A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Steven Zaillian. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Steven Zaillian. Show all posts

Thursday, December 5, 2019

The Irishman (Martin Scorsese, 2019)

The Irishman (Martin Scorsese, 2019)

Cast: Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, Harvey Keitel, Ray Romano, Bobby Canavale, Anna Paquin, Stephen Graham, Stephanie Kurtzuba, Jack Huston, Kathrine Narducci, Jesse Plemons, Dominick Lombardozzi, Paul Herman, Gary Basaraba. Screenplay: Steven Zaillian, based on a book by Charles Brandt. Cinematography: Rodrigo Prieto. Production design: Bob Shaw. Film editing: Thelma Schoonmaker. Music: Robbie Robertson.

The Irishman feels valedictory, and not just because it's about gangsters growing old, but also because it's about the kind of gangsters Martin Scorsese and others introduced us to as well as the aging actors who played them: De Niro, Pacino, Pesci, Keitel. And also because it feels like Scorsese's farewell to conventional theatrical release. Movie theaters today thrive on the kind of blockbusters Scorsese has recently dismissed as "not cinema" and more like theme parks. His collaboration with the king of home streaming services, Netflix, seems to announce that a new era of movie distribution and exhibition has arrived -- one in which the old limitations of film content and even length no longer apply. Scorsese recently said that The Irishman's three-and-a-half-hour length would probably hinder its release in today's theaters, where the only movies that long are ones like the three-hour Avengers: Endgame, a "theme park" movie. Exhibitors want films that fit tightly into a schedule, which discourages producers from making epic-length features like Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962). Netflix audiences, on the other hand, can watch on their own time, with the leisure to interrupt the film at any point for a snack or bathroom break. So a movie like The Irishman, which has an epic length but also a subtle, intimate treatment of its characters, doesn't fit in today's theaters. What's lost, of course, is the communal experience of moviegoing, the sharing by complete strangers of dreams in the dark. But we should be glad that anything makes movies like The Irishman possible. I don't know if it's a "masterpiece," as some enthusiasts have called it, but it's a damn good movie, with the best performances by De Niro and Pacino in years, and a wonderful return from semi-retirement by Pesci, who tamps down his usual ebullience for a quietly sinister but also, in later scenes, touching portrayal of a mob manipulator. The whole thing is a kind of morality tale, with De Niro's Frank Sheeran paying for his many sins by waiting for death in an existential loneliness. It takes a wizard like Scorsese -- helped by Steven Zaillian's screenplay -- to keep that kind of fable from going mawkish and sentimental.

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

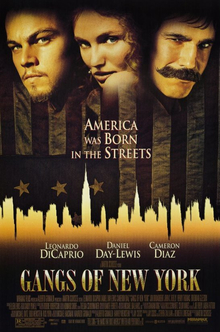

Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese, 2002)

Gangs of New York is such a sprawling, unfocused movie that I can almost imagine the filmmakers throwing up their hands and sighing, "Well, at least we've got Daniel." Because Daniel Day-Lewis's performance as Bill "The Butcher" Cutting holds the film together whenever it tends to sink into the banality of its revenge plot or to wander off into the eddies of New York City history. A historical drama like Gangs of New York needs two things: a compelling central story and an audience that knows something about the history on which it's based. But for all their violence and their anticipation of problems that continue to manifest themselves in the United States, the Draft Riots of 1863 and the almost two decades of gang wars that led up to them are mostly textbook footnotes to most Americans. Director Martin Scorsese's determination to depict them led to the hiring of a formidable team of screenwriters -- Jay Cocks, who wrote the story, and Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan, who collaborated with Cocks on the screenplay. Unfortunately, the narrative thread that they came up with is tired. As a boy, Amsterdam Vallon saw his father, an Irish Catholic nicknamed "Priest" (Liam Neeson), cut down by Bill the Butcher in a huge battle between the Irish immigrant gang, the Dead Rabbits, and Bill's Protestant gang, the Natives. Sixteen years later Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) returns to the Five Points neighborhood determined to get revenge on Bill, who has managed to make peace with many of the old members of Vallon's father's gang and to become a power-player aligned with Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent). Vallon is introduced to Bill's criminal enterprise by an old boyhood friend, Johnny (Henry Thomas), and he begins to fall under Bill's spell -- along with that of a pretty pickpocket, Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz). But the relationship between Vallon and Jenny stirs the jealousy of Johnny, who is smitten with her, and he reveals to Bill that Vallon is the son of his old enemy, leading to a climactic showdown -- one that just happens to occur simultaneously with the Draft Riots. There's a lot of good stuff in Gangs of New York, including Michael Ballhaus's cinematography and Dante Ferretti's production design -- the sets were constructed at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. But the awkward attempt to merge the romantic revenge plot with the historical background shifts the focus away from what the film is supposedly about: racism, anti-immigrant nativism, political corruption, and exploitation of the poor. "You can always hire one half of the poor to kill the other half," Tweed says. Oddly (and sadly), Gangs of New York seems more relevant today than it did in 2002, when the country was recovering from the 9/11 attacks. Then, the Oscar-nominated anthem by U2, "The Hands That Built America," which concludes the film seemed to promise a spirit of unity, an affirmation that the country had overcome the antagonisms depicted in the movie. Today it has a far more ironic effect.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)