|

| James Caan, Robert Mitchum, Arthur Hunnicutt, and John Wayne in El Dorado |

J.P. Harrah: Robert Mitchum

Mississippi: James Caan

Bull: Arthur Hunnicutt

Maudie: Charlene Holt

Dr. Miller: Paul Fix

Josephine (Joey) MacDonald: Michele Carey

Bart Jason: Edward Asner

Neise McLeod: Christopher George

Kevin MacDonald: R.G. Armstrong

Luke MacDonald: Johnny Crawford

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: Leigh Brackett

Based on a novel by Harry Brown

Cinematography: Harold Rosson

Art direction: Carl Anderson, Hal Pereira

Film editing: John Woodcock

Music: Nelson Riddle

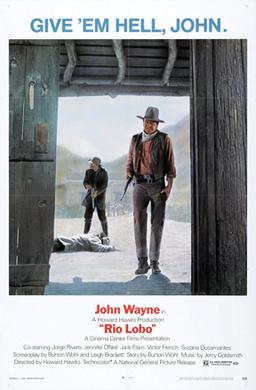

Like his later Rio Lobo (1970), Howard Hawks's El Dorado isn't so much a remake of his Rio Bravo (1959) as a movie built on its template: Gunfighter John Wayne teams up with a drunken sheriff, a greenhorn, and an old coot to stand off an assault by the bad guys, who greatly outnumber them. Wayne retains his earlier role in El Dorado, but here the drunken sheriff is Robert Mitchum, the greenhorn is James Caan, and the old coot is Arthur Hunnicutt, replacing Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, and Walter Brennan, respectively, in the earlier film. Unfortunately, Hawks was unable to find a suitable replacement for Angie Dickinson's Feathers, the "Hawksian woman" in Rio Bravo, and tried without much success to sub in two C-list actresses, Charlene Holt as Maudie, the woman with a past that involves both Wayne and Mitchum, and Michele Carey as the hoydenish Joey. Neither makes the impression that Dickinson made. Leigh Brackett was disappointed to find that Hawks had turned her screenplay into a reworking of Rio Bravo, but she was used to his freewheeling ways by then, having worked for him on The Big Sleep (1946) and Hatari! (1962). There are diminishing returns to any kind of remake, and by the time Hawks made Rio Lobo, the template had worn thin, but El Dorado is solid enough entertainment, especially when Wayne and Mitchum are on screen together, playing off of each other gleefully. Except for the rather hackneyed "El Dorado" theme song over the opening credits, with its by-the-numbers lyrics by John Gabriel, Nelson Riddle's score is a pleasant surprise in its avoidance of Western movie clichés -- no cowboy songs or "Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie." The one sour note in the movie comes when Caan puts on a racial-caricature "Chinaman" act to get the jump on a lurking gunman.