A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Henning Bendtsen. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Henning Bendtsen. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 14, 2016

Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964)

Imagine Gertrud as a Hollywood "women's picture" of the 1940s or '50s, with Olivia de Havilland, perhaps, as Gertrud, and Claude Rains as her husband, Montgomery Clift as her young lover, and Walter Pidgeon as the old flame who comes back into her life. It's not hard to do, given that the play by Hjalmar Söderberg on which Carl Theodor Dreyer based his film has all the elements of the genre: a woman trapped in a sterile marriage; an ardent young lover who appeals to the artist trapped in her; another man who represents the road not taken that might have led her to fulfillment if she hadn't discovered that he was more committed to his work than to her. And it ends the way the Hollywood film might have: After Gertrud has rejected those three lovers and gone off to Paris with yet another man -- George Brent, perhaps -- who seemed to give her the opportunity to find herself, we see them reunite 30 or 40 years later, when she has settled into a sadly contented solitary life. There would have been a Max Steiner or Alfred Newman score to draw tears at the crisis moments -- as when, for example, Gertrud discovers that her young lover has boasted of his affair with her at a party also attended by the old flame. But this is a "women's picture" of ideas, largely about the nature of love and the way we can be deceived in the pursuit of it. And there are no melodramatic moments, merely extended conversations in which the participants rarely, if ever, make eye contact. As Gertrud, Nina Pens Rode maintains a gaze into the middle distance, rarely even blinking, whether she's telling her husband (Bendt Rothe) that she's leaving him, declaring her love for the young musician (Baard Owe) who later boasts of his conquest, or reminiscing about their past together with her old flame (Ebbe Rode). But the faint flicker of thought and emotion always plays over her face, as Henning Bendtsen's camera gazes steadily at her. It is, for those raised on the Hollywood version, something of a trying and even boring film, but for those who understand what Dreyer is doing -- grabbing the viewer's eye and keeping it trained on the characters, through long, long takes and subtle camera moments -- it creates a psychological tension that is unnerving. Dreyer makes more conventional directors' work seem frantic and frivolous.

Monday, June 13, 2016

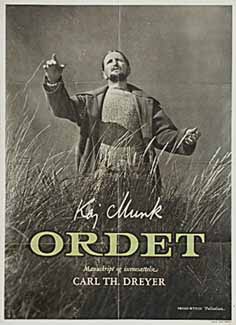

Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

As a non-believer, I find the story told by Ordet objectively preposterous, but it raises all the right questions about the nature of religious belief. Ordet, the kind of film you find yourself thinking about long after it's over, is about the varieties of religious faith, from the lack of it, embodied by Mikkel Borgen (Emil Hass Christensen), to the mad belief of Mikkel's brother Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) that he is in fact Jesus Christ. Although Mikkel is a non-believer, his pregnant wife, Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), maintains a simple belief in the goodness of God and humankind. The head of the Borgen family, Morten (Henrik Malberg), regularly attends church, but it's a relatively liberal modern congregation, headed by a pastor (Ove Rud), who tries to be forward-thinking: He denies the possibility of miracles in a world in which God has established physical laws, although he doesn't have a ready answer when he's asked about the miracles in the Bible. When Morten's youngest son, Anders (Cay Kristiansen), falls in love with a young woman, her father, Peter (Ejner Federspiel), who belongs to a very conservative sect, forbids her to marry Anders. Then everyone's faith or lack of it is put to test when Inger goes into labor. The doctor (Henry Skjaer) thinks he has saved her life by aborting the fetus -- we are told that it has to be cut into four pieces to deliver it -- but after he leaves, Inger dies. As she is lying in her coffin, Peter arrives to tell Morten that her death has made him realize his lack of charity and that Anders can marry his daughter. And as if this doesn't sound conventionally sentimental enough, the film ends with Inger, who has died in childbirth, being restored to life with the help of Johannes and the simple faith of her young daughter. Embracing Inger, Mikkel now proclaims that he is a believer. The conundrum of faith and evidence runs through the film. For example, if the only thing that can restore one's faith is a miracle, can we really call that faith? What makes Ordet work -- in fact, what makes it a great film -- is that it poses such questions without attempting answers. It subverts all our expectations about what a serious-minded film about religion -- not the phony piety of Hollywood biblical epics -- should be. Dreyer and cinematographer Henning Bendtsen keep everything deceptively simple: Although the film takes place in only a few sparely decorated settings, the reliance on very long single takes and a slowly traveling camera has a documentary-like effect that engages a kind of conviction on the part of the audience that makes the shock of Inger's resurrection more unsettling. We don't usually expect to find our expectations about the way things are -- or the way movies should treat them -- so rudely and so provocatively exploded.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)