|

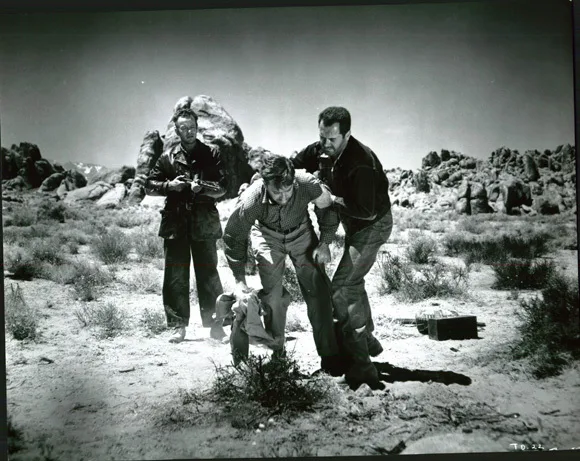

| Ida Lupino and Ronald Colman in The Light That Failed |

Cast: Ronald Colman, Walter Huston, Muriel Angelus, Ida Lupino, Dudley Digges, Ernest Cossart, Ferike Boros, Pedro de Cordoba, Colin Tapley, Ronald Sinclair, Sarita Wooton, Halliwell Hobbes. Screenplay: Robert Carson, based on a novel by Rudyard Kipling. Cinematography: Theodor Sparkuhl. Art direction: Hans Dreier, Robert Odell. Film editing: Thomas Scott. Music: Victor Young.

Screenwriter Robert Carson and director William A. Wellman do an efficient job of condensing Rudyard Kipling's 1891 novel The Light That Failed, leaving in not only the source's colonialism and resentment at the commercialization of art but also the hints of a queer subtext. For like most writers who choose war and adventure as their subject, Kipling tended to focus more on male bonding than on heterosexual relationships. Dick Heldar (Ronald Colman) is an artist who shares lodgings with a war correspondent named Torpenow (Walter Huston); they met in Sudan, where Heldar was wounded while saving Torpenow's life. His paintings based on his wartime sketches earn Heldar some wealth and celebrity, but he wants to be a "real" artist. He meets a childhood friend, Maisie (Muriel Angelus), who is also an artist, but whose career had not taken off as Heldar's had done. They have a platonic relationship that Heldar is interested in developing into something more, but she goes back to her studies in Paris. One night, Torpenow finds a streetwalker named Bessie Broke (Ida Lupino) who collapsed from hunger on the street and brings her back to the flat. Bessie makes a play for Torpenow, offering to keep house for him, but Heldar nixes it, angering her. Still, she agrees to model for Heldar, who finds her face interesting. He paints a portrait that blends her expression with Maisie's face, and is convinced that it will make his reputation as a serious artist, but just as he completes it, he goes blind, a consequence of the wound he received in Sudan. Despite some strain at stuffing all of this exposition and its fateful consequences, along with somewhat eccentric character relationships, into a 99-minute movie, The Light That Failed is a solid melodrama and an early triumph for Lupino, who makes the most of a role she eagerly sought. Colman wanted Vivien Leigh to play Bessie and didn't get along at all with Wellman, so he reportedly displayed some pique during the filming.