A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, April 13, 2017

Through a Glass Darkly (Ingmar Bergman, 1961)

Ingmar Bergman's Through a Glass Darkly is usually grouped with his films Winter Light (1963) and The Silence (1963) as a kind of trilogy about the search for God, though Bergman denied having any intent to make a trilogy. It remains one of his most critically praised films, winning an Oscar for best foreign language film and receiving a nomination for Bergman's screenplay. But there are many, like me, who find it talky and stagy, despite Sven Nykist's beautiful cinematography and the effective use of location shooting on the island of Fårö in the Baltic. Some of the staginess, I think, comes from the casting of such familiar members of Bergman's virtual stock company as Harriet Andersson, Max von Sydow, and Gunnar Björnstrand. Andersson plays Karin, a woman just out of a mental hospital where she has recovered from a recent bout with what seems to be schizophrenia. She is married to Martin (von Sydow) and they have come to stay on the island with her father, David (Björnstrand), and her younger brother, Minus (Lars Passgård). David is distracted by his attempt to finish a novel, and both of his children rather resent his preoccupation. Martin confides in David that although Karin seems to have recovered, the doctors say that her illness is incurable -- a revelation that David records in his diary. Of course, Karin reads the diary, which precipitates a crisis, during which, among other things, she seduces her own brother. At the climax of the film, Karin has a vision of God as a giant spider that attempts to rape her. After she and Martin are taken away to the hospital, David has a moment alone with Minus, whom he assures that God and love are the same thing, and that their love for Karin will help her. Minus seems consoled by this thought, but perhaps even more by the fact that he has actually had a connection with his father: "Papa spoke to me" are the last words of the film. This resolution of the film's torments feels pat and theatrical and even upbeat, which may be why Bergman went on to make the much darker films about religious faith that constitute the rest of the trilogy. But it also suggests to me why I find Bergman's films so much less satisfying than those of Robert Bresson and Carl Theodor Dreyer, both of whom wrangled with God and faith in their films. Bresson and Dreyer liked to use unknown actors, and some of the familiarity we have with Bergman's players from other films distances us from the characters. We watch them acting, not being. When Bresson is dealing directly with religious faith in a film like Diary of a Country Priest (1951) or Dreyer is telling a story about a literal resurrection in Ordet (1955), we are forced to confront our own beliefs or absence of them. Bergman simply presents faith as a dramatic problem for his characters to work out, whereas Bresson and Dreyer drag us into the messy actuality of their characters' lives.

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984)

|

| Nastassja Kinski and Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas |

Tuesday, April 11, 2017

Shall We Dance (Mark Sandrich, 1937)

This was the seventh teaming of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, and the fatigue is beginning to show, despite a score by George Gershwin and songs with his brother Ira. Shall We Dance is marred by a tired script -- credited to Allan Scott and Ernest Pagano -- that reworks the familiar pattern: The Astaire and Rogers characters meet cute, feel an attraction to each other that they resist, find themselves in farcical misunderstandings, and several spats, songs, and dances later assure themselves that they are in love. In this one, Astaire plays a faux-Russian ballet dancer called Petrov -- he's actually Pete Peters from Philadelphia, Pa. -- who really wants to be a tap dancer. The idea of Astaire as a danseur noble is absurd from the start, and Astaire knew it -- he had turned down the lead in the 1936 Broadway production of the Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart musical On Your Toes, which like Shall We Dance centers on a production that combines ballet with Broadway-style dance. Gershwin, too, was not entirely happy about the idea of composing ballet music, but both men were eventually persuaded to go along with the idea. The plot gimmick is that Peters/Petrov has fallen for tap dancer Linda Keene, who initially spurns him, and through a series of mishaps the rumor gets started that the two are secretly married. After much ado, they really get married so she can divorce him and put a stop to the rumors, but by then they of course have really fallen in love. One problem is that, unlike the best Astaire-Rogers films, Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935) and Swing Time (George Stevens, 1936), the songs in Shall We Dance don't grow organically out of the screenplay. They have to be wedged in, like Astaire's number "Slap That Bass," which takes place in the engine room of the ocean liner on which Petrov and Linda are traveling -- one of the oddest of the Big White Sets for which the Astaire-Rogers musicals were famous: It's the cleanest engine room ever seen. The biggest Astaire-Rogers dance duet in the film is "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off," which is performed on roller skates in a park when Petrov and Linda try to evade pursuing reporters; it, too, seems designed more to get Astaire and Rogers on skates than to contribute to the plot. On the other hand, there's an obvious missed opportunity for a romantic duet to the Oscar-nominated song "They Can't Take That Away From Me," which Astaire sings to Rogers, but he doesn't follow through by dancing with her. He does dance to a few bars of the song when it's reprised later in the film, but his partner is Harriet Hoctor, a dancer whose specialty was a deep back-bend that she performed while en pointe. There's a sequence in which Hoctor does her thing while dancing backward toward the camera, which she is facing, that's flat-out creepy. Astaire-Rogers film regulars Edward Everett Horton and Eric Blore are on hand to do their usual fussbudget routines. Blore's bit in which he tries to tell Horton over the phone that he's been arrested and is at the Susquehanna Street Jail, constantly being interrupted in his attempts to spell "Susquehanna," is the film's funniest moment.

Monday, April 10, 2017

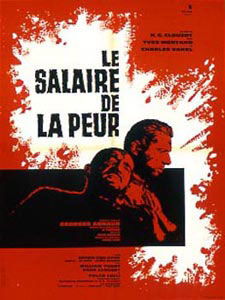

The Wages of Fear (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1953)

With John Huston's The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969), Henri-Georges Clouzot's The Wages of Fear forms an unholy trinity of adventure films. All three are about soldiers of fortune in Latin American countries seen as ripe for the pickings by predatory outsiders. Clouzot's film is probably the most deeply cynical of the three: Houston at least lets two of his adventurers survive, and Peckinpah's bunch at least shows some sympathy for the exploited poor. But from the opening of Clouzot's film, in which a half-naked child is seen tormenting some cockroaches (a scene Peckinpah borrowed for his film's opening), we are in hell. The unnamed country is being plundered by the Southern Oil Company, known by the acronym SOC, pronounced "soak." The S and the O, however, suggest Esso, the old trademark of Standard Oil before it and Mobil morphed into the double anonymity of Exxon. An oil well is on fire 300 miles away from the SOC headquarters, which lie on the outskirts of an impoverished village, and the easiest way to deal with the fire is to seal it off with explosives. So the foreman at the headquarters, Bill O'Brien (William Tubbs), proposes sending a couple of trucks cross-country, laden with nitroglycerin. Union drivers would balk at such dangerous work, so the company hires some of the local layabouts: Mario (Yves Montand), a swaggering Corsican; Jo (Charles Vanel), a French gangster from Paris; Luigi (Folco Lulli), an Italian who has just learned that he has a terminal lung illness from his work handling cement for SOC; and Bimba (Peter van Eyck), a German who survived forced labor in a salt mine under the Nazis. All three have been idling in the village waiting for the big break that will allow them to leave, and this seems to be it. Desperation at getting out is so intense that one of the men who vie for the job commits suicide after he fails to land it. The journey is, to say the least, harrowing, and Clouzot, who adapted the screenplay with Jérôme Géronimi from a novel by Georges Arnaud, makes the most of every nail-biting moment of it. As a director, Clouzot is as smart in what he chooses not to show us and in what he does. Jo, for example, is not the first choice as a driver: O'Brien goes with a younger man. But when that man doesn't show up on the morning of departure, Jo takes his place. We don't see what Jo did to eliminate or delay his rival, but we're sure it wasn't good. And when one of the trucks explodes, we don't see the buildup to or the cause of the explosion: We witness it from a distance, and then join the surviving truck drivers as they come upon the scene, which they treat as just another hazardous obstacle on the road. The Wages of Fear was heavily cut on its first American release: The portrayal of American capitalism didn't sit well in the era of HUAC investigations. Clouzot's nihilism in The Wages of Fear sometimes feels a little heavy: One character actually dies with the word "nothing" on his lips. The screenplay for The Wages of Fear lacks the polished wit of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which also contains the great performances of Humphrey Bogart, Walter Huston, and the undervalued Tim Holt. And The Wild Bunch displays Peckinpah's great narrative drive and unequaled handling of action sequences. But Clouzot's film easily belongs in their company, and its uncompromising darkness makes many think it the best of the three.

Sunday, April 9, 2017

That Man From Rio (Philippe de Broca, 1964)

With its nonstop silliness, Philippe de Broca's That Man From Rio became a big international commercial success, but more surprising, it got an Oscar nomination for its screenplay, written by de Broca with Jean-Paul Rappeneau, Ariane Mnouchkine, and Daniel Boulanger. It's usually characterized as a spoof of James Bond films, with their glamorous locations and over-the-top action sequences, but if a spoof is intended to laugh its target out of existence, That Man only whetted audiences' appetites for more of the same. One of its stars, Adolfo Celi, who pays the unscrupulous, fabulously wealthy Mário de Castro, turned up the following year as the unscrupulous, fabulously wealthy Bond villain Emilio Largo in Thunderball (Terence Young, 1965). And it's easy to see touches of That Man From Rio in later action-adventure films, such as the Indiana Jones series, which like de Broca's film centered on archaeological treasure hunting. In That Man From Rio, the location of a priceless treasure is discovered by lining up the sun's rays through the lens in an ancient statue, just as Indiana Jones uses the sun's rays and an ancient artifact to discover the location of the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg, 1981). Jean-Paul Belmondo's Adrien picks up the help of a Rio shoeshine boy called Sir Winston (Ubriacy De Oliviera), just as Harrison Ford's Indy picks up a kid sidekick called Short Round (Jonathan Ke Quan) in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (Spielberg, 1984). Still, That Man From Rio stands on its own for its goofy energy, most of which is supplied by Belmondo, who with his ex-boxer's mug and physique is entirely credible flinging himself into whatever improbable situation he is called on to fight (or swim or climb or swing from vines) his way out of. Françoise Dorleac is the giddy heroine, Agnès, who spends much of the first part of the movie drugged out of her mind and never seems to find her way fully back to sobriety. It's only in retrospect -- 53 years worth of retrospect -- that the film turns sour. Today, we can see it as part of the playing out of a post-colonial environmental nightmare. There are no slums to be seen in the film's Rio: Sir Winston lives in a neatened up favela nothing like the one you see in City of God (Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund, 2002). The city of Brasília, still under construction when the film was made, is treated as a setting for Belmondo's stunts and for elaborate parties, though perhaps some of the bleakness and sterility of its Robert Moses-style urban-planning megalomania is hinted at. And at the end our hero and heroine are "rescued" by construction crews blasting and bulldozing their way through the rainforest, constructing highways that will connect to the country's new capital. There's no apparent suggestion that this constitutes a kind of environmental rape, although the villainous archaeologist (Jean Servais) is buried along with what might have been a valuable site. De Broca does allow us a glimpse of an Indian family looking on in astonishment at the raw earth uncovered by the bulldozers pushing their way through what must have been their neighborhood. It's a fleeting moment, however, one quickly passed over as Adrien and Agnès ride a truck back to civilization.

Saturday, April 8, 2017

Down by Law (Jim Jarmusch, 1986)

At the end of Jim Jarmusch's Mystery Train (1989), his young Japanese tourists set out for New Orleans, where the writer-director had been three years earlier to make Down by Law. As he did with Memphis for Mystery Train, Jarmusch imagined the city and wrote his screenplay before he ever set foot in New Orleans, and the resulting film is a kind of fleshing out of his imagination. Jarmusch's New Orleans is a construct of legend and myth, then, not to be taken literally any more than one would a fairy tale -- which is what Jarmusch has called Down by Law. He imagines New Orleans as a city of musicians, prostitutes, and tourists, and he casts his three central characters in the mode of each: Tom Waits as Zack, an out-of-work disc jockey; John Lurie as Jack, a small-time pimp; and Roberto Benigni as Roberto, or Bob, an Italian wandering the city to soak up American idiom, which he dutifully writes down in his notebook. But if Jarmusch's New Orleans is an imaginary construct, it is grounded in a kind of visual reality, provided at the film's beginning by Robby Müller's camera as it roams the streets of the city, showing the signs of decay it exhibited even before Katrina. And the scenes that establish Zack and Jack are rooted in a sordid poverty, as Zack is kicked out of their apartment by his girlfriend, Laurette (Ellen Barkin), and Jack is lured into a trap in which he is arrested with an underage prostitute he has never met before. (Bob makes a kind of cameo appearance in a scene with Zack, thoroughly stoned and out on the street, who tells him to "buzz off" -- a phrase Bob records in his notebook.) After Zack is tricked into driving a car that has a body in the trunk, he joins Jack in the Orleans Parish Prison, where things look like they can't get any worse. But then Bob joins them in their cell, having been arrested for killing a man with a billiard ball in a pool hall fracas, and the film turns on a dime from a noirish study of the underclass into an off-beat comedy that, among other things, validated Benigni's Italian reputation as a comic genius. Here he's a catalyst, stirring Waits and Lurie into performances that raise their characters from sleazy to endearing. But the real star of the film for me is Müller, whose black-and-white cinematography also elevates the sordid into the beautiful. It becomes a film of textures, from the silken skin of a nude prostitute to the etched graffiti on a prison cell wall to the layer of duckweed on the surface of a bayou. In an interview, Müller has commented on how black-and-white has an effect of subtraction: Color gives you more information than you need, while black-and-white helps you concentrate on particulars. Down by Law has been criticized for its slowness, and Jarmusch certainly lets the tension slack a little, but even when there's nothing much going on, Müller's images keep the pulse of life steady.

Friday, April 7, 2017

Strangers on a Train (Alfred Hitchcock, 1951)

Strangers on a Train and North by Northwest (1959) are the best of Alfred Hitchcock's "wrong man" thrillers, in which the protagonist is suspected of a crime he didn't commit and spends most of the film trying to prove his innocence. They have something else in common: Both involve seduction scenes that take place on a train, except that in the latter film the seduction, of Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) by Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), is conventionally heterosexual. It's the gay subtext that marks Strangers on a Train from the very beginning, when we watch the feet of Guy Haines (Farley Granger) and Bruno Antony (Robert Walker) as they board the train and eventually bump up against each other in the club car. It's Bruno's flamboyance, especially the gleaming white of his brown-and-white spectator shoes, that we notice first, before we see his lobster-patterned tie and the gold tie clasp that proclaims his name. Even the straightest viewer gets it: Bruno is cruising. And he lights upon the handsome athlete, Guy. Bruno is blatant, and he's more than a bit obnoxious, as he invades Guy's space and continues to talk after Guy has signaled that he'd be happy to be left alone with his book. Yet somehow Guy, who on the surface of it seems the kind of man who would brush Bruno aside swiftly, lets himself be talked into having lunch in Bruno's compartment. Only when Bruno makes his shocking tit-for-tat murder proposal does Guy make his exit. I think that Hitchcock is suggesting that Guy is at least intrigued by the possibility of hooking up with another man. Guy's sexuality is brought into question by his marriage to the promiscuous Miriam (Kasey Rogers, then billed as Laura Elliott) and by the obvious motive of political ambition that has led him to the daughter of a senator, Anne Morton (Ruth Roman), who looks older than he does. (Roman was, in fact, three years older than Granger.) Hitchcock goes about as far as he can under the Production Code in making his characters gay, but even this little helps heighten the paranoia that's haunting Guy. It was 1951, after all, when homosexuality was still considered "deviance" and ferreting it out became an obsession of the FBI and other watchdog groups. That said, Strangers on a Train works even if you prefer to ignore subtext and see Guy and Bruno as a conventional hero and villain. Walker's performance is one of the best in any Hitchcock film, and his failure to be nominated for it by the Academy remains a marked injustice. Strangers received only one nomination, a deserved one: for Robert Burks's cinematography, the first of 12 collaborations with Hitchcock. Also overlooked were editor William H. Ziegler and special effects creator Hans F. Koenekamp, who gave us one of the most exciting scenes in the movies: the runaway merry-go-round. Hitchcock was deservedly proud of the film, having fought with his first choice as screenwriter, Raymond Chandler, who retained credit after he was fired and the script was rewritten, under Hitchcock's guidance, by Czenzi Ormonde and the uncredited Ben Hecht and Alma Reville, who followed an initial adaptation by Whitfield Cook of Patricia Highsmith's novel. Roman's casting is the film's major weakness: The studio forced Hitchcock to cast her, and he made no attempt to turn her into a real actress. She quickly exhausts her limited supply of anxious looks, practically the only ones the screenplay gives her; perhaps only the fear of getting lipstick on her teeth kept her from actually biting her lip. But the film launched what some think was Hitchcock's greatest decade, culminating in the amazing trifecta of Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest, and Psycho (1960).

Thursday, April 6, 2017

I Vinti (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1953)

|

| Fay Compton and Peter Reynolds in I Vinti |

Wednesday, April 5, 2017

The English Patient (Anthony Minghella, 1996)

The "prestige motion picture" is a familiar genre: It's typically a movie derived from a distinguished literary source or a biopic about a distinguished historic figure, with a cast full of major actors, but designed not so much to advance the art of film as to attract critical raves and awards -- particularly Oscars. There are plenty of examples among the best-picture Oscar winners: A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966), Chariots of Fire (Hugh Hudson, 1981), Gandhi (Richard Attenborough, 1982), Amadeus (Milos Forman, 1984), Out of Africa (Sydney Pollack, 1985), and The Last Emperor (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1987). (The 1980s seemed to be particularly dominated by prestige-seekers.) The trouble is that once the initial attraction of these films has faded, few people seem to remember them fondly or want to watch them again. I'd rather watch The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966) today than sit through A Man for All Seasons, and I would say the same for Atlantic City (Louis Malle, 1981), Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), Starman (John Carpenter, 1984), Prizzi's Honor (John Huston, 1985), and Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987) when put in competition with the prestige best-picture winners of their respective years. So I watched The English Patient last night to test my theory that prestige movies don't hold up over time. It fits the category precisely: It's based on a Booker Prize-winning novel by Michael Ondaatje; it has a distinguished cast, three of whom were nominated for acting Oscars, including Juliette Binoche, who won; it earned raves from The New Yorker, the New York Times, and Roger Ebert; it raked in 12 Oscar nominations and won nine of them -- picture, supporting actress, director Anthony Minghella, cinematographer John Seale, art direction, costumes, sound, film editor Walter Murch (who also shared in the Oscar for sound), and composer Gabriel Yared. And sure enough, there are films from 1996 that I'd rather watch again than The English Patient, including Fargo (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen), Lone Star (John Sayles), and Trainspotting (Danny Boyle). But I also have to say that of all the "prestige" best picture winners, The English Patient makes the best case for the genre. It's a good movie, with a mostly well-crafted screenplay by Minghella from a book many thought unfilmable, though it still tries to carry over too much from the novel, such as the character of David Caravaggio (Willem Dafoe), whose function in the film, to provoke Almásy (Ralph Fiennes) into uncovering his story, could have been served equally well by Hana (Binoche). But the performances still seem fresh and committed. Binoche, though designated a supporting actress, carries the film by turning Hana into a kind of central consciousness. I was surprised at how much heat is generated by Fiennes and Kristin Scott Thomas as Katharine, considering that they are both usually rather icy performers. There are some beautifully staged scenes, like the one in which Kip (Naveen Andrews) "flies" Hana so she can view the frescoes high in a church. And Murch's sound editing gives the film a marvelous sonic texture, starting with the mysterious clinking sounds at the film's beginning, which are then revealed to be the bottles carried by an Arab vendor of potions. Murch's ear and Seale's eye make the film an enduring audiovisual treat.

Tuesday, April 4, 2017

Jean de Florette / Manon of the Spring (Claude Berri, 1986)

There's no good reason why Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring should have been two films rather than one. They were shot together over the course of seven months, but released separately, Manon following Jean after about three months. Shown together as one film, they would total some 230 minutes -- only a bit longer than Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959) at 212 minutes or Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962) at 222 minutes. But the length of those films seems consistent with their epic pretensions, whereas Jean/Manon together amount to a domestic melodrama -- an entertaining one, with a beautiful Provençal setting, but far from an epic. Their separate releases feel a bit like a con -- as in economics. Films of that blockbuster length are a drag on the exhibitor, who must schedule fewer showings per day, so it probably made sense to release Jean, which unabashedly announces at the end that it's "part one," to whet an appetite for Manon, whose posters announced it as the second part of Jean de Florette. Voilà! double the box office take. In fact, Manon of the Spring had been filmed before, by Marcel Pagnol in 1952, and it had been a long film, as much as four hours, before being cut by the distributor. Pagnol was so upset by this experience that he turned the screenplay into a novel, L'Eau des Collines, adding the story of Manon's father, Jean, which had been only a backstory in his film. And it's this novel that Claude Berri decided to adapt into his two films. The problem I see, having just watched Berri's films back to back, is that there's not quite enough material for two. Jean de Florette is an overextended prequel, introducing the characters of César Soubeyran (Yves Montand) and his nephew Ugolin (Daniel Auteuil), and their villainous attempt to cut off the water supply to Jean (Gérard Depardieu), the newcomer who inherits the estate they covet. Or perhaps Manon of the Spring is a thinly developed sequel, in which Jean's daughter, Manon (Emmanuelle Béart), avenges her father. If Jean had been trimmed of some of the scenes of Jean raising rabbits and Manon of some of the shots of Manon gamboling with her goats in the hills -- as well as the romantic subplot involving the new village schoolteacher (Hippolyte Girardot) -- both stories could have fitted nicely into one movie. Manon climaxes with a scene in which César learns an uncomfortable truth about Jean's parentage, but Berri and co-screenwriter Gérard Brach drag the film out after that revelation, which should have been left to make its impact. Still, Berri's films have much to recommend them, especially the performances of Montand, Auteuil, and Depardieu (the last is sorely missed in the second film) and the beautiful cinematography of Bruno Nuytten. Jean-Claude Petit's score makes good use of themes from the overture to Giuseppe Verdi's La Forza del Destino.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)

.jpg)