A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Emi Wada. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Emi Wada. Show all posts

Sunday, February 9, 2020

Hero (Zhang Yimou, 2002)

Cast: Jet Li, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung, Zhang Ziyi, Chen Daoming, Donnie Yen, Zhongyuan Liu, Tianyong Zheng, Yan Qin, Chang Xiao Yang. Screenplay: Feng Li, Zhang Yimou, Bin Wang. Cinematography: Christopher Doyle. Production design: Tingxiao Huo, Zhenzhou Yi. Film editing: Angie Lam, Vincent Lee. Costume design: Emi Wada. Music: Tan Dun.

Visually, one of the most beautiful films ever made, Hero is a ravishing blend of color, texture, pattern, and movement, with spectacular locations that range from desert to mountain, from forest to lake. If it had as much to please the mind as it does the eye -- and ear, counting Tan Dun's score -- it might have been one of the great films. It's a fable about the emergence of China as a nation under its first emperor, using a Rashomon-like narrative structure in which we get various versions of the story of how a swordsman known as Nameless (Jet Li) vanquished three assassins -- Sky (Donnie Yen), Broken Sword (Tony Leung), and Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung) -- to earn the right to come within ten paces of the king of Qin (Chen Daoming), in other words, to come within killing distance of the ruler. Nameless first tells his story, and then the king responds with his own theory about what really happened. A true version, in which Nameless is revealed as the real assassin, finally emerges. The result is to give us flashbacks to a variety of fight sequences, involving some astonishing wire work in several breathtaking settings, the most memorable of which may be the duel in the yellow leaves of an autumnal forest between Flying Snow and Moon (Zhang Ziyi), Broken Sword's apprentice and rival with Snow for his love. In the end, however, the film seems to have no real point to make other than the need for strong and powerful leadership, which is not exactly a positive statement in these days.

Sunday, June 10, 2018

Ran (Akira Kurosawa, 1985)

|

| Jinpachi Nezu and Mieko Harada in Ran |

Taro Takatora Ichimonji: Akira Terao

Jiro Masatora Ichimonji: Jinpachi Nezu

Saburo Naotora Ichimonji: Daisuke Ryo

Lady Kaede: Mieko Harada

Lady Sué: Yoshiko Miyazaki

Shuri Kurogane: Hisashi Igawa

Kyoami: Pîtâ

Tango Hirayama: Masayuki Yui

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, Hideo Oguni, Masato Ide

Based on a play by William Shakespeare

Cinematography: Asakazu Nakai, Takao Saito, Shoji Ueda

Production design: Shinobu Muraki, Yoshiro Muraki

Film editing: Akira Kurosawa

Music: Toru Takemitsu

Costume design: Emi Wada

Lavish in color and pattern, Ran may be Akira Kurosawa's most pictorial film, to the point that the images and costumes and sets sometimes threaten to overwhelm the human drama at its core. To the extent that this is Kurosawa's second effort at translating a Shakespeare play into medieval Japanese terms, I have to say that I prefer his adaptation of Macbeth, the 1957 Throne of Blood, to this reworking of King Lear. It seems to me that in Ran, Kurosawa stumbles over the analogous figures from Shakespeare in ways that he doesn't in his earlier film. Turning Lear's daughters into Hidetora's sons robs much of the delicacy and painful sadness of the Shakespeare play, especially in the final reunion of Lear and Cordelia. And King Lear is a more complex play than Macbeth, with its intricate subplot involving Gloucester and his sons, and the multiple intrigues of the households of Goneril and Regan. Kurosawa has pared down and fused some of these secondary stories, but he still loses sight at times of his central figure, the Lear analog, Lord Hidetora. Tatsuya Nakadai is unquestionably one of the world's great film actors, but he's too sturdy a figure for the enfeebled Hidetora, and the stylized old-age makeup often hides his features -- except for the great, glaring eyes. There are grand things, however, in the film, including a wonderfully villainous performance by Mieko Harada as the Lady Kaede, and a curiously effective Fool, performed by the androgynous actor-dancer known as Pîtâ.

Sunday, May 14, 2017

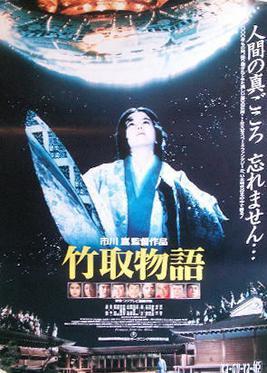

Princess From the Moon (Kon Ichikawa, 1987)

In eighth-century Japan, a man (Toshiro Mifune) and his wife (Ayako Wakao) are mourning the death of their 5-year-old daughter, Kaya. They live beside a forest of bamboo, whose stalks the man cuts and turns into baskets and other artifacts, which he sells to make a living. One night they see a bright light and their hut is shaken by a huge tremor. The next morning, when the man goes out to investigate he finds near his daughter's grave a large egg-shaped object. It begins to crack open and as he watches, a baby crawls from it and begins to grow rapidly until it assumes the form of his dead child. The man and his wife raise the girl as their daughter, Kaya, and discover that the egg-shaped object from which she emerged is pure gold, so they become rich enough to move into a large house. Kaya swiftly grows into a young woman (Yasuko Sawaguchi) whose beauty attracts high-born suitors. But she has brought with her a small crystal ball that eventually reveals her secret: She is from the moon, the sole survivor when the ship that was carrying her crashed. To ward off her suitors, she proposes impossible tasks to win her hand. And then the ball reveals that at the next full moon, a ship will arrive to carry her home. The entire realm has fallen in love with Kaya, and on the night of the full moon, troops are stationed about the house to shoot down any arriving ships. Up to this point, Kon Ichikawa's Princess From the Moon has been a charmingly magical fantasy film, a smart adaptation of an ancient Japanese folktale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, with beautiful sets by Shinobu Muraki, costumes by Emi Wada, and color cinematography by Setsuo Kobayashi. But suddenly Ichikawa imposes on the setting a spaceship out of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), and Kaya is drawn up into it in flowing robes and accompanied by what appear to be glowing cherubs, an image that recalls Renaissance paintings of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, like this one by Rubens:

It's a startling shift in tone and technique, to say the least, especially when compounded by the insertion of a pop song, "Stay With Me," by Peter Cetera behind the end credits. Critics, too, were jarred by the overlaying of a sci-fi trope on a traditional tale, but audiences seemed to like it. A somewhat more traditional version of the story, The Tale of the Princess Kagya (Isao Takahata), was produced by Studio Ghibli in 2013 and was nominated for the animated feature Oscar.

It's a startling shift in tone and technique, to say the least, especially when compounded by the insertion of a pop song, "Stay With Me," by Peter Cetera behind the end credits. Critics, too, were jarred by the overlaying of a sci-fi trope on a traditional tale, but audiences seemed to like it. A somewhat more traditional version of the story, The Tale of the Princess Kagya (Isao Takahata), was produced by Studio Ghibli in 2013 and was nominated for the animated feature Oscar.

Monday, February 15, 2016

House of Flying Daggers (Yimou Zhang, 2004)

From the kaleidoscopic color of the Peony Palace at the beginning of the film through the final duel seen through the scrim of a blizzard, House of Flying Daggers is visually extraordinary, fully deserving of its Academy Award nomination for Xiaoding Zhao's cinematography. It tends, however, to be a collection of brilliant set pieces, including a spectacular battle in a bamboo forest, held together by what could be a conventional love triangle -- if only the stories of the three members of the triangle, Jin (Takeshi Kaneshiro), Leo (Andy Lau), and Mei (Zhang Ziyi ), weren't so extraordinarily complicated. In the story by director Zhang Yimou , Feng Li, and Bin Wang, it is 859 C.E., and the police are trying to root out the House of Flying Daggers, a group of Robin Hood-style rebels against the government of the Tang Dynasty. Police captain Leo and his subordinate, Jin, hear that an agent of the Flying Daggers is working incognito at the Peony Palace, a brothel, so they arrest Mei, a blind dancer. But neither Mei nor Leo is exactly who they appear to be, which is unfortunate for Jin, who falls in love with Mei, with fatal consequences. In the end, it's best just to sit back and admire the performances of the three actors, especially Zhang Ziyi , who is truly astonishing in both the action sequences and the dramatic scenes. In addition to Zhao's cinematography, the visual impact of the film depends largely on the work of production designer, Tingxiao Huo, art director Zhong Han, and costume designer Emi Wada. Most of the exterior scenes, with the exception of the bamboo forest, were filmed on location in the Carpathian Mountains of Ukraine.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)