|

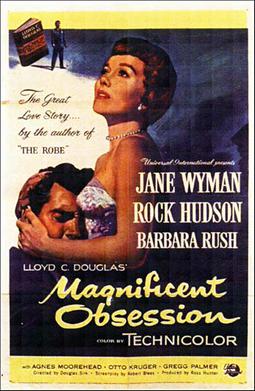

| Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in All That Heaven Allows |

Cary Scott: Jane Wyman

Ron Kirby: Rock Hudson

Sara Warren: Agnes Moorehead

Kay Scott: Gloria Talbott

Ned Scott: William Reynolds

Harvey: Conrad Nagel

Mick Anderson: Charles Drake

Alida Anderson: Virginia Grey

Mona Plash: Jacqueline deWit

Howard Hoffer: Donald Curtis

Mary Ann: Merry Anders

Director: Douglas Sirk

Screenplay: Peg Fenwick

Based on a story by Edna L. Lee

and Harry Lee

Cinematography: Russell Metty

Art direction: Alexander Golitzen, Eric Orbom

Music: Frank Skinner

Costume design: Bill Thomas

Pauline Kael called

All That Heaven Allows "trashy," and others have called it "campy," but the ongoing reevaluation of the work of its director, Douglas Sirk, has delivered a new respect for the film, leading to, among other things, its selection in 1995 for inclusion in the Library of Congress's

National Film Registry. Some would still call it a triumph of form over content, because no one today seriously questions Sirk's brilliant exploitation of the technical resources available to him, specifically his unusually expressive work, in collaboration with cinematographer Russell Metty, in Technicolor, a proprietary medium whose proprietors had rigidly fixed ideas about what could be done with it. Sirk called on Metty for, among other things, more shadows and more use of reflections than were conventional in Technicolor. See, for example, the near-silhouetted figures of Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in the still above, with its subtle backlighting. And notice how the television set that's an unwelcome gift to Wyman's Cary Scott from her children is used in the scenes in which it appears: It's never turned on, but instead its blank screen reflects Cary's face, almost as if the set is a cage in which she's trapped. In another scene, it reflects the flames in the fireplace, becoming a little bit of hell. But that symbolic use of the TV set also suggests why we ought to take

All That Heaven Allows more seriously for its content, as filmmakers like Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Todd Haynes have done by echoing it in their films. Because

ATHA is the epitome of the "woman's picture" as ironic commentary on what women experienced in the 1950s. For all her masculine name, Cary undergoes a constant reminder of her vulnerability as a woman: She is nearly raped by the drunken Howard Hoffer. At or near 40 (Wyman was 38), she is thought by her children to be beyond remarrying for love or even sex: Hence their tolerance of a proposal from the asexual or possibly closeted Harvey, who admits he can't offer her much beyond "companionship." The television set is pushed on her by everyone who thinks it will provide relief from loneliness. The children only come round to something like acceptance of their mother's independence after she has broken off the engagement to the handsome, virile (and younger) Ron Kirby, and they have started new lives of their own: The daughter is getting married and the son is going off to work overseas. (In Iran! A reflection of different times.) No wonder Cary suffers psychosomatic headaches. I admit to having problems with the film's ending, in which she seemingly finds fulfillment only by devoting herself to nursing the now-vulnerable Ron back to health, as if a woman can only be useful by serving a man. But Sirk himself had problems with that ending, which was imposed on him by the producer, Ross Hunter. Sirk wanted more ambiguity about whether Ron would live or die.

All That Heaven Allows was ignored by the Academy, though Metty's cinematography certainly deserved notice -- it was probably judged a little too unconventional by his peers -- as did Frank Skinner's score, with its effective use of quotations from Liszt and Brahms and its resistance to melodramatic overstatement.

Watched on Turner Classic Movies