|

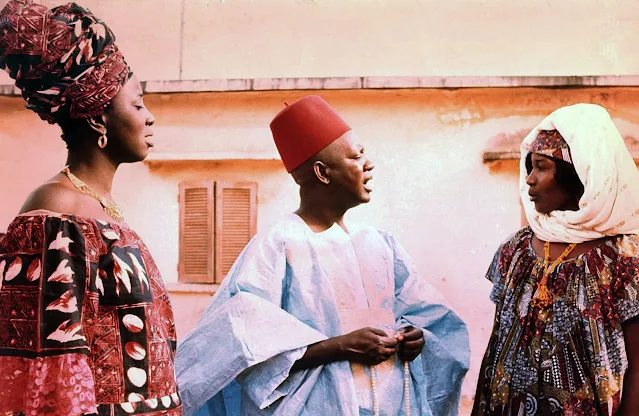

| Ynousse N'Diaye, Makhouredia Gueye, and Isseu Niang |

Cast: Makhouredia Gueye, Ynousse N'Diave, Isseu Niang, Mustapha Ture, Farba Sarr, Serigne Diayes, Thérèse Bas, Mouss Diaf, Christof Colomb. Screenplay: Ousmane Sembene. Cinematography: Paul Soulignac. Film editing: Gilbert Kikoïne, Max Saldinger.

When we first see Ibrahim Dieng (Makhouredia Gueye), he is having his head shaved and his nose cleaned. Then he strolls through the streets of Dakar, immaculate head held high, the very image of smug prosperity. He is anything but prosperous, of course: He is stone broke, having been unemployed for a very long time, supporting himself, his two wives, and seven children with a combination of handouts and loans, sustained mainly by his pride and a Micawberish sense that something will turn up. That something turns up in the form of a money order from his nephew, a street sweeper in Paris, and it will be the undoing of Ibrahim. Most of the money his nephew sent is not his: Part of it is to go into the nephew's savings, part to his mother, Ibrahim's sister (Thérèse Bas), who is a formidable force herself. The little left over goes to Ibrahim, and the thought of it elicits a brief period of delight -- one of the wives even makes up a song about the money order. But when word of it gets about, Ibrahim is immediately set upon by creditors and handout seekers. Mandabi (which means "money order") is a tragicomic film about postcolonial Africa, its people strangled by governmental corruption. Ibrahim is caught in a Catch-22: He can't cash the money order without an identity card. He can't get an identity card without a birth certificate. He can't get a birth certificate without some form of identification. The bureaucracy that frustrates him is both Dickensian and Kafkaesque. Ousmane Sembene tells Ibrahim's story with sympathy, but also with a smart distancing from the character, whose faults he makes all too clear. The only problem I had with the film is that it ends with a didactic speech by a character delivering the message: People should work to end the corruption that results in such misery. But Mandabi wasn't made for me, but for people like the ones it portrays. It was the first feature made in Wolof, the indigenous language of Senegal, which Sembene chose over French, the official language imposed by colonialism. "Message movies" may be tiresome to us Westerners, but they were an important tool for filmmakers like Sembene.