A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Carl Theodor Dreyer. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Carl Theodor Dreyer. Show all posts

Monday, February 13, 2017

Master of the House (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1925)

Master of the House, Carl Theodor Dreyer's silent comedy-drama, is an ironic title, one attached to the film for its release in English-speaking countries. The original Danish title translates as Thou Shalt Honor Thy Wife, and the play by Sven Rindom on which it was based was called Tyrannens fald -- The Tyrant's Fall. It's also misleading to call it a comedy-drama, although it has moments of mild humor and a happy ending. The tone is seriocomic, or as the original title -- which is echoed in the film's concluding intertitle -- suggests, it's a moral fable. Viktor Frandsen (Johannes Meyer), the master of the house, is an ill-tempered bully, constantly berating his wife, Ida (Astrid Holm), who does everything she can to placate him. For example, she asks him whether he wants the meat she will serve him for lunch to be cold or warm. He answers, as usual irritably, as if he can't be bothered with such mundane matters, that he wants it cold. And then, later, when it's served, he snaps, "Couldn't you have found time to warm it up?" Life for Ida is constant drudgery, taking care of routine household chores, as well as looking after three children, the oldest of which is the pre-teen Karen (Karin Nellemose), whom Ida tries to spare from any of the harder chores that might roughen her hands. What little help Ida gets comes from Viktor's old nanny, known to the family as Mads (Mathilde Nielsen), who drops in to help Ida with the mending -- and to cast a disapproving eye on Viktor's bullying. Eventually, Mads arranges with Ida's mother (Clara Schønfeld) for Ida to escape from the household and rest. More worn out than she knew, Ida has a breakdown, and during her prolonged absence Mads takes over the household and whips Viktor into shape. The story arc is a familiar one -- we've seen it done on TV sitcoms and in Hollywood family comdies -- but it gains strength from the performances and from Dreyer's masterly control of the story and use of the camera. Although Viktor looks like a sheer monster at first, we gain understanding of him when we learn, well into the film, that he is out of work: His business has failed. His absence from the house during the day goes unexplained, although we see him walking the streets and dropping into a neighborhood bar. Nielsen, who had also played the role of Mads on stage, is a marvelous presence in the film, although Dreyer never questions whether, as a nanny who used to administer whippings to Viktor, she might not bear some responsibility for the way he turned out as a man. Best of all, the film gives us a semi-documentary glimpse of what daily life was like for a lower-middle-class family in 1920s Denmark (and presumably elsewhere that modern home appliances hadn't yet taken up some of the burden of housework). Dreyer's meticulous attention to detail -- he served as his own art director and set decorator -- extended to the construction of a four-walled set (walls could be removed to provide camera angles) with working plumbing and electricity and a functioning stove, and he makes the most of it. Master of the House is not quite the pioneering feminist film some would have it be: Ida is a little too sweetly passive even after Viktor reforms. But it's an important step in the growth of Dreyer's moral aesthetic and of his artistry as a filmmaker.

Tuesday, November 22, 2016

The Passion of Joan of Arc (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1928)

|

| Renée Jeanne Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc |

*So far, Filmstruck hasn't moved much beyond streaming on the computer, though it's supposed to be included on Roku early next year. In my household, with two others competing for bandwidth, this meant that I had frequent interruptions as the film refreshed itself. Oddly enough, I didn't mind as much as I usually would, because Dreyer's images are so compelling that I was content to pause and study them.

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

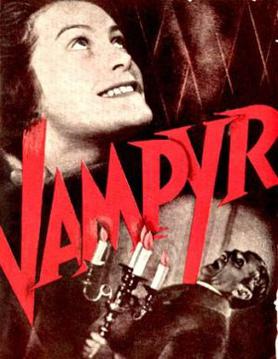

Vampyr (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1932)

In the catalog of vampire movies, Vampyr is probably the second scariest after Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922). Which is odd, because its narrative, based by Dreyer and co-writer Christian Jul on a story be Sheridan Le Fanu, is fractured and almost incoherent and its characterization scattered. But you get the feeling that Dreyer himself really believed in the malevolent creatures he put on film, not surprising since most of Dreyer's films were in one way or another about faith. One story has it that the look of the film came about accidentally: Cinematographer Rudolph Maté shot an early sequence slightly out of focus, and when he apologetically showed it to Dreyer, the director insisted that was exactly how he wanted the film to look. Maté consequently shot many sequences through gauze. Accident also dictated some of the story: Dreyer insisted on location shooting, and in scouting for places to shoot, discovered the flour mill, giving him the idea for the scene in which the doctor meets his rather gruesome end. The lead character, Allen Grey, was played by a non-professional, Nicolas de Gunzburg, under the pseudonym Julian West -- Gunzburg was also the principal financial backer of the film. Most of the rest of the cast were non-professionals as well, and the sense that Vampyr is the result of serendipitous filmmaking has given the film a certain cachet over the years, especially with filmmakers and critics struggling with the restrictions that the corporate bottom line places on their art. To my mind, Vampyr is a collection of fascinating, disturbing images -- the man with the scythe crossing the river, the play of eerie shadows, the unusually successful double exposure that gives us Allen Grey's out-of-body experience, the sequence in which Grey sees himself in a coffin, and so on. But it seems to me to be brilliant parts in search of a satisfying whole.

Tuesday, June 14, 2016

Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964)

Imagine Gertrud as a Hollywood "women's picture" of the 1940s or '50s, with Olivia de Havilland, perhaps, as Gertrud, and Claude Rains as her husband, Montgomery Clift as her young lover, and Walter Pidgeon as the old flame who comes back into her life. It's not hard to do, given that the play by Hjalmar Söderberg on which Carl Theodor Dreyer based his film has all the elements of the genre: a woman trapped in a sterile marriage; an ardent young lover who appeals to the artist trapped in her; another man who represents the road not taken that might have led her to fulfillment if she hadn't discovered that he was more committed to his work than to her. And it ends the way the Hollywood film might have: After Gertrud has rejected those three lovers and gone off to Paris with yet another man -- George Brent, perhaps -- who seemed to give her the opportunity to find herself, we see them reunite 30 or 40 years later, when she has settled into a sadly contented solitary life. There would have been a Max Steiner or Alfred Newman score to draw tears at the crisis moments -- as when, for example, Gertrud discovers that her young lover has boasted of his affair with her at a party also attended by the old flame. But this is a "women's picture" of ideas, largely about the nature of love and the way we can be deceived in the pursuit of it. And there are no melodramatic moments, merely extended conversations in which the participants rarely, if ever, make eye contact. As Gertrud, Nina Pens Rode maintains a gaze into the middle distance, rarely even blinking, whether she's telling her husband (Bendt Rothe) that she's leaving him, declaring her love for the young musician (Baard Owe) who later boasts of his conquest, or reminiscing about their past together with her old flame (Ebbe Rode). But the faint flicker of thought and emotion always plays over her face, as Henning Bendtsen's camera gazes steadily at her. It is, for those raised on the Hollywood version, something of a trying and even boring film, but for those who understand what Dreyer is doing -- grabbing the viewer's eye and keeping it trained on the characters, through long, long takes and subtle camera moments -- it creates a psychological tension that is unnerving. Dreyer makes more conventional directors' work seem frantic and frivolous.

Monday, June 13, 2016

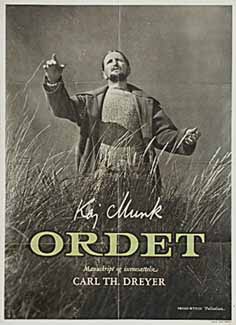

Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

As a non-believer, I find the story told by Ordet objectively preposterous, but it raises all the right questions about the nature of religious belief. Ordet, the kind of film you find yourself thinking about long after it's over, is about the varieties of religious faith, from the lack of it, embodied by Mikkel Borgen (Emil Hass Christensen), to the mad belief of Mikkel's brother Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) that he is in fact Jesus Christ. Although Mikkel is a non-believer, his pregnant wife, Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), maintains a simple belief in the goodness of God and humankind. The head of the Borgen family, Morten (Henrik Malberg), regularly attends church, but it's a relatively liberal modern congregation, headed by a pastor (Ove Rud), who tries to be forward-thinking: He denies the possibility of miracles in a world in which God has established physical laws, although he doesn't have a ready answer when he's asked about the miracles in the Bible. When Morten's youngest son, Anders (Cay Kristiansen), falls in love with a young woman, her father, Peter (Ejner Federspiel), who belongs to a very conservative sect, forbids her to marry Anders. Then everyone's faith or lack of it is put to test when Inger goes into labor. The doctor (Henry Skjaer) thinks he has saved her life by aborting the fetus -- we are told that it has to be cut into four pieces to deliver it -- but after he leaves, Inger dies. As she is lying in her coffin, Peter arrives to tell Morten that her death has made him realize his lack of charity and that Anders can marry his daughter. And as if this doesn't sound conventionally sentimental enough, the film ends with Inger, who has died in childbirth, being restored to life with the help of Johannes and the simple faith of her young daughter. Embracing Inger, Mikkel now proclaims that he is a believer. The conundrum of faith and evidence runs through the film. For example, if the only thing that can restore one's faith is a miracle, can we really call that faith? What makes Ordet work -- in fact, what makes it a great film -- is that it poses such questions without attempting answers. It subverts all our expectations about what a serious-minded film about religion -- not the phony piety of Hollywood biblical epics -- should be. Dreyer and cinematographer Henning Bendtsen keep everything deceptively simple: Although the film takes place in only a few sparely decorated settings, the reliance on very long single takes and a slowly traveling camera has a documentary-like effect that engages a kind of conviction on the part of the audience that makes the shock of Inger's resurrection more unsettling. We don't usually expect to find our expectations about the way things are -- or the way movies should treat them -- so rudely and so provocatively exploded.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)