrof and Jules Chancel

Cinematography: Victor Milner

Art direction: Hans Dreier

Film editing: Merrill G. White

Costume design: Travis Banton

Music: Victor Schertzinger

It irritates me a little to think that MGM, thanks largely to those That's Entertainment clip shows in the 1970s, is celebrated for its movie musicals, when in fact the genre was pioneered and perfected at other studios: Warner Bros. with its Busby Berkeley dance spectacles, RKO with its Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers cycle, and Paramount, where Ernst Lubitsch virtually invented the story musical with The Love Parade and subsequent re-teamings of Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald. (Oddly, today MacDonald is better known for her inferior and unsexy MGM teaming with Nelson Eddy.) MGM didn't achieve musical greatness until the end of the 1930s, when after the success of The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), the studio put its associate producer, Arthur Freed, in charge of the film musicals unit. True, MGM had won a best-picture Oscar with The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont, 1929), but that was a standard backstage musical, not one in which the songs and dances are fully integrated into the plot. Besides, it's almost unwatchable today, whereas thanks to the charm of Chevalier and the sexiness of MacDonald in her revealing pre-Code frippery, but most of all to what is known as "the Lubitsch touch," The Love Parade is still enjoyable. Lubitsch's "touch" as a director was based on a sly conviction that the audience would get the joke, usually a naughty one, and it was perfected during the silent era, when things had to be shown, not told. So the film opens with a mostly silent demonstration of why Count Alfred Renard has caused such a scandal with his dalliances in Paris that he has to be recalled to Sylvania and rebuked by Queen Louise. But this is also a film that wittily integrates sound into its sight gags, as the entire Sylvanian court eavesdrops on the burgeoning love of Alfred and Louise. The plot, derived by screenwriters Guy Bolton and Ernest Vajda from a French play, is standard, slightly sexist stuff about the prince consort, Alfred, feeling miffed by the fact that his marriage to the queen leaves him with nothing to do, but it's carried off well by the leads, as well as the saucy servants, Jacques and Lulu, and a court full of skilled character actors like Eugene Pallette, Edgar Norton, and Lionel Belmore. It's too bad that the song score by lyricist Clifford Grey and composer Victor Schertzinger isn't better -- there are too many reprises of "Dream Lover," for example -- but Lubitsch's staging compensates for its weakness.

Thursday, February 9, 2017

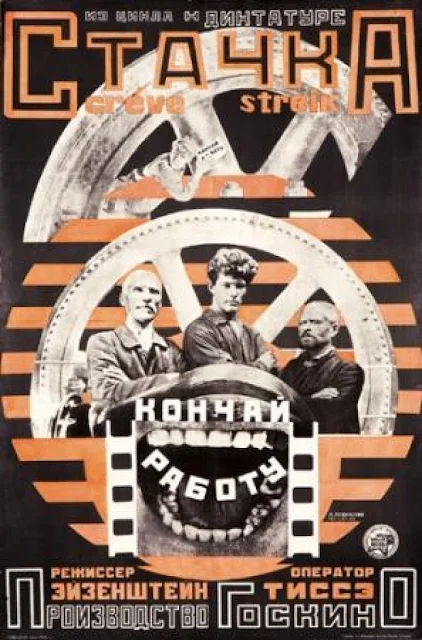

Strike (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

Subtle as a sledgehammer, Sergei Eisenstein's first feature film, Strike, demonstrates the dangerous ability of motion pictures to annihilate thought. With a torrent of images, almost as formidable as the fire hose blasts that mow down the protesting strikers in the fifth "chapter" of the film, the 27-year-old Eisenstein demonstrates a mastery of technique: fast-paced editing, frame-crowding action, provocative close-ups, and powerful montage. The film concludes with a bloodbath -- the "liquidation" of the strikers in their homes, intercut with scenes of cattle being slaughtered in an abattoir -- that makes the Odessa Steps massacre sequence in Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925) look like a Sunday picnic. The film veers from documentary realism in the factory scenes, to gross -- or perhaps Grosz, as in George Grosz -- caricature in its portrayal of the capitalist bosses as fat cigar-smoking men in silk top hats, to a baroque expressionism in the scenes involving the spies and provocateurs who betray the workers. Eisenstein never slackens for a moment -- it's an exhausting film. Is it a great film? That's one for the debaters, a conflict between those who believe in art as a servant of truth and those who believe in art as pure form. I can admire its technical virtues and historical significance, and even admit that it plays on my political sympathies for workers over capitalist bosses, while worrying that the effect of the film is to valorize a dangerous suppression of reason, the unhinged anti-humanism that ultimately betrayed the very revolution Eisenstein supported.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)