A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, September 15, 2016

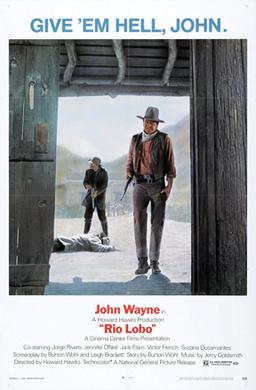

Rio Lobo (Howard Hawks, 1970)

Not much of the opening sequence of Rio Lobo, an exciting and ingenious train robbery, was probably directed by Howard Hawks. He was injured during the filming, and much of it was accomplished by his second-unit directors, Yakima Canutt and Mike Moder, who are generously given screen credits -- just as Hawks gave a co-director credit to Arthur Rosson for the cattle drive scenes in Red River (1948). The sequence is also the best thing in the film. What follows feels for the most part tired, derivative, and poorly cast, which is a shame, since it was Hawks's last film. We'd all like our favorite directors to go out on a high note, but it seldom happens: There aren't many who regard Alfred Hitchcock's Family Plot (1976), Billy Wilder's Buddy Buddy (1981), or John Ford's 7 Women (1966) as sufficiently valedictory achievements, either. Still, Rio Lobo has its moments, most of them supplied by old pros like John Wayne and Jack Elam. It has cinematography by the masterly William H. Clothier and a score by Jerry Goldsmith. What it doesn't have is a competent supporting cast, particularly in the key roles played by Jorge Ribero and Jennifer O'Neill. Ribero's success in Mexican films, combined with his good looks, led Hollywood to give him a try, but he's out of his depth as a foil for Wayne and is obviously uncomfortable in his second language. O'Neill, a former model, is the last in the line of "Hawksian women" whose ability to stand up to men gave a certain bright tension to his films, and who were previously embodied by the likes of Katharine Hepburn, Jean Arthur, Rosalind Russell, and Lauren Bacall. But when O'Neill flubs an attempt to match Wayne at Hawks's characteristic overlapping repartee, it's clear that the game is over. O'Neill's character virtually disappears from the later part of the film, and the climactic scene is given to another character played by Sherry Lansing, who at least recognized her limitations as an actress and gave it up to become a film studio executive. Rio Lobo, a more or less acknowledged semi-remake of Rio Bravo (1959) and its remake, El Dorado (1966), is not without its rewards for those who relish old-style Westerns, but coming from an era when Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah were reinventing the genre it feels like a sad anachronism.