A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Henry Thomas. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Henry Thomas. Show all posts

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

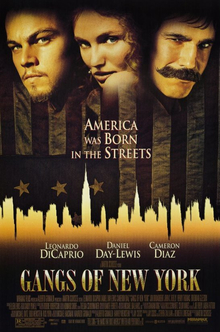

Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese, 2002)

Gangs of New York is such a sprawling, unfocused movie that I can almost imagine the filmmakers throwing up their hands and sighing, "Well, at least we've got Daniel." Because Daniel Day-Lewis's performance as Bill "The Butcher" Cutting holds the film together whenever it tends to sink into the banality of its revenge plot or to wander off into the eddies of New York City history. A historical drama like Gangs of New York needs two things: a compelling central story and an audience that knows something about the history on which it's based. But for all their violence and their anticipation of problems that continue to manifest themselves in the United States, the Draft Riots of 1863 and the almost two decades of gang wars that led up to them are mostly textbook footnotes to most Americans. Director Martin Scorsese's determination to depict them led to the hiring of a formidable team of screenwriters -- Jay Cocks, who wrote the story, and Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan, who collaborated with Cocks on the screenplay. Unfortunately, the narrative thread that they came up with is tired. As a boy, Amsterdam Vallon saw his father, an Irish Catholic nicknamed "Priest" (Liam Neeson), cut down by Bill the Butcher in a huge battle between the Irish immigrant gang, the Dead Rabbits, and Bill's Protestant gang, the Natives. Sixteen years later Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) returns to the Five Points neighborhood determined to get revenge on Bill, who has managed to make peace with many of the old members of Vallon's father's gang and to become a power-player aligned with Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent). Vallon is introduced to Bill's criminal enterprise by an old boyhood friend, Johnny (Henry Thomas), and he begins to fall under Bill's spell -- along with that of a pretty pickpocket, Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz). But the relationship between Vallon and Jenny stirs the jealousy of Johnny, who is smitten with her, and he reveals to Bill that Vallon is the son of his old enemy, leading to a climactic showdown -- one that just happens to occur simultaneously with the Draft Riots. There's a lot of good stuff in Gangs of New York, including Michael Ballhaus's cinematography and Dante Ferretti's production design -- the sets were constructed at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. But the awkward attempt to merge the romantic revenge plot with the historical background shifts the focus away from what the film is supposedly about: racism, anti-immigrant nativism, political corruption, and exploitation of the poor. "You can always hire one half of the poor to kill the other half," Tweed says. Oddly (and sadly), Gangs of New York seems more relevant today than it did in 2002, when the country was recovering from the 9/11 attacks. Then, the Oscar-nominated anthem by U2, "The Hands That Built America," which concludes the film seemed to promise a spirit of unity, an affirmation that the country had overcome the antagonisms depicted in the movie. Today it has a far more ironic effect.

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982)

There are movies you can watch over and over, either to savor something you hadn't particularly noticed before or in delighted anticipation of favorite parts. And then there are movies that you wish you could watch the way you did the first time you saw them, with surprise and exhilaration. I first saw E.T. in the summer of its initial release, with my wife and 8-year-old daughter in a theater in Chestnut Hill, Mass. It was an unspoiled delight, not layered over with the years' accretions of commentary and critique. I can never again see the movie that we saw that afternoon in Chestnut Hill. Watching it last night for the first time in years, I found that the best thing about it is that it brought back faint memories of the initial experience. It hasn't grown in my estimation, but on the other hand it also hasn't diminished very much. Spielberg is one of the great cinematic storytellers, particularly in his ability to narrate without words -- a gift that began to vanish from filmmaking with the arrival of sound almost 90 years ago. The opening of the film, with the scurrying, botanizing aliens and the clumsy, sinister humans who want to spy on them, is a near perfect example of showing instead of telling, and Spielberg's use of that technique is threaded throughout the movie. He also knows how to direct people, even precocious actors like Henry Thomas, Drew Barrymore, and Robert MacNaughton, who are utterly convincing in the way that movie kids rarely were before E.T. and seldom have been since. Yes, there are sequences that don't quite work, like the liberation of the frogs in the science class, and the special effects, such as the kids on the flying bicycles, look antiquated. The appearance of the resuscitated E.T., shrouded in a sheet and with a glowing heart, evoking Christian iconography, is a serious misstep. There are times when the John Williams score verges on overkill. And it undeniably helped set the film industry off in the wrong direction away from making movies for adults and toward crowd-pleasers. But all of that is part of the accretion of time. There is a timeless core to E.T. that helps it secure its place among the great movies.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)