A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Anne Baxter. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Anne Baxter. Show all posts

Wednesday, May 15, 2019

The Blue Gardenia (Fritz Lang, 1953)

The Blue Gardenia (Fritz Lang, 1953)

Cast: Anne Baxter, Richard Conte, Ann Sothern, Raymond Burr, Jeff Donnell, George Reeves, Richard Erdman, Ruth Storey, Ray Walker, Nat "King" Cole. Screenplay: Charles Hoffman, based on a story by Vera Caspary. Cinematography: Nicholas Musuraca. Art direction: Charles D. Hall. Film editing: Edward Mann. Music: Raoul Kraushaar.

Thursday, August 24, 2017

A Royal Scandal (Otto Preminger, 1946)

|

| Charles Coburn, William Eythe, and Tallulah Bankhead in A Royal Scandal |

Chancellor Nicolai Ilyitch: Charles Coburn

Lt. Alexei Chernoff: William Eythe

Countess Anna Jaschikoff: Anne Baxter

Marquis de Fleury: Vincent Price

Capt. Sukov: Mischa Auer

Gen. Ronsky: Sig Ruman

Director: Otto Preminger

Screenplay: Edwin Justus Mayer, Bruno Frank

Based on a play by Lajos Biró and Melchior Lengyel

Cinematography: Arthur C. Miller

Costume design: René Hubert

Sometimes it's better not to know too much about a movie, for example the fact that A Royal Scandal was to be directed by Ernst Lubitsch and Greta Garbo almost made one of her many rumored comebacks as Catherine the Great. Might have been tends to distract us from what was: a more-than-passable comedy about the goings-on in the court of the Empress of all the Russias. It was a notorious flop, however, and essentially ended any hopes Tallulah Bankhead might have had for screen stardom after her much-praised performance in Lifeboat (Alfred Hitchcock, 1944). The film was savaged by the often unreliable but enormously influential Bosley Crowther in the New York Times: He called it "oddly dull and generally witless," though he faulted the script rather than Bankhead and the cast. I still think that if you go into A Royal Scandal with diminished expectations, you can find some fun in it. True, the script drags a little, and the central palace intrigue -- a plot to overthrow the empress -- is rather muddled in the setup. But it has some clever lines, and it has Bankhead and Charles Coburn to deliver them. William Eythe, a kind of second-string Tyrone Power, handles well his role as the naive soldier captivated by the empress, showing some shrewd comic timing, and Anne Baxter, as his fiancee and Catherine's lady-in-waiting, represses her tendency to overact. The faults in the film are generally more due to the director than the script. In Lubitsch's hands the romance might have been wittier and the comic-opera complications of the plot more effervescent. Otto Preminger, who took over after Lubitsch suffered a heart attack, was not the man for the job. As he showed with his first big hit, Laura (1944), Preminger was greatly gifted at handling scheming nasties and noirish perversities, but he was never one for costume-drama frivolities. What success he has with A Royal Scandal comes from giving a capable cast the reins.

Filmstruck

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942)

So much has been written about the mishandling and mutilation of Orson Welles's second feature film that it's hard to see the Magnificent Ambersons that we have without pining for the one we lost. What we have is a fine family melodrama with a truncated and sentimental happy ending and an undeveloped and poorly integrated commentary on the effects of industrialization on turn-of-the-20th-century America. We also have some of the best examples of Welles's genius at integrating performances, production design, and cinematography -- all of which Welles supervised to the point of micromanagement. The interior of the Amberson mansion is one of the great sets in Hollywood film: It earned an Oscar nomination for Albert S. D'Agostino, A. Roland Fields, and Darrell Silvera, though the credited set designer, Mark-Lee Kirk, should have been included. Welles used the set as a grand stage, exploiting the three levels of the central staircase memorably with the help of Stanley Cortez's deep-focus camerawork. Welles later told Peter Bogdanovich that Frank Lloyd Wright, who was Anne Baxter's grandfather, visited the set and hated it: It was precisely the kind of domestic architecture that he had spent his career trying to eliminate, which, as Welles said, was "the whole point" of the design. As for the performances, Agnes Moorehead received a supporting actress nomination, the first of four in her career, for playing the spinster aunt, Fanny Minafer. She's superb, especially in the "kitchen scene," a single long take in which her nephew, George (Tim Holt), scarfs down strawberry shortcake as she worms out of him the information that Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten) has renewed his courting of George's widowed mother, Isabel (Dolores Costello), which is especially painful for Fanny, who had hopes of attracting Eugene herself. Holt, an underrated actor, holds his own here and elsewhere -- he is, after all, the central character, the spoiled child whose selfishness ruins the chances for happiness of so many of the film's characters. We can mourn the loss of Welles's cinematic flourishes that were apparently cut from the film, but to my mind the chief loss is the effective integration of the theme initiated when Eugene, who has made his fortune developing the automobile, admits that the industrial progress it represents "may be a step backward in civilization" and that automobiles are "going to alter war and they're going to alter peace." Welles was speaking from his own life, as Patrick McGilligan observes in his book Young Orson. Welles's father, Dick Welles, had been involved in developing automobile headlights -- the very thing in which Fanny invests and loses her inheritance -- and was the proud driver of the first automobile on the streets of Kenosha, Wisconsin, Welles's home town. The Magnificent Ambersons would have been much richer if Welles had been able to make the statement about the automobile that he later told Bogdanovich was central to his concept of the film.

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950)

|

| Bette Davis and Thelma Ritter in All About Eve |

Eve Harrington: Anne Baxter

Addison DeWitt: George Sanders

Karen Richards: Celeste Holm

Bill Sampson: Gary Merrill

Lloyd Richards: Hugh Marlowe

Miss Casswell: Marilyn Monroe

Birdie: Thelma Ritter

Director: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Screenplay: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Based on a story by Mary Orr

Cinematography: Milton R. Krasner

Talk, talk, talk. Ever since the movies learned to do it, it has been the glory -- and sometimes the bane -- of the medium. We cherish some films because they do it so well: the films of Preston Sturges, Howard Hawks, and Quentin Tarantino, for example, would be nothing without their characters' abundantly gifted gab. Hardly a year goes by without someone compiling a list of the "greatest movie quotes of all time." And invariably the lists include such lines as "Fasten your seat belts, it's going to be a bumpy night" or "You have a point. An idiotic one, but a point." Those are spoken by, respectively, Margo Channing and Addison DeWitt in All About Eve, one of the movies' choicest collections of talk. Joseph L. Mankiewicz won the best screenplay Oscar for the second consecutive year -- he first won the previous year for A Letter to Three Wives, which, like All About Eve, he also directed -- and in both cases he received the directing Oscar as well. Would we admire Mankiewicz's lines as much if they had not been delivered by Bette Davis and George Sanders, along with such essential performers as Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter, and, in a small but stellar part, Marilyn Monroe? It could be said that Mankiewicz's dialogue tends to upend All About Eve: The glorious wisecracks and one-liners are what we remember about it, far more than its satiric look at the Broadway theater or its portrait of the ambitious Eve Harrington. We also remember the film as the continental divide in Bette Davis's career, the moment in which she ceased to be a leading lady and became the paradigmatic Older Actress, relegated more and more to character roles and campy films like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Robert Aldrich, 1962). All About Eve, in which Margo turns 40 -- Davis was 42 -- and ever so reluctantly hands over the reins to Eve -- Baxter was 27 -- is a kind of capitulation, an unfortunate acceptance that a female actor's career has passed its peak, when in fact all that is needed is writers and directors and producers who are willing to find material that demonstrates the ways in which life goes on for women as much as for men.

Thursday, March 31, 2016

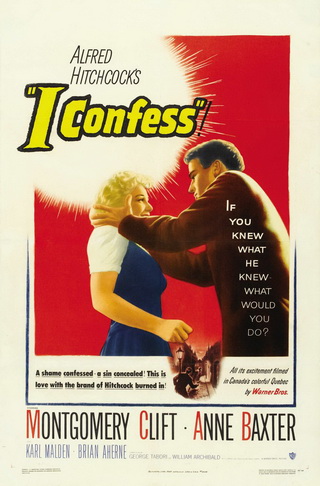

I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock, 1953)

I Confess is generally recognized as lesser Hitchcock, even though it has a powerhouse cast: Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, and Karl Malden. It also has the extraordinary black-and-white cinematography of Robert Burks, making the most of its location filming in Québec. Add to that a provocative setup -- a priest learns the identity of a murderer in confession but is unable to reveal it even when he is put on trial for the murder -- and it's surprising that anything went wrong. I think part of the reason for the film's weakness may go back to the director's often-quoted remark that actors are cattle. This is not the place to discuss whether Hitchcock actually said that, which has been done elsewhere, but the phrase has so often been associated with him that it reveals something about his relationship with actors. It's clear from Hitchcock's recasting of certain actors -- Cary Grant, James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Ingrid Bergman -- that he was most comfortable directing those he could trust. And Clift's stiffness and Baxter's mannered overacting suggest that Hitchcock felt no particular rapport with them. But I Confess also played directly into the hands of the censors: The Production Code was administered by Joseph Breen, a devout Catholic layman, and routinely forbade any material that reflected badly on the clergy. In the play by Paul Anthelme and the first version of the screenplay by George Tabori, the priest (Clift) and Ruth Grandfort (Baxter) have had a child together, and the murdered man (Ovila Légaré) is blackmailing them. Moreover, because he is prohibited from revealing what was told him in the confessional and naming the real murderer (O.E. Hasse), the priest is convicted and executed. Warner Bros., knowing how the Breen office would react, insisted that the screenplay be changed, and when Tabori refused, it was rewritten by William Archibald. The result is something of a muddle. Why, for example, is the murderer so scrupulous about confessing to the priest when he later has no hesitation perjuring himself in court and then attempting to kill the priest? No Hitchcock film is unwatchable, but this one shows no one, except Burks, at their best.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Swamp Water (Jean Renoir, 1941)

Swamp Water has a few things working against it other than its title. For one, having a cast of familiar Hollywood stars pretending to be farmers, hunters, and trappers living on the edge of the Okefenokee swamp, and saying things like "I brung her" and "He got losted," makes for a certain lack of authenticity. And at 32, its leading man, Dana Andrews is about a decade too old to be playing the callow youth he's supposed to be in the movie. Add to that the director, Jean Renoir, is a wartime exile from France, making his first film in Hollywood, and you might expect the worst. Fortunately, it has a screenplay by a master, Dudley Nichols, and an eminently watchable cast that includes Walter Brennan, Walter Huston, Anne Baxter, John Carradine, Ward Bond, and Eugene Pallette, who while they may never quite convince us that they're Georgia swamp-folk, do their professional best. It turns out to be a thoroughly entertaining movie that, while it doesn't add any luster to Renoir's career, doesn't detract from it either. This was Andrews's second year in movies, and he gives the kind of energetic performance that mostly overcomes miscasting. Born in Mississippi and raised in Texas, he also seems to know the character he's called on to play, perhaps a little better than the city-bred Baxter, whose efforts at being the village outcast are a bit forced. Brennan as usual plays an old coot, but without overdoing the mannerisms -- it's a slyly engaging performance. Much of the footage was shot by cinematographer J. Peverell Marley and the uncredited Lucien Ballard in the actual swamp and environs near Waycross, Georgia. There is some obvious failure to match the location footage with that shot back in the 20th Century-Fox studio, but it's not terribly distracting.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)