A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, December 31, 2019

Fog Over Frisco (William Dieterle, 1934)

Fog Over Frisco (William Dieterle, 1934)

Cast: Bette Davis, Donald Woods, Margaret Lindsay, Lyle Talbot, Hugh Herbert, Arthur Byron, Robert Barrat, Henry O'Neill, Irving Pichel, Douglas Dumbrille, Alan Hale, Gordon Westcott. Screenplay: Robert N. Lee, Eugene Solow, based on a story by George Dyer. Cinematography: Tony Gaudio. Art direction: Jack Okey. Film editing: Harold McLernon. Music: Bernhard Kaun.

San Franciscans don't call it Frisco anymore but they do call the fog Karl. Not that fog has a lot to do with the story of Fog Over Frisco, which is mostly a fast-paced murder mystery involving a socially prominent family and some stolen securities. Although Bette Davis is nominally the star, she's the murder victim and disappears from the film halfway through. Her prominent billing probably has to do with the realization at Warner Bros. that she was becoming a big star: This is also the year of Of Human Bondage, the John Cromwell film that Davis made on loanout to RKO. Although Margaret Lindsay, who plays Davis's stepsister, has the larger part, and the cast is full of watchable character actors like Hugh Herbert, Alan Hale, and (in a small part) William Demarest, Davis still shines -- so much so that we miss her in the latter half of the movie. Another attraction to the film are the scenes shot on location in San Francisco, notably lacking any shots of the Golden Gate Bridge, which was under construction.

Monday, December 30, 2019

Marriage Story (Noah Baumbach, 2019)

Marriage Story (Noah Baumbach, 2019)

Cast: Scarlett Johansson, Adam Driver, Laura Dern, Ray Liotta, Alan Alda, Azhy Robertson, Wallace Shawn, Julie Hagerty, Merritt Wever, Martha Kelly. Screenplay: Noah Baumbach. Cinematography: Robbie Ryan. Production design: Jade Healy. Film editing: Jennifer Lame. Music: Randy Newman.

The enthralling performances of Scarlett Johansson and Adam Driver give Marriage Story its solid substance, and Noah Baumbach's direction of them provides its estimable style. He lets Johansson deliver Nicole's indictment to her lawyer of Charlie's faults in a single-take monologue, and has the confrontation of Nicole and Charlie in his L.A. apartment build in a slow crescendo that ends with Charlie slamming his fist into the wall, then collapsing on the floor to be comforted by her. But my favorite scene is probably the visit of the court-appointed examiner to Charlie's apartment. She's drab and diminutive, towered over by the hulking Driver, but we sense how much power she holds over Charlie -- as does he, constantly putting his foot wrong no matter how he tries not to. Driver is simply wonderful in a scene that concludes with Charlie cutting himself in an attempt to defuse Henry's embarrassing revelation that he plays a trick with a knife. The trick goes wrong and Charlie, bleeding profusely, assures the examiner that it's really nothing, ushers her out of the door, then rushes to the kitchen to try to stanch the flow of blood, frantically applying band-aids and unreeling a lot of paper towels before falling to the floor, almost catatonic with chagrin. It's a hugely accomplished movie, with some faults, I think. Wallace Shawn's vain old actor, blathering on about his Tony award and his past accomplishments is a caricature, as is Julie Hagerty's dithery turn as Nicole's mother. The lawyers are too easily slotted into their roles as villains, spoiling Nicole and Charlie's plans for a friendly divorce. Only the skill of Laura Dern, Ray Liotta, and Alan Alda keeps their characters from descending to the level of cliché, though Dern's Nora echoes her role as Renata in Big Little Lies a bit more than I'd like. But the intelligence of the central performances outshines all of the film's missteps.

Sunday, December 29, 2019

Waterloo Bridge (James Whale, 1931)

Waterloo Bridge (James Whale, 1931)

Cast: Mae Clarke, Douglass Montgomery, Doris Lloyd, Frederick Kerr, Enid Bennett, Bette Davis, Ethel Griffies, Rita Carlyle, Ruth Handforth. Screenplay: Benn W. Levy, Tom Reed, based on a play by Robert E. Sherwood. Cinematography: Arthur Edeson. Art direction: Charles D. Hall. Film editing: Clarence Kolster, James Whale. Music: Val Burton.

If I had to name a favorite underappreciated director, I think it might be James Whale, best known for Frankenstein (1931) and its even better sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935) but also for the first (and best) sound version of Show Boat (1936) and for the semi-spoofy The Old Dark House (1932). Whale had a gift for irony and for spiking things with a bit of acid wit -- something that becomes apparent when you compare his version of Waterloo Bridge with Mervyn LeRoy's somewhat mushier 1940 film. MGM tried to suppress Whale's film when it got the rights to make its own version of the Robert E. Sherwood play, but it didn't have to work hard: The Production Code had made the earlier version, which is more explicit about the fact that Mae Clarke's Myra is a streetwalker, unavailable for exhibition when it went into effect in 1934. As an actress, Clarke wasn't a patch on Vivien Leigh, who played Myra in the later film, but she doesn't really have to be; Whale's direction keeps the story moving and surrounds her with some strong performances, including Doris Lloyd as her tough-girl friend Kitty and Ethel Griffies as the landlady. I was puzzled when I saw her leading man, billed as Kent Douglass. I knew I'd seen him before, and it wasn't until I checked that I recognized him as the Douglass Montgomery who played Laurie in the 1933 Little Women. He's suitably callow in both parts, which acted to his detriment in establishing a career, though I prefer him to the ever-pretty, ever-vacant Robert Taylor, who played the same role in the 1940 Waterloo Bridge. Billed sixth in the cast, after Frederick Kerr and Enid Bennett, is Bette Davis, who plays Montgomery's sister, Janet -- a space-filler of a role. If Davis had been cast as Myra -- which she devoutly wanted to be -- this version of the story might not have been lost to sight for so long. It was stored in the vaults at Universal, where it was discovered in 1975 but not released until the 1990s.

Saturday, December 28, 2019

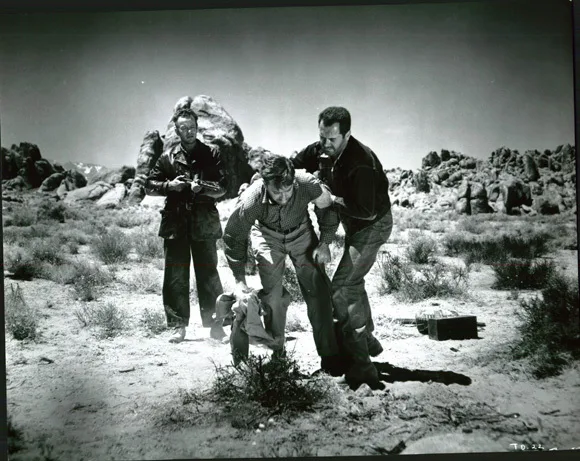

The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953)

The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953)

Cast: Edmond O'Brien, Frank Lovejoy, William Talman, José Torvay, Sam Hayes, Wendell Niles, Jean Del Val, Clark Howat, Natividad Vacío. Screenplay: Collier Young, Ida Lupino, Robert L. Joseph, Daniel Mainwaring. Cinematography: Nicholas Musuraca. Art direction: Albert S. D'Agostino, Walter E. Keller. Film editing: Douglas Stewart. Music: Leith Stevens.

The thing I admire most about The Hitch-Hiker is its economy. It doesn't waste time giving us, for example, the backstory of Roy Collins and Gilbert Bowen, the two guys played by Edmond O'Brien and Frank Lovejoy. Lesser films would have given us scenes in which they bid farewell to their wives and children, trying to establish them as good guys in the hands of a psychopath -- we catch on to that fast enough without sentimental ties back home. Ida Lupino doesn't need to mess around with unnecessary sympathy for them. In fact, we're aware that they're not entirely paragons of virtue: They bicker, for example, about where they're going to spend their little time away from their wives, and there's a suggestion that they're glad to get away from home and family -- it looks like they want a little more action than just fishing. Later, after they've been trapped by Emmett Myers (a wonderfully scary performance by William Talman that makes me regret he got forever stuck as Hamilton Burger, the loser D.A. on the Perry Mason TV series), they quarrel about how they might escape from his clutches -- at one point Bowen even slugs Collins, who is on the verge of hysterics. There are some flaws: It's never really clear why Myers doesn't just shoot at least one of them -- he doesn't really need both to complete his journey to Santa Rosalía. And I do think the film falls a little flat at the end when Myers is so easily captured, but not enough to mar the gritty whole of the movie. Lupino and cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca use the desert landscape to great effect: It provides both isolation and exposure. The Hitch-Hiker deserves its reputation well beyond its historical distinction as a film noir with an all-male cast directed by a (gasp!) woman.

Friday, December 27, 2019

Some Came Running (Vincente Minnelli, 1958)

Some Came Running (Vincente Minnelli, 1958)

Cast: Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Shirley MacLaine, Martha Hyer, Arthur Kennedy, Nancy Gates, Leora Dana, Betty Lou Keim, Larry Gates. Screenplay: John Patrick, Arthur Sheekman, based on a novel by James Jones. Cinematography: William H. Daniels. Art direction: William A. Horning, Urie McCleary. Film editing: Adrienne Fazan. Music: Elmer Bernstein.

Like Douglas Sirk, Vincente Minnelli had a special touch with the movie melodrama, taking its often objectively silly elements seriously enough that you can actually believe in them. The James Jones novel on which the screenplay for Some Came Running was based is one of those semi-autobiographical books that writers seem to need to get out of their systems, but adapting it meant challenging the Production Code strictures, particularly on sex, at almost every turn. So the characters in the film are only as believable as the actors can make them. There's a lot of shorthand in the film about the relationships between Dave Hirsh (Frank Sinatra) and the two women in his life, the "schoolteacher" Gwen French (Martha Hyer) and the "floozie" Ginnie Moorehead (Shirley MacLaine). It's not immediately clear why Dave falls in love so swiftly with Gwen, who seems to want to mentor him as a writer more than she does to sleep with him, or why he stays connected with the illiterate and rattle-brained Ginnie, to the extent of marrying her on the rebound from Gwen. Fortunately, all three actors are adept at pulling characters out of the script, where they don't seem to have been fully written. Dean Martin was just beginning to show that he could act -- Howard Hawks would complete the process the following year with Rio Bravo -- and Minnelli helped give his career a boost by casting him as the alcoholic gambler Bama Dillert. And Arthur Kennedy completes the ensemble as Dave's go-getter older brother, Frank. Minnelli makes the most of these colorful performers, to the extent that MacLaine, Kennedy, and Hyer all received Oscar nominations. But he's also adept, as he would show in 1960 with Home From the Hill, at taking a real small town location and bringing it to full life, especially in the climactic scene that takes place in the carnival celebrating the town's centennial. The location gives the film a substance and reality that the script never quite supplies.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)