|

| Chantal Akerman in Je Tu Il Elle |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Je Tu Il Elle (Chantal Akerman, 1974)

Monday, May 15, 2017

The Woman on the Beach (Jean Renoir, 1947)

Imagine The Woman on the Beach if Jean Renoir had made it in France with, say, Simone Signoret, Gérard Philipe, and Jean Gabin, and perhaps you can see what I mean when I say it's the best example of the kind of pressures Renoir felt during his war-imposed exile in Hollywood. Although the war was over, Renoir was under contract to RKO for two more pictures, but after the failure of The Woman on the Beach, the studio canceled the contract, so it was his last American film. If he had made the film in France, he wouldn't have been subjected to the heavy-handedness of Production Code censorship, which almost killed the film from the outset when the Code administrator, Joseph I. Breen,* declared the story, adapted from a novel by Mitchell Wilson, "unacceptable ... in that it is a story of adultery without any compensating moral values." Somehow Breen was persuaded to give in. But Renoir also had to put up with the studio star system, which required performers to look glamorous and handsome even in the most adverse situations. Even though Joan Bennett's character, Peggy Butler, spends a lot of time on the beach doing things like gathering firewood, her hair and makeup are always perfect. After an unfavorable preview of the film, the studio forced reshoots and made some drastic cuts -- the existing version is only 71 minutes long -- that displeased Renoir. What we have now is a sometimes fascinating, sometimes incoherent film. There's an on-again, off-again relationship between a Coast Guard officer, Scott Burnett, played by Robert Ryan, and a young woman named Eve, played by the starlet Nan Leslie, that serves no essential function in the story. Scott's nightmares about being on a sinking ship during wartime and an encounter on the beach with a ghostly woman who looks something like Eve loom large in the early part of the film but then mysteriously vanish along with any other symptoms of the PTSD Scott supposedly suffers from. The focus of the story is on Scott's affair with Peggy -- they apparently have sex in a shipwreck that has washed up on the beach -- and his suspicions about Peggy's husband, Tod (Charles Bickford), a famous painter who is now blind, the result of a fight in which Peggy threw something that severed his optic nerve. But Scott thinks Tod is faking his blindness and puts him to the test, which Tod passes by falling off a cliff without doing himself serious harm. There's a good deal of overheated dialogue: "Peg, you're so beautiful ... so beautiful outside, so rotten inside." In the end, there's a conclusion in which nothing is concluded: Scott seemingly tries but fails to drown both himself and Tod; Tod sets fire to the cabin that contains his cherished surviving paintings; he and Peggy set off for New York; and Scott retires from his commission in the Coast Guard. Some of this might have made emotional sense in a better-crafted film, one not subject to the tinkering and scrubbing that the studio and the censors enforced. Still, Bennett, Ryan, and Bickford perform with conviction, and there are those who find even the film's chaotic presentation of erotic entanglements compelling.

*Renoir doesn't seem to have nursed any hard feelings against Breen: He cast his son, Thomas E. Breen, in a key role in The River (1951).

*Renoir doesn't seem to have nursed any hard feelings against Breen: He cast his son, Thomas E. Breen, in a key role in The River (1951).

Sunday, May 14, 2017

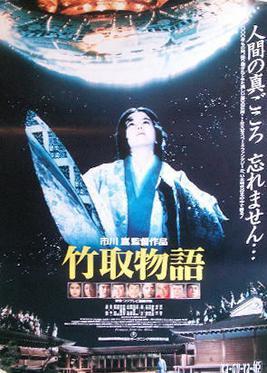

Princess From the Moon (Kon Ichikawa, 1987)

In eighth-century Japan, a man (Toshiro Mifune) and his wife (Ayako Wakao) are mourning the death of their 5-year-old daughter, Kaya. They live beside a forest of bamboo, whose stalks the man cuts and turns into baskets and other artifacts, which he sells to make a living. One night they see a bright light and their hut is shaken by a huge tremor. The next morning, when the man goes out to investigate he finds near his daughter's grave a large egg-shaped object. It begins to crack open and as he watches, a baby crawls from it and begins to grow rapidly until it assumes the form of his dead child. The man and his wife raise the girl as their daughter, Kaya, and discover that the egg-shaped object from which she emerged is pure gold, so they become rich enough to move into a large house. Kaya swiftly grows into a young woman (Yasuko Sawaguchi) whose beauty attracts high-born suitors. But she has brought with her a small crystal ball that eventually reveals her secret: She is from the moon, the sole survivor when the ship that was carrying her crashed. To ward off her suitors, she proposes impossible tasks to win her hand. And then the ball reveals that at the next full moon, a ship will arrive to carry her home. The entire realm has fallen in love with Kaya, and on the night of the full moon, troops are stationed about the house to shoot down any arriving ships. Up to this point, Kon Ichikawa's Princess From the Moon has been a charmingly magical fantasy film, a smart adaptation of an ancient Japanese folktale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, with beautiful sets by Shinobu Muraki, costumes by Emi Wada, and color cinematography by Setsuo Kobayashi. But suddenly Ichikawa imposes on the setting a spaceship out of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), and Kaya is drawn up into it in flowing robes and accompanied by what appear to be glowing cherubs, an image that recalls Renaissance paintings of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, like this one by Rubens:

It's a startling shift in tone and technique, to say the least, especially when compounded by the insertion of a pop song, "Stay With Me," by Peter Cetera behind the end credits. Critics, too, were jarred by the overlaying of a sci-fi trope on a traditional tale, but audiences seemed to like it. A somewhat more traditional version of the story, The Tale of the Princess Kagya (Isao Takahata), was produced by Studio Ghibli in 2013 and was nominated for the animated feature Oscar.

It's a startling shift in tone and technique, to say the least, especially when compounded by the insertion of a pop song, "Stay With Me," by Peter Cetera behind the end credits. Critics, too, were jarred by the overlaying of a sci-fi trope on a traditional tale, but audiences seemed to like it. A somewhat more traditional version of the story, The Tale of the Princess Kagya (Isao Takahata), was produced by Studio Ghibli in 2013 and was nominated for the animated feature Oscar.

Saturday, May 13, 2017

Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950)

It's fun sometimes to go back and read the reviews Bosley Crowther wrote for the New York Times, panning films that are now regarded as classics. Crowther, if you've forgotten, was the lead film critic for the Times for 27 years, until he panned Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) and persisted in attacking the film in follow-up articles until the Times nudged him into retirement. My generation grew up thinking of Crowther as the classic fuddy-duddy. Some of the harsh moralizing that marked his Bonnie and Clyde diatribe was present throughout his career, as in, for example, his comments in his review of Jules Dassin's Night and the City, which he called "a pointless, trashy yarn," a "a turgid pictorial grotesque," "a melange of maggoty episodes," and a "cruel, repulsive picture of human brutishness." It almost makes you want to run right out and see it, doesn't it? But there's a part of me that thinks the old foof was onto something: Night and the City is just a little too dark to be credible, and some elements of it -- such as Richard Widmark's over-the-top performance and the expressionistic camera angles of cinematographer Mutz Greenbaum (billed as Max Greene) -- verge on film noir self-parody. Still, there's a great energy in Night and the City, which often reminds me of Dickens's forays into the underworld -- the titular city is London -- especially when it comes to character names. The chief villain (Francis L. Sullivan, imitating Sydney Greenstreet) is a Mr. Nosseross -- his given name is Philip, not Rye -- and there's a minor character with the über-Dickensian name of Fergus Chilk. Widmark plays Harry Fabian, whose life is a continuous hustle, trying to gather enough money to finance his various get-rich-quick schemes. His long-suffering girlfriend, Mary Bristol (Gene Tierney, in a smaller role than her billing suggests), is a singer in a clip joint run by the Nosserosses -- Philip and his wife, Helen (Googie Withers). Eventually, Harry overreaches by trying to loosen the hold on the pro wrestling exhibition racket in London held by Kristo (Herbert Lom), whose star wrestler is known as the Strangler (Mike Mazurki). Harry cons an honest old Greek wrestler named Gregorius (Stanislaus Zbyszko) into staging a bout between Gregorius's protégé, Nikolas of Athens (Ken Richmond) and the Strangler, but everything goes to hell when Nosseross withdraws his promised financial support. There is a great wrestling scene in which Gregorius himself takes on the Strangler, who has broken Nikolas's wrist. Gregorius wins, but dies of a heart attack afterward, one of the many deaths the movie accumulates. The film makes great atmospheric use of its London setting, which was necessitated because Dassin was about to be blacklisted in Hollywood -- it's to the credit of 20th Century Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck that he warned Dassin of this and, when Dassin decided he would seek work in Europe, allowed him to make the film in London.

Friday, May 12, 2017

Manchester by the Sea (Kenneth Lonergan, 2016)

Sometimes, to appreciate how good a film is you have to imagine how bad it could have been. The conventional way of telling a story is beginning-middle-end, cause-effect-remedy, disease-diagnosis-cure. But if Kenneth Lonergan had taken that strict linear approach in crafting Manchester by the Sea, we would have been deprived of the element of discovery that makes it such a powerful film. To put it this way, Lonergan could have opened with the calamitous event that so blights the life of Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck), and then shown the breakup with his wife, Randi (Michelle Williams); his efforts to lose himself in menial work as a handyman/custodian in Boston; the death of his brother, Joe (Kyle Chandler), and Lee's return to Manchester; the discovery that Joe has made him guardian of Joe's son, Patrick (Lucas Hedges), and the subsequent attempts to arrange his life around that fact. But by postponing the revelation of the terrible event in Lee's life, placing it in a flashback, Lonergan makes it what it has to be: the very center of the film. We want to know what is troubling Lee, why he's so blocked emotionally, and Lonergan makes us wait for the answer, to speculate what it might be. When the revelation comes that he accidentally killed his small children, it probably fulfills what many of us had guessed it might be, so it doesn't come as a brutal surprise but as an elucidation. To put it at the start of the film, including Lee's aborted attempt at suicide, would have turned the film into a sentimental slog toward redemption. But by first showing us the ways in which Lee has responded by hiding away or lashing out at comforters or the curious -- by putting the middle before the beginning, the effect before the cause -- Lonergan focuses on Lee's continuing everyday pain, not on the enormity of what caused it. And then there's the ending: poignant, inconclusive, but at least somewhat hopeful. A conventional ending that provided balm for the pain, a cure for the disease, would have been phony. We may want the film to end with Lee finding some consolation like that of new fatherhood with Patrick, a rapprochement with Randi, even some kind of successful therapy or -- like Elise (Gretchen Mol), Joe's druggie ex-wife and Patrick's strayed mother -- submission into religious faith, but we would be satisfying our desire for a tidy narrative, not Lee's deep needs. Lonergan handles the traditional religious "cure" brilliantly, showing Patrick's discomfort at the evangelical piety of Elise and her new husband, Jeffrey (Matthew Broderick), and his complaint to Lee that Jeffrey is "Christian." Lee reminds him that they're Christians too -- "Catholics are Christians" -- ironically widening the gulf between Patrick and his mother and her husband. Lee's Catholicism is steeped in guilt, an emotion he knows too well and cannot imagine a life without. The strength of a film like Manchester by the Sea lies in its acknowledgment that life is too shaggy, bristly, and spiky to be neatly wrapped up with cures and fixes for whatever ails it.

Thursday, May 11, 2017

Sylvia Scarlett (George Cukor, 1935)

|

| Edmund Gwenn, Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Natalie Paley, and Brian Aherne in Sylvia Scarlett |

Jimmy Monkley: Cary Grant

Michael Fane: Brian Aherne

Henry Scarlett: Edmund Gwenn

Maudie Tilt: Dennie Moore

Lily Levetsky: Natalie Paley

Director: George Cukor

Screenplay: Gladys Unger, John Collier, Mortimer Offner

Based on a novel by Compton MacKenzie

Cinematography: Joseph H. August

Art direction: Van Nest Polglase, Sturges Carne

Film editing: Jane Loring

Music: Roy Webb

Bear with me while I try to remember the plot of Sylvia Scarlett because I'm not entirely sure that I didn't fall asleep and dream it: When the wife of an Englishman living in France dies, he decides to return to England with his daughter. But because he is suspected of having embezzled money from the company for which he is an accountant, he and his daughter decide that she will disguise herself as a boy because the authorities will be looking for a man traveling with a girl. So on the boat crossing the Channel, they meet a cheerful Cockney con-man, to whom the other Englishman confesses that he's smuggling a bolt of fine lace through customs. But when they arrive in England, the Cockney points them out to the officials and the Englishman and his daughter-disguised-as-a-boy are detained and fined and the lace is confiscated. Then on the train to London, they coincidentally find themselves in the same compartment as the Cockney, who not only repays the fine but even gives the Englishman a little extra money, while also revealing that he's a smuggler with diamonds concealed in the heel of his shoe, and that he turned them in to divert attention from himself. All is square, except that now the Cockney proposes that they team up and run a few cons together. They're not very good at it, so when the Cockney reads an article saying that a rich couple are taking an extended holiday out of the country, he decides that they should rob the deserted house. The plan is thwarted by the maid the couple has left behind, so they persuade her to go on the road with them as traveling entertainers. They hire a wagon and go to Cornwall and give a show that attracts the attention of a rich young artist and his Russian girlfriend. The artist tells the son/daughter that he wants to paint him/her, but he/she swipes a dress and a hat that were left behind on the beach by a woman who has gone swimming and shows up at his studio as a woman, but the Russian girlfriend is outraged to find her there. Meanwhile, the Englishman has taken to drink and fallen in love with the maid and one night wanders out drunkenly in the fog and falls to his death from a cliff. After his funeral, the daughter and the Cockney return to their wagon (the maid has somehow disappeared for good), but they hear a cry for help from the Russian, who has apparently attempted suicide because the artist doesn't love her anymore, so the daughter plunges into the ocean and rescues her, returning her to the artist. Then the Cockney and the Russian decide to run away together, so the daughter and the artist pursue them, winding up on a train and somehow realizing that they're in love with each other. Now, to the point: Why in hell did anyone ever think this made enough sense to film? Or that the completed film would please critics and attract audiences? (It didn't.) And why is this not on the usual lists of the worst films ever made? Because the truth is, it's not unwatchable, and sometimes, if you're in the mood for the utterly bizarre, it's sort of fun to watch, mainly because the Cockney is played by Cary Grant and the son-daughter by Katharine Hepburn, in their first on-screen teaming.* And perhaps because Edmund Gwenn as the Englishman is as charming as ever. And also perhaps because George Cukor is one of the few directors of the period who could leaven this lump of Edwardian nonsense: It's based on a novel by Compton MacKenzie, a now-forgotten writer with a taste for whimsy and a tolerance for sexual ambiguity. The screenplay was mostly written by John Collier, another writer with a decidedly eccentric view of the world, with the help of Gladys Unger and Mortimer Offner. Naturally, the Production Code weighs heavily on the ambiguous sexuality of the film, though we are never really quite sure whether the artist played by Brian Aherne is more attracted to Sylvia than to Sylvester. (Hepburn is quite beautiful as either.) But mostly the film gives us a chance to see Grant before Archibald Leach, the product of a troubled working-class family, became "Cary Grant," the embodiment of sophistication: There's a darkly threatening sexuality to his character, Jimmy Monkley, that's compelling and makes us wonder why Hepburn's Sylvia should prefer Aherne's much softer Michael Fane. Sylvia Scarlett has a cult following today that it doesn't entirely deserve, but it remains a fascinatingly mad mess.

*They went on to make two more films for George Cukor, Holiday (1938) and The Philadelphia Story (1940), but their most memorable work together was for Howard Hawks on Bringing Up Baby (1938).

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

The 39 Steps (Alfred Hitchcock, 1935)

The 39 Steps, Alfred Hitchcock's first great film, contains an object lesson in how to end a movie, a topic I raised in passing when I blogged about Steven Spielberg's Bridge of Spies (2016) a week or so ago. Rather than tie everything up in a neat package with a flowery bow as Spielberg tries to do in his film, Hitchcock simply ends after the confession and death of Mr. Memory (Wylie Watson) -- shot with beautiful irony against a background of high-kicking chorus girls -- in a closeup of Hannay (Robert Donat) and Pamela (Madeleine Carroll) holding hands, the handcuffs still dangling from Hannay's wrist. Nothing more needs to be said or shown, although a scene was apparently shot in which it's made more explicit that Hannay and Pamela are now a couple. Who needs it? The 39 Steps established Hitchcock as the master of the romantic thriller. There are those who regret that he never moved very far out of that genre, and who wish that he could have devoted himself to more highly serious material than John Buchan, who wrote the novel on which the film is based -- Dostoevsky, perhaps. But that's the kind of aesthetic puritanism that leads directors astray into high-minded dullness. We should be grateful that Hitchcock never succumbed to it, and that he continued to devote himself to an almost unique economy of narrative and to developing his skill at creating ways to distract the viewer from noticing a story's holes. How, exactly, does Hannay get from the Forth Bridge to the Scottish Highlands? By the same sleight-of-hand that gets Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) from New York to Chicago to Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest (1959), of course. And again, who cares? It's also the first of his films to rely on star power, the charisma and charm of the young Donat and the first of the director's "icy blonds," Carroll, who was never more appealing than in this film. At the same time, he also acknowledges the necessity of supporting players who can give the film texture and depth. I'm speaking here particularly of such narrative filigree as the crofter (John Laurie) and his wife (Peggy Ashcroft), the milkman (Frederick Piper) who lends Hannay his white coat and cap, the traveling salesmen (Gus McNaughton and Jerry Verno) on the train, and the professor's wife (Helen Haye) who is so unperturbed at seeing her husband (Godfrey Tearle) pointing a gun at Hannay. These are mostly the creations of Hitchcock and his screenwriter, Charles Bennett, and not John Buchan. Who reads Buchan anymore? Who doesn't want to watch Hitchcock's film again?

Tuesday, May 9, 2017

Lady in the Lake (Robert Montgomery, 1947)

I am not a camera. If you ever want to see what movies could be like if no one had discovered montage, crosscutting, expressive camera angles, and other techniques that make them so involving, just watch Robert Montgomery's debut* as a director, Lady in the Lake. The gimmick (and it's little more than that) of this film based on a novel by Raymond Chandler is that the audience sees everything that happens through the eyes of Philip Marlowe, thereby becoming the detective. Montgomery plays Marlowe, but except for occasional reflections in mirrors, he's on screen only in set-up segments that clue the audience into the gimmick. Naturally, the film has to cheat, as when there's a cut when Marlowe travels between one location and another, but the major problem is that what the camera mostly sees is people standing there talking to it, a point of view that soon gets tiresome. Some of the cast rise to the demand of the long takes and extended dialogue without the usual shot/reverse shot cuts. Tom Tully, for example, makes his police captain threatening and then undercuts the threat when Marlowe witnesses him on the telephone with his young daughter, promising to come home early on Christmas Eve and play "Santy Claus." (The choice to set the film at Christmas -- it isn't in the book -- is perhaps meant to create a kind of ironic dissonance. If so, it doesn't work.) Jayne Meadows is fun as the apparently scatterbrained landlady who later turns out to be a somewhat more menacing figure. But the female lead, Audrey Totter, as the Chandlerian femme fatale, is an inexpressive actress, resorting to a lot of eye-popping to express emotion. She looks like her face has been shot full of Botox, years before it was invented. Montgomery, who is heard more than he's seen, is miscast as Marlowe, his patrician handsomeness much at odds with the hard-boiled Marlowe made familiar to us by Humphrey Bogart, Dick Powell, and others. There are some good moments, such as an effective sequence in which the camera is behind the wheel in the car Marlowe is driving, but too often the gimmick makes us pay attention to itself rather than to the story being told.

*Official debut, that is. Montgomery had done some uncredited work behind the camera for John Ford on They Were Expendable (1945).

*Official debut, that is. Montgomery had done some uncredited work behind the camera for John Ford on They Were Expendable (1945).

Monday, May 8, 2017

Everybody Wants Some!! (Richard Linklater, 2016)

Watching Richard Linklater's Everybody Wants Some!! a day or two after Yasujiro Ozu's Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? reminded me that one of the essential characteristics of a great director is a compassionate interest in human beings. It's not that they are both comedies about college students: They are also both "coming-of-age" films, although Linklater lets us extrapolate the course of his characters' potential maturity (or lack of it), while Ozu lets his characters mature before our eyes. Ozu and Linklater have been called "sociological" filmmakers because their movies tend to be about what happens to their characters in a given cultural context: in the case of Linklater's film a group of young jocks at a Texas college in 1980; in Ozu's, Japanese college students in the early years of the Great Depression. Linklater has acknowledged that Everybody Wants Some!! is a kind of coda to Dazed and Confused (1993), the action of which takes place four years earlier on the last day of high school. The newer film is more narrowly focused than the earlier one, which had a sampling of all types of high schoolers, male and female, from brains to jocks, from bullies to victims. Everybody is centered on a group of horny young men, highly competitive college baseball players, all of whom have dreams of making it as pros. But it's still an ensemble work, with a gallery of good young actors, mostly familiar from TV: Blake Jenner from Glee, Tyler Hoechlin from Teen Wolf, Ryan Guzman from Pretty Little Liars, among others. Linklater forces us to see through the jock stereotypes and find the brains and hearts intentionally hidden behind the bravado and braggadocio of hormones and muscles. He's interested primarily in his characters' intense competitiveness and in their swiftly fading innocence. As in Dazed and Confused, in which the older stoner Wooderson (Matthew McConaughey) exhibited the Peter Pan syndrome, unwilling to leave adolescence behind, in Everybody we meet Willoughby (Wyatt Russell), a 30-year-old who masquerades as a transfer student from San Luis Obispo, trying to prolong the blissful innocence of a life spent smoking dope and playing ball. The adult world rarely intrudes on the film's characters: The coach's prohibition of alcohol and women in the residence houses is quickly ignored. But Linklater neither preaches responsibility nor sentimentalizes immaturity. In the last scene, the freshmen Jake (Jenner) and Plummer (Temple Baker) finally get to their first college class after a weekend of partying and promptly put their heads down to sleep through the history professor's lecture. They're young and have no history, or as Willoughby puts it, they're there "for a good time, not for a long time." As good as it is, Everybody "underperformed" at the box office, perhaps because it looks too much like a routine teen sex comedy for discerning audiences and didn't have enough gross-out humor or marketable stars for the usual audience for that genre.

Sunday, May 7, 2017

Murder, My Sweet (Edward Dmytryk, 1944)

Because it's based on a Raymond Chandler novel, Murder, My Sweet is inevitably subject to comparisons with another Chandler-based film noir, The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946). Which is unfortunate, because Edward Dmytryk was no Hawks, and Dick Powell and Anne Shirley were certainly not Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. But then who is? Murder, My Sweet is good stuff anyway: a steady-moving, entertainingly complicated film noir. And though Dick Powell, the first actor to play Philip Marlowe on screen, doesn't eclipse Bogart's version, he holds his own well alongside other Marlowe incarnations like James Garner, Elliott Gould, and Robert Mitchum. Powell had just turned 40 when Murder, My Sweet was released, and had lost the baby face that made him a star in Busby Berkeley musicals and in comedies like Christmas in July (Preston Sturges, 1940). (It's said that RKO changed the title of the film from that of Chandler's novel, Farewell, My Lovely, because it was afraid that people would think it was a musical.) Powell looks a little slight to take as many sappings as he does in the film -- usually accompanied by the voiceover, "A black pool opened at my feet. I dived in. It had no bottom." But he handles the tough-guy lines in John Paxton's screenplay well, and there are plenty of good ones like "She was a gal who would take a drink, if she had to knock you down to get the bottle." Or: "My throat felt sore, but the fingers feeling it didn't feel anything. They were just a bunch of bananas that looked like fingers." As usual, we don't know who's good or who's bad for a while, but they're almost all pretty bad, especially Claire Trevor as Helen Grayle, whose former identity as Velma Valento, whom Marlowe is initially hired to locate by Moose Malloy (Mike Mazurki), is what ties together all the various plots and subplots about jade necklaces and the like. This was the last film for Anne Shirley, who married the producer of Murder, My Sweet, Adrian Scott, and retired. Scott later became one of the Hollywood Ten who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee and was blacklisted. Dmytryk was also one of the Ten, but after his initial refusal to testify, he changed his mind, and gave the unverifiable testimony that Scott and the others had put pressure on him to insert communist propaganda into his films.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)