Daybreak, the Anglicized title of Marcel Carné's Le Jour Se Lève, recalls another great attempt at poetic cinema, F.W. Murnau's late silent Sunrise (1927). But where Murnau strove for a kind of allegorical poetry, to the extent of labeling his characters The Man, The Wife, and The Woman From the City, Carné's poetry is rooted in actuality. Jean Gabin plays François, a factory worker who falls in love with Françoise (Jacqueline Laurent), who works in a flower shop. He follows her one night to a music hall, where she watches an act by the animal trainer Valentin (Jules Berry). At the bar, he strikes up a conversation with Clara (Arletty), who was Valentin's stage assistant but has just broken up with him. When he discovers that Françoise is infatuated with Valentin, François lets himself be drawn into a relationship with Clara. Eventually this quartet of relationships will turn fatal. But Carné and his screenwriters Jacques Viot and Jacques Prévert choose to tell the story in flashbacks: The film begins with François shooting Valentin and then holing up in his apartment as the police lay siege to it, trying to arrest him. The film superbly mixes suspense, as we wait for the outcome of François's standoff with the police, with romance, as we learn of the affairs with Françoise and Clara that brought him to this point. It's often cited as a precursor of film noir for its mixture of passion and violence. Gabin is the quintessential world weary protagonist, Berry the embodiment of corruption, and Arletty the woman who's seen it all too often.

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Jules Berry. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jules Berry. Show all posts

Friday, March 21, 2025

Le Jour Se Lève (Marcel Carné, 1939)

Cast: Jean Gabin, Jules Berry, Arletty, Jacqueline Laurent, Mady Berry, René Génin, Arthur Devère, René Bergeron, Bernard Blier, Marcel Pérès, Germaine Lix, Gabrielle Fontan, Jacques Baumer. Screenplay: Jacques Viot, Jacques Prévert. Cinematography: Philippe Agostini, André Bac, Albert Viguier, Curt Courant. Production design: Alexandre Trauner. Film editing: René Le Hénauff. Music: Maurice Jaubert.

Sunday, September 16, 2018

Les Visiteurs du Soir (Marcel Carné, 1942)

|

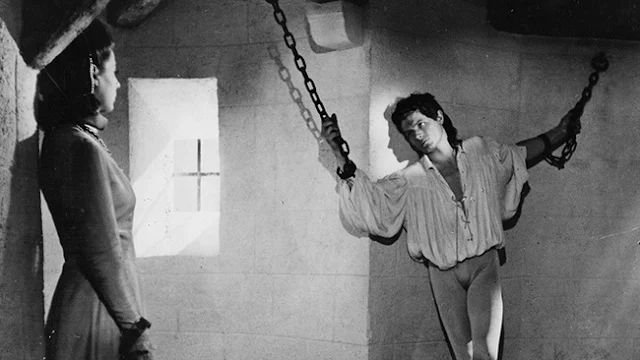

| Marie Déa and Alain Cuny in Les Visiteurs du Soir |

Gilles: Alain Cuny

Anne: Marie Déa

Baron Hugues: Fernand Ledoux

Renaud: Marcel Herrand

The Devil: Jules Berry

Director: Marcel Carné

Screenplay: Jacques Prévert, Pierre Laroche

Cinematography: Roger Hubert

Production design: Alexandre Trauner

Film editing: Henri Rust

Music: Joseph Kosma, Maurice Thiriet

Alexandre Trauner's sets and costumes for Marcel Carné's Les Visiteurs du Soir were based on the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, although I was more reminded of the work of early 20th century illustrators like Walter Crane, N.C. Wyeth, and Maxfield Parrish, who were also influenced by that celebrated 15th-century illuminated manuscript. Trauner was not credited for his work on the film however. He was a Jew in occupied France, and the credit went to a "front," Georges Wakhévitch, just as, little more than a decade later, blacklisted Americans working in Hollywood were forced to hide behind their own fronts. The story of the making of Les Visiteurs du Soir is almost as interesting as the film itself.Not only was some of the behind-the-scenes work done sub rosa, to fool the Nazis and their collaborators, even the film's attempts to display luxury were thwarted by real-life conditions. Although the film was given a generous budget, the costuming was hindered by a shortage of suitable fabric, and in the banquet scenes the food had to be treated with an unpleasant substance to keep the extras and the crew from gobbling it down between takes. Even so, because the film deals with the manipulations of emissaries from the devil to the court of a French nobleman, it was taken to be a kind of allegory of the German invasion of France, and the devil played by Jules Berry to be a satirical representation of Adolf Hitler. The director and the screenwriters denied that was their intent.The film was a big critical and commercial hit in a France starved for movies -- films made in America and Britain were banned -- and while it's not on a par with Carné's 1945 masterpiece Children of Paradise, it remains a classic. Arletty is superbly seductive as Dominique, although it's doubtful that anyone would ever mistake her for the boy she pretends to be for part of the film. Trouser roles are always a problematic convention, but Arletty's "boy" looks to be in his 40s, which she was. As her fellow emissary, Alain Cuny is suitably dashing, and while Marie Déa is not quite the peerless beauty the screenplay wants her to be, the doomed love affair of Anne and Gilles gives an otherwise rather chilly film some warmth. But the film is stolen by Jules Berry as the devil, camping it up amusingly, at one point literally playing with fire. As a fantasy film, Les Visiteurs du Soir doesn't have the consummate style of Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast (1946), to which it is sometimes compared, but its moods are darker and its story may be deeper.

Sunday, July 30, 2017

Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (Jean Renoir, 1936)

|

| René Lefèvre in Le Crime de Monsieur Lange |

Valentine: Florelle

Batala: Jules Berry

The Concierge: Marcel Lévesque

The Concierge's Wife: Odette Talazac

Meunier's Son: Henri Guisol

Charles: Maurice Baquet

Edith: Sylvia Bataille

Estelle: Nadia Sibirskaia

Director: Jean Renoir

Screenplay: Jean Castanier, Jacques Prévert, Jean Renoir

Cinematography: Jean Bachelet

M. Lange's crime is murder, and he gets away with it. This droll dark comedy is a vehicle for Jean Renoir's anti-fascist politics, and to enjoy it to the fullest you probably have to have been there -- "there" being Europe in 1936. But it still resonates 80-plus years later with its story of a little guy exploited by a venal fat cat. Lange, who writes adventure stories about "Arizona Jim" in the wild West, works for a greedy, corrupt publisher named Batala, who not only stiffs him on a contract to publish the stories, but also inserts advertising plugs into the story itself, making Arizona Jim pause to pop one of the sponsor's pills before launching into action. Batala is also a shameless womanizer who impregnates Estelle, the girlfriend of Charles, the bicycle messenger who works for him. (In a rather cold-hearted twist you probably won't see in movies today, everyone rejoices when the baby dies.) Fleeing from his creditors, Batala reportedly dies in a train wreck, and to salvage their jobs, his employees, encouraged by Meunier, the son of Batala's chief creditor, form a cooperative to run the publishing company. It's a huge success, with Lange's stories becoming incredibly popular -- so much so that a film company wants to buy the rights to make an Arizona Jim movie. Unfortunately, Lange doesn't own the rights, as Batala reveals when he turns up very much alive, disguised as a priest who happened to be standing by him during the crash. When Batala begins demonstrating his old ways, including making a play for all the available women in the company as well as asserting his rights to Arizona Jim and the profits it has made, Lange shoots him, then flees with his girlfriend Valentine. Aided by Meunier, they reach an inn near the border -- which one isn't specified -- where, while Lange rests up, Valentine tells his story and leaves it up to the people at the inn whether they will turn him in. There's some famously show-offy camerawork from cinematographer Jean Bachelet, but the real energy of the film comes from Renoir's company of vivid, talkative characters, whose chatter and whose relationships unfold so rapidly that you may want to see the film twice to appreciate them. Le Crime de Monsieur Lange is second-tier Renoir but, with its genuine affection for human beings, it's better than most directors' top-tier work.

Watched on Filmstruck

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)

.jpg)