Il Grido is Michelangelo Antonioni's last venture into something like neorealism before he moved away from conventional narrative film into the great trilogy of

L'Avventura (1960),

La Notte (1961), and

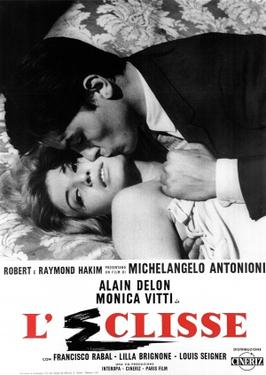

L'Eclisse (1962) that enthralled critics and tantalized audiences with their emotionally numb protagonists, unresolved stories, and symbolic use of the urban environment as a correlative for the alienation of the characters. Which is not to say that Antonioni doesn't make powerful symbolic use of the environment in which the events of

Il Grido take place. It's set in the Po Valley near Ferrara, where Antonioni grew up. It's a flat, muddy, marshy, malarial environment for a story about Aldo (Steve Cochran), who has suddenly had all of his ideas about what it means to be a man thrown into question. For seven years, he has lived with Irma (Alida Valli), working as a mechanic in a sugar refinery and helping raise their daughter, Rosina (Mirna Girardi). Irma's husband left her to seek work in Australia, and when word comes that he has died, Aldo suggests that they legitimize their relationship. But Irma wants to move on, and when she tells Aldo that she's found someone else, he beats her in the public streets, then quits his job, takes Rosina, and goes on the road in search of work. His odyssey puts him in contact with three other women, all of whom turn out to be stronger than the burly, macho Aldo. He goes to see an old girlfriend, Elvia (Betsy Blair), who still loves him but quickly discovers that she's better off without him around. He and Rosina hitch a ride on a petroleum tanker that drops him off at a filling station run by Virginia (Dorian Gray), with whom he begins an affair that makes him realize Rosina would be better off with her mother. But after sending her home, he decides he's unhappy being a kept man and sets off in search of work. He takes up for a while with Andreina (Lyn Shaw), a prostitute, but finally, depressed at being unemployed, returns to the town where he lived with Irma and finds her nursing a new baby, the refinery shut down, and the town being threatened with demolition to build an airfield for a military installation. When Irma learns of his return, she goes in search of him and finds him at the refinery, where he climbs to the top of a tower and falls to his death -- whether suicide or the consequence of the fatigue and weakness he exhibits, we're left to decide. Cochran never became the Hollywood leading man he sought to be, mostly finding tough-guy supporting roles in films like

The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946) and

White Heat (Raoul Walsh, 1949), but he gives an intensely physical performance in

Il Grido. He's dubbed, of course, as is Blair, but post-synchronized dialogue was common in Italy at the time, and even Dorian Gray, who was Italian, was dubbed in

Il Grido by no less than Monica Vitti, Antonioni's muse-to-be.

Il Grido can be faulted as melodramatic, which the piano score by Giovanni Fusco tends to emphasize, but its compensatory strengths lie in Cochran's performance and in the use of the bleak, muddy landscape by Antonioni and cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo.