Vive l’Amour (Tsai Ming-liang, 1994)

Cast: Chen Chao-jung, Lee Kang-sheng, Yang Kue-Mei. Screenplay: Tsai Ming-liang, Tsai Yi-chun, Yang Pi-ying. Cinematography: Liao Pen-Jung, Lin Ming-Kuo. Production design: Lee Pao-Lin. Film editing: Sung Shia-cheng.

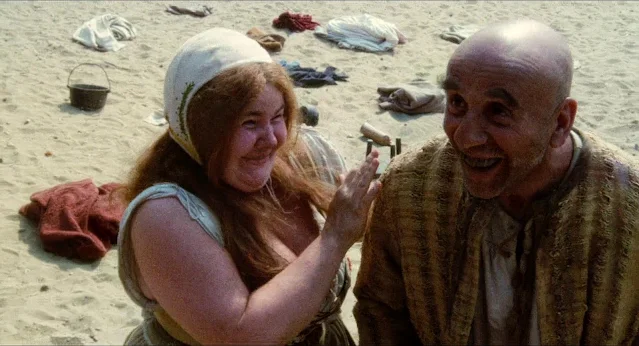

Vive l’Amour, the ironic title of Tsai Ming-liang’s film, brings to mind another French phrase: comédie larmoyante. And not just because it ends with a very long close-up of the character May Lin (Yang Kue-Mei) sobbing bitterly, but because the film is its own kind of tearful comedy, one with roots in the genre of farce, in which characters occupy a common space but somehow avoid making connection with one another. It’s a story about existential loneliness. Ah-jung (Chen Chao-jung) is making his rounds in the gloomy job of funerary urn salesman when he finds a key left in the lock of a vacant luxury apartment. He sneaks in at night planning to commit suicide, but only makes a half-hearted attempt at cutting his wrist with a Swiss army knife and bandages himself up. Then he realizes that he’s not alone in the large apartment when he hears a couple having sex in another room. They are May Lin, the real estate agent supposed to be showing the apartment to clients, and Hsiao-kang (Lee Kang-sheng), who have picked each other up in a restaurant. Hsiao-kang, who illegally sells women’s dresses on the street, steals her key to the apartment and moves in. Eventually, Ah-jung and Hsiao-kang encounter each other and become friends. But their friendship is tested when May Lin and Hsiao-kang return to the apartment, and Ah-jung, hearing them enter, hides under the bed. As the couple have sex, Ah-jung masturbates below them. After May Lin leaves, Ah-jung gets in bed with the sleeping Hsiao-kang and stares at him longingly, then kisses him. May LIn, having discovered that her car won’t start, sets out to walk home but winds up weeping on a park bench. The story of the three is intercut with glimpses of their lonely lives: May Lin waiting patiently for clients that don’t show, Ah-jung distributing leaflets advertising his urns, Hsiao-kang trying on one of the dresses he peddles. There’s no music score and very little expository dialogue, but the sound track is alive, from the noise of love-making Ah-jung hears from another room to the pock-pock-pock of May Lin’s heels as she sets out on her long walk homeward. We don’t know why May Lin weeps, or what drives Ah-jung to consider suicide, but by showing the texture of their isolated lives, Tsai makes us intuit the causes.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)