A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Birgitte Federspiel. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Birgitte Federspiel. Show all posts

Thursday, April 27, 2017

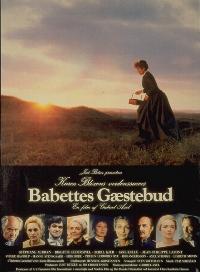

Babette's Feast (Gabriel Axel, 1987)

I had an odd experience this morning when I sat down to write this blog entry: I couldn't remember what film I watched last night. Ordinarily I'd ascribe this memory lapse to a "senior moment," but once I remembered that the film was Gabriel Axel's Babette's Feast, I thought I knew what caused it. This is what I call a "mood movie," one that, like some pieces of music, is designed -- or perhaps better, destined -- to put you into a certain emotional state. In the case of Babette's Feast, it's a kind of sweet melancholy, a state so ephemeral that almost anything can sweep it away -- as my experience of Babette's Feast was wiped away when I watched Survivor and Marvel's Agents of Shield, not exactly sweetly melancholic shows, immediately afterward on TV. This is not meant as a knock on Gabriel Axel's film, the screenplay for which he adapted from a story by Karin Blixen (aka Isak Dinesen). After all, it won the Oscar for best foreign language film, beating out among other contenders Louis Malle's Au Revoir les Enfants. It does what it does extraordinarily well, which is to tell a story, evoke a particular time and place, and present us with memorable characters. It centers on two sisters, Filippa (Bodil Kjer) and Martine (Birgitte Federspiel), who live in a small Danish village where they tend to the aging congregation of a small, austere sect which their father gathered together many years ago. A kindly man, he nevertheless dominated their lives to the extent that suitors were discouraged from marrying them. One of Filippa's suitors was an aging French operatic baritone, Achille Papin (Jean-Philippe Lafont), who was traveling through the village and happened to hear her singing in the church. Smitten with both her beauty and her voice, he offered to give her singing lessons, but when he proposed to take her to Paris and make her a diva, she took fright and turned him down. Some years later, during the unrest in Paris after the fall of the Second Empire in 1871, Papin sends to the sisters a young woman whose life has been threatened. Her name is Babette Hersant, his letter tells them, and she's an excellent cook who would be a fine housekeeper for them. Babette (Stéphane Audran) takes up residence with them and proves to be invaluable, bringing Parisian skills at seeking out the best food in the markets and bargaining for the best price. And then one day Babette receives word that an old lottery ticket has finally paid off to the tune of 10,000 francs. It is also the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the small congregation, and Babette proposes that she cook a dinner for the elderly, cranky, often fractious flock to celebrate. What the sisters don't know, but will soon learn, is that Babette had been one of the most celebrated chefs in Paris. The film climaxes in a triumphant union of the spiritual and the physical, as Babette's feast transforms the group into a true fellowship. Axel stages the feast beautifully, and cinematographer Henning Kristiansen emphasizes the transformation wrought by Babette's food with a steady focus on the faces of the congregants, which change from icy gray to rosy warmth as the meal progresses. There's a lovely little moment in which one of the sternest of the group reaches for a glass, discovers that it's filled with water, makes a face, and eagerly picks up a wine glass instead. As I've said, it's an ephemeral film, and I certainly don't think it deserved the Oscar over the more complex and powerful Au Revoir les Enfants, but on the other hand, what's so bad about feeling good?

Monday, June 13, 2016

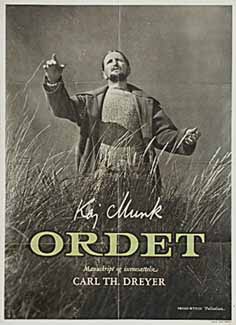

Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

As a non-believer, I find the story told by Ordet objectively preposterous, but it raises all the right questions about the nature of religious belief. Ordet, the kind of film you find yourself thinking about long after it's over, is about the varieties of religious faith, from the lack of it, embodied by Mikkel Borgen (Emil Hass Christensen), to the mad belief of Mikkel's brother Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) that he is in fact Jesus Christ. Although Mikkel is a non-believer, his pregnant wife, Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), maintains a simple belief in the goodness of God and humankind. The head of the Borgen family, Morten (Henrik Malberg), regularly attends church, but it's a relatively liberal modern congregation, headed by a pastor (Ove Rud), who tries to be forward-thinking: He denies the possibility of miracles in a world in which God has established physical laws, although he doesn't have a ready answer when he's asked about the miracles in the Bible. When Morten's youngest son, Anders (Cay Kristiansen), falls in love with a young woman, her father, Peter (Ejner Federspiel), who belongs to a very conservative sect, forbids her to marry Anders. Then everyone's faith or lack of it is put to test when Inger goes into labor. The doctor (Henry Skjaer) thinks he has saved her life by aborting the fetus -- we are told that it has to be cut into four pieces to deliver it -- but after he leaves, Inger dies. As she is lying in her coffin, Peter arrives to tell Morten that her death has made him realize his lack of charity and that Anders can marry his daughter. And as if this doesn't sound conventionally sentimental enough, the film ends with Inger, who has died in childbirth, being restored to life with the help of Johannes and the simple faith of her young daughter. Embracing Inger, Mikkel now proclaims that he is a believer. The conundrum of faith and evidence runs through the film. For example, if the only thing that can restore one's faith is a miracle, can we really call that faith? What makes Ordet work -- in fact, what makes it a great film -- is that it poses such questions without attempting answers. It subverts all our expectations about what a serious-minded film about religion -- not the phony piety of Hollywood biblical epics -- should be. Dreyer and cinematographer Henning Bendtsen keep everything deceptively simple: Although the film takes place in only a few sparely decorated settings, the reliance on very long single takes and a slowly traveling camera has a documentary-like effect that engages a kind of conviction on the part of the audience that makes the shock of Inger's resurrection more unsettling. We don't usually expect to find our expectations about the way things are -- or the way movies should treat them -- so rudely and so provocatively exploded.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)