|

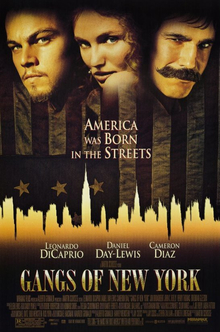

| Daniel Day-Lewis, Winona Ryder, Geraldine Chaplin, and Michelle Pfeiffer in The Age of Innocence |

Newland Archer: Daniel Day-Lewis

Ellen Olenska: Michelle Pfeiffer

May Welland: Winona Ryder

Larry Lefferts: Richard E. Grant

Sillerton Jackson: Alec McCowen

Mrs. Welland: Geraldine Chaplin

Regina Beaufort: Mary Beth Hurt

Julius Beaufort: Stuart Wilson

Mrs. Mingott: Miriam Margolyes

Mrs. Archer: Siân Phillips

Henry van der Luyden: Michael Gough

Louisa van der Luyden: Alexis Smith

Mr. Letterblair: Norman Lloyd

Rivière: Jonathan Pryce

Ted Archer: Robert Sean Leonard

Narrator: Joanne Woodward

Director: Martin Scorsese

Screenplay: Jay Cocks, Martin Scorsese

Based on a novel by Edith Wharton

Cinematography: Michael Ballhaus

Production design: Dante Ferretti

Film editing: Thelma Schoonmaker

Costume design: Gabriella Pescucci

Music: Elmer Bernstein

Voiceover narrators in movies are usually to be avoided: They often serve as a crutch for screenwriters and directors who can't tell their stories through dialogue and action. But Joanne Woodward's cool, wry, witty narrator in

The Age of Innocence is an essential element: She's really playing Edith Wharton, or more properly the "narrative voice," the storyteller who is there to comment on and clarify the characters and their motives and backstories. It's a device, and a performance, that brings us closer to the source of the movie. Whether that's a good thing or not is subject to debate: Many think that trying to squeeze one medium, literature, together with another, motion pictures, does a disservice to both art forms. Still,

The Age of Innocence does it better than most literary movies, including much of the late flood of Jane Austen adaptations and even some of the Merchant Ivory

oeuvre. The chief criticism of the film is that it's over-upholstered, that the attention devoted to period detail tends to overwhelm the story. But Martin Scorsese assembled a cast that could upstage all the fabric and cutlery and crockery, starting with Woodward, but of course including the three stars on screen, Daniel Day-Lewis, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Winona Ryder, and extending to one of the best supporting casts ever mustered. My criticism is that the film is overlong, coming in at 139 minutes. I don't begrudge the time spent watching that cast, but the film does Wharton's story a disservice by making it seem more portentous than it is. Epic length in movies is justified if the topic demands it, like the Russian stand against Napoleon in Sergey Bondarchuk's

War and Peace (1966) or the struggle to unite Italy in Luchino Visconti's

The Leopard (1963), to name two of the more successful historical epics. But Wharton was working, like Austen on her "little bit (two inches wide) of ivory," in comparative miniature, with a thin slice of history in which manners and morals, not countries and continents, were undergoing revolutionary change. Fiction like Wharton's is meditative, film like Scorsese's is visceral, and while narration like Woodward's allows for some of the first, what lives with us after the film ends is likely to be the impact of Dante Ferretti's production design, Gabriella Pescucci's Oscar-winning costumes, Elmer Bernstein's score, and especially Michael Ballhaus's images, not to mention the pleasure of watching Day-Lewis, Pfeiffer, Ryder,

et al. at peak performance.